Introduction

Originally published in 2013, Ichiro Kishimi and Fumitake Koga’s The Courage to be Disliked quickly became a sensation in its authors’ native Japan. Its English language translation followed suit with more than 3.5 million copies sold worldwide.

The book is often shelved in the ‘self-help’ category, in large part due to its blandly overpromising subheading: How to free yourself, change your life and achieve real happiness. In truth it would be better suited to the philosophy or psychology section. The book takes the form of a discussion between a philosopher and an angsty student. The student is unhappy with his life and often with the philosopher himself, while the philosopher is a contented devotee of Adlerian psychology, the key points of which he disseminates to the student over the course of five neatly chunked conversations. His proposed principles offer sound advice for life in general but also prove useful when integrated into a business setting.

Adlerian Psychology

Alfred Adler was an Austrian born psychotherapist and one of the leading psychological minds of the 20th century. Originally a contemporary of Freud’s, the two soon drifted apart. In many ways Adler’s theories can be defined in opposition to his old contemporary; they are anti-Freudian at their core. Freud is a firm believer that our early experiences shape us. Adler is of the view that such sentiments strip us of autonomy in the here and now, seeing Freud’s ideas as a form of determinism. He instead proffers:

No experience is in itself a cause of our success or failure. We do not suffer from the shock of our experiences – the so-called trauma – but instead, we make out of them whatever suits our purposes. We are not determined by our experiences, but the meaning we give them is self-determining.

Essentially, then, the theories are reversed. Adler posits that rather than acting a certain way in the present because of something that happened in their past, people do what they do now because they chose to, and then use their past circumstances to justify the behaviour. Where Freud would make the case that a recluse doesn’t leave the house because of some traumatic childhood event, for example, Adler would argue that instead the recluse has made a decision to not leave the house (or even made it his goal not to do so) and is creating fear and anxiety in order to stay inside.

The argument comes down to aetiology vs teleology. More plainly, assessing something’s cause versus assessing its purpose. Using Adlerian theory, the philosopher in the book tells the student that: “At some stage in your life you chose to be unhappy, it’s not because you were born into unhappy circumstances or ended up in an unhappy situation, it’s that you judged the state of being unhappy to be good for you”. Adding, in line with what David Foster-Wallace referred to as the narcissism of self-loathing, that: “As long as one continues to use one’s misfortune to one’s advantage in order to be ‘special’, one will always need that misfortune.”

Adler in the workplace: teleology vs aetiology

An example of the difference in these theories in the workplace could be found by examining the sentence: “I cannot work to a high standard at this company because my boss isn’t supportive.” The viewpoint follows the cause and effect Freudian notion: your boss is not supportive therefore you cannot work well. What Adler, and in turn Kishimi and Koga, argue is that you still have a choice to make. You can work well without the support of your boss but are choosing to use their lack of support as an excuse to work poorly (which subconsciously was your aim all along).

This is the most controversial of Adler’s theories for a reason. Readers will no doubt look at the sentence and feel a prescription of blame being attributed to them. Anyone who has worked with a slovenly or uncaring boss might feel attacked and argue that their manager’s attitude most certainly did affect the quality of their work. But it’s worth embracing Adler’s view, even if just to disagree with it. Did you work as hard as you could and as well as you could under the circumstances? Or did knowing your boss was poor give you an excuse to grow slovenly too? Did it make you disinclined to give your best?

Another example in the book revolves around a young friend of the philosopher who dreams of becoming a novelist but never completes his work, citing that he’s too busy. The theory the philosopher offers is that the young writer wants to leave open the possibility that he could have been a novelist if he’d tried but he doesn’t want to face the reality that he might produce an inferior piece of writing and face rejection. Far easier to live in the realm of what could have been. He will continue making excuses until he dies because he does not want to allow for the possibility of failure that reality necessitates.

There are many people who don’t pursue careers along similar lines, staunch in the conviction that they could have thrived if only the opportunity had arisen without ever actively seeking that opportunity themselves. Even within a role it’s possible to shrug off this responsibility, saying that you’d have been better off working in X role in your company if only they had given you a shot, or that you’d be better off in a client-facing position rather than being sat behind a desk doing admin if only someone had spotted your skill sets and made use of them. But without asking for these things, without actively taking steps towards them, who does the responsibility lie with? It’s a hard truth, but a useful one to acknowledge.

