Following The 1% Podcast with the brilliant and funny Des Bishop, a background thought came to the foreground with further reflection. At the outset of the episode, we settled into our conversation by talking about how past errors or indiscretions helped position us toward a new course. In that regard, we can follow a negative trajectory downward, exacerbating what has gone wrong, or gain clarity and make necessary changes by understanding how and why certain events unfold against our desires or best-made plans.

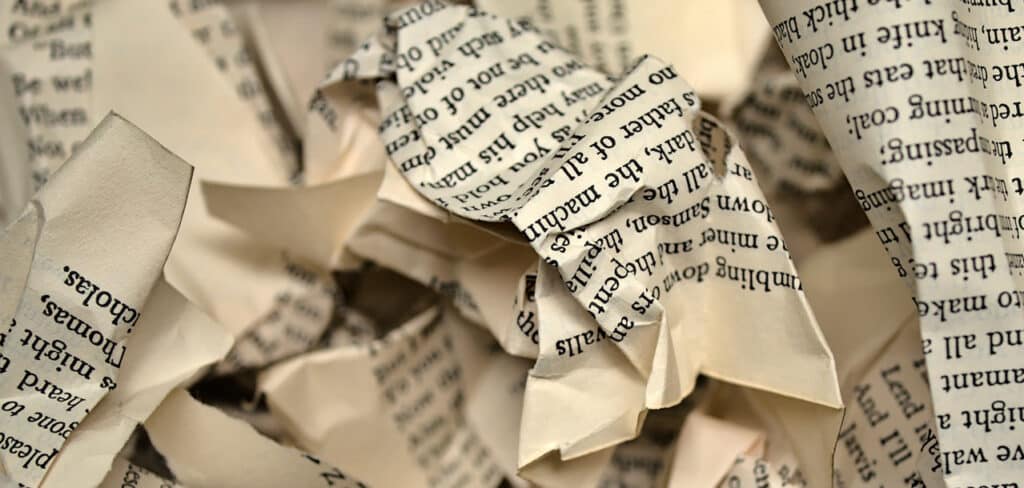

Making the most of your mistakes

Many know this but may not want to hear it. The concept may be anathema to your sense of being and thinking, and you may not even be willing to process the possibility in your workplace. Nevertheless, let’s talk about it. No matter how cautious, discerning, motivated, prepared, and skilled you are—failure is inevitable. So why does it happen, and why are we afraid of it?

Why we fail

Failure has many makers, and any of the causes below could prove costly. Yet, as a concept, it is something we should be less afraid of, if only because it is unavoidable and can aid us once we grapple with it. According to Shiv Khera, author of You Can Win (2014), we usually fail for one of seven reasons:

- Lack of persistence

- Lack of conviction

- Rationalisation

- Dismissal of past mistakes

- Lack of discipline

- Poor self-esteem

- A fatalistic attitude

Forbes magazine reiterates a lack of belief and expectation of sub-par outcomes and adds:

- The desire to not be disruptive even if required

- The instinct for self-preservation

- Losing sight of our agency

- Fear of risking what has been built and our legacy

- Real and imagined stagnation

- Confusion

Impatience, a lack of a clear plan, a missing long-term or contingent strategy, and poorly thought-out or unattainable objectives, can be included in the list.

Tuning in versus tuning out

Additionally, failure is frequently related to something happening in our lives. In other words, it is already within us and is a manifestation of an existing discomfort. Humans are complex entities, our psyches are even more layered and nebulous, and we are routinely impacted by unexpected and undesirable circumstances happening to us or around us. Moreover, the minutia of everyday life can easily influence all the causes above.

Therefore, to believe that unwanted aspects of our personal or professional lives can be wholly cordoned off from influencing job performance to some degree is naïve. That said, and as outlined in a previous 1% article, the ability to compartmentalise and conquer is necessary at certain moments, but what happens if and when we cannot do that entirely and are forced to face failure head-on?

Redirection through reappraisal

Random and not-so-random outcomes go against us or do not go according to expectations. Sometimes there is no logic for what has happened, at least in terms of the event itself. Befuddled as we are, we must act. In the corporate environment, often, there is little time or room for context.

What comes next—i.e., fixing it—requires consideration. Once we figure out how and why we can devise and execute a response. That does not simply mean carrying out damage control, although that, too, is a skill. Rather it entails an alteration of our mindset. We must reappraise the situation as well as ourselves. What was our role, if any, in this? What could have been done differently? What was learned, and how can we turn it into a gain? Mistakes can represent an opportunity, one specifically for change.

When we fail, we are highly conscious of the meaning of that setback and its repercussions. Our self-awareness is heightened, and we become more malleable and open-minded because we may be less sure of decisions or what is happening around us. Humans and markets are not always predictable or rational. However, these conditions help enact evolution and transformation, which are metonyms for progress. In that regard, failure precedes success.

Ad astra per aspera

You may know the meaning of the somewhat ambiguous, albeit ubiquitous, Latin phrase above (a rough road leads to the stars), but did you know that it adorns the memorial plaque for the astronauts who died on Apollo I? Not only is the phrase befitting, but its application to this tragic event is instructive.

On February 21, 1967, a cabin fire killed the three astronauts on board during a launch rehearsal. The mission had failed before it had even gotten off the ground. Rather than lose hope and stop, the American space programme looked inward and studied the series of mistakes that led to the accident in granular detail to learn from its errors. It saw fault within itself and did not attempt to shift blame or explain away the tragedy to either bad luck or the unknowable. Ultimately, NASA was better for it.

This shift was embodied by Gene Kranz, the legendary boss of Mission Control, who delivered this impassioned speech three days after the tragedy:

“Somewhere, somehow, we screwed up. Whatever it was, we should have caught it. We were too gung-ho about the schedule and we locked out all of the problems we saw each day in our work. […] From this day forward, Flight Control will be known by two words: ‘Tough’ and ‘Competent.’ Tough means we are forever accountable for what we do or what we fail to do. We will never again compromise our responsibilities. […] Competent means we will never take anything for granted. We will never be found short in our knowledge and in our skills. Mission Control will be perfect. When you leave this meeting today you will go to your office and the first thing you will do there is to write ‘Tough and Competent’ on your blackboards. It will never be erased.”

These words are known as the ‘Kranz Dictum,’ and they remain pillars of the programme. Surprisingly, Kranz’s 2009 book about the missions he was a part of is entitled, Failure Is Not An Option. Although inspiring, his title is a little misleading. Kranz, and everyone involved with Apollo I, failed. However, they were not defined by this and are instead remembered by their response. Two years later, the programme landed three men on the moon, one of the crowning achievements in the history of the human race.

Looking back, although NASA was interrupted by catastrophic failure to such a degree that it suspended crewed flights for twenty months, they were undeterred and used their mistakes as a catalyst for self-improvement. If we choose (and it is a choice) to use reflection, understanding, and growth as tools, every one of us can harness misfortune and miss-steps similarly.

More on Failure

Bouncing Back from Professional Failure

References

Khera, Shiv. You Can Win: A Step by Step Tool for Top Achievers. Bloomsbury India, 2014.

Kranz, Gene. Failure Is Not an Option: Mission Control From Mercury to Apollo 13 and Beyond. Simon & Schuster, 2009.