Adler in the workplace: All problems are interpersonal relationship problems

Another of the key arguments in the book is that all problems are interpersonal relationship problems. What that means is that our every interaction is defined by the perception we have of ourselves versus the perception we have of whomever we are dealing with. Adler is the man who coined the term “inferiority complex”, and that factors into his thinking here. He spoke of two categories of inferiorities: objective and subjective. Objective inferiorities are things like being shorter than another person or having less money. Subjective inferiorities are those we create in our mind, and make up the vast majority. The good news is that “subjective interpretations can be altered as much as one likes…we are inhabitants of a subjective world.”

Adler is of the opinion that: “A healthy feeling of inferiority is not something that comes from comparing oneself to others; it comes from one’s comparison with one’s ideal self.” He speaks of the need to move from vertical relationships to horizontal ones. Vertical relationships are based in hierarchy. If you define your relationships vertically, you are constantly manoeuvring between interactions with those you deem above you and those you deem below you. When interacting with someone you deem above you on the hierarchical scale, you will automatically adjust your goalposts to be in line with their perceptions rather than defining success or failure on your own terms. As long as you are playing in their lane, you will always fall short. “When one is trying to be oneself, competition will inevitably get in the way.”

Of course in the workplace we do have hierarchical relationships. There are managers, there are mid-range workers, there are junior workers etc. The point is not to throw away these titles in pursuit of some newly communistic office environment. Rather it’s about attitude. If you are a boss, do you receive your underlings’ ideas as if they are your equal? Are you open to them? Or do you presume that your status as “above” automatically means anything they offer is “below”? Similarly if you are not the boss, are you trying to come up with the best ideas you can or the ones that you think will most be in-line with your boss’ pre-existing convictions? Obviously there’s a balance here – if you solely put forward wacky, irrelevant ideas that aren’t in line with your company’s ethos and have no chance of success then that’s probably not helpful, but within whatever tramlines your industry allows you can certainly get creative and trust your own taste rather than seeking to replicate someone else’s.

Pivotal to this is whether you are willing to be disagreed with and to disagree with others or are more interested in pleasing everyone, with no convictions of your own. This is where the book’s title stems from. As it notes, being disliked by someone “is proof that you are exercising your freedom and living in freedom, and a sign that you are living in accordance with your own principles…when you have gained that courage, your interpersonal relationships will all at once change into things of lightness.”

Adler in the workplace: The separation of tasks

The separation of tasks is pivotal to Adlerian theory and interpersonal relationships. It is how Adler, Kishimi and Koga suggest one avoids falling into the trap of defining oneself by another’s expectations. The question one must ask themselves at all times, they suggest, is: Whose task is this? We must focus solely on our own tasks, not letting anyone else alter them and not trying to alter anyone else’s. This is true for both literal tasks – a piece of work, for example – but also more abstract ideas. For example, how you dress is your task. What someone else thinks of how you dress is theirs. Do not make concessions to their notions (or your perceptions of what their notions might be) and do not be affected by what they think for it is not your task and therefore not yours to control.

This idea that we allow others to get on with their own tasks is crucial to Adler’s belief in how we can live rounded, fulfilling lives. The philosopher argues that the basis of our interpersonal relationships – and as such our own happiness – is confidence. When the boy asks how the philosopher defines the “confidence” of which he speaks, he answers:

It is doing without any set conditions whatsoever when believing in others. Even if one does not have sufficient objective grounds for trusting someone, one believes. One believes unconditionally without concerning oneself with such things as security. That is confidence.

This confidence is vital because the book’s ultimate theory is that community lies at the centre of everything. The awareness that “I am of use to someone” both allows one to act with confidence in their own life, have confidence in others, and to not be reliant on the praise of others. The reverse is true too. As Kishimi and Koga state, “A person who is obsessed with the desire for recognition does not have any community feeling yet, and has not managed to engage in self-acceptance, confidence in others, or contribution to others.” Once one possesses these things, the need for external recognition will naturally diminish.

For high-level employees, then, it’s important to set a tone in the workplace that allows colleagues to feel that they are of use. But as the book dictates, do not do this by fake praise – all that will do is foster further need for recognition (“Being praised essentially means that one is receiving judgement from another person as ‘good.’”) Instead, foster this atmosphere by trusting them, showing confidence.

The courage to be disliked

The Courage to be Disliked is at odds with many of the accepted wisdoms of the day. Modern cultural milieu suggests that we should be at all times accepting and validating others’ trauma as well as our own. Many may even find solace in this approach and find that it suits them best. But there is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to fostering a successful workplace and even less so when it comes to leading a fulfilling life. For anyone who feels confined by the idea that there are parameters around what they can achieve and are capable of because of some past event or some subjective inferiority that has been harboured too long, perhaps look at those interpersonal relationships, perhaps find the courage to be disliked, and in doing so hope to find a community that you’re willing to support as much as it supports you. There is no need to be shackled to whatever mythos you’ve internally created.

As the book states: “Your life is not something that someone gives you, but something you choose yourself, and you are the one who decides how you live…No matter what has occurred in your life up to this point, it should have no bearing at all on how you live from now on.”

References

Kishimi, Ichiro & Koga, Fumitake. The Courage to Be Disliked: How to Free Yourself, Change your Life and Achieve Real Happiness. Bolinda Publishing Pty Ltd. 2013.

Introduction

Consider a simple yet profound question: What does your work mean to you? Is it merely a task to be completed, or does it resonate with a deeper purpose in your life?

Viktor Frankl, a prominent Austrian psychiatrist and philosopher, grappled with these very questions, evolving them into a broader exploration of life’s meaning. Drawing from his harrowing experiences in Nazi concentration camps, he developed logotherapy—a form of psychotherapy that centres around the search for meaning and purpose. Through logotherapy, Frankl illuminated the idea that life’s essence can be found not just in joyous moments but also in love, work, and our attitude towards inevitable suffering. This pioneering approach underscores personal responsibility and has offered countless individuals a renewed perspective on fulfilment, even in the face of daunting challenges.

In this piece, we delve into the intricacies of Frankl’s teachings, exploring the symbiotic relationship he identified between work and our quest for meaning.

A Holistic Approach to Life and Work

In his seminal work, ‘Man’s Search for Meaning,’ Viktor Frankl delved deeply into the multifaceted nature of human existence. He eloquently described the myriad pathways through which individuals uncover meaning. For Frankl, while work or ‘doing’ is undoubtedly a significant avenue for deriving meaning, it isn’t the only one. He emphasised the value of love, relationships, and our responses to inevitable suffering. Through this lens, he offered a panoramic view of life, advocating for a holistic perspective where meaning is not strictly tethered to our work but is intricately woven through all our experiences and interactions.

Progressing in his exploration, Frankl sounded a note of caution about the perils of letting work become an all-consuming end in itself. He drew attention to the risks of burnout and existential exhaustion when one’s sense of purpose is confined solely to one’s occupation or the relentless chase for wealth. To Frankl, an overemphasis on materialistic achievements could inadvertently lead individuals into what he termed an ‘existential vacuum’ – a state where life seems starkly devoid of purpose. He argued that in our quest for success, we must continually seek a deeper, more intrinsic purpose. Otherwise, we risk being blinded by life’s profound significance and richness beyond material gains.

Delving deeper into the realm of employment, Frankl confronted the psychological and existential challenges of unemployment. He noted that without the inherent structure and purpose provided by work, many individuals grapple with a profound sense of meaninglessness. This emotional and existential void often manifests in a diminishing sense of significance towards time, leading to dwindling motivation to engage wholeheartedly with the world. The ‘existential vacuum’ emerges again, casting its shadow and enveloping individuals in feelings of purposelessness.

Yet, Frankl’s observations were not merely confined to the challenges. He beautifully illuminated the resilience and fortitude of certain individuals, even in the face of unemployment. He showcased how, instead of linking paid work directly with purpose, some found profound meaning in alternative avenues such as volunteer work, creative arts, education, and community participation.

Frankl firmly believed that the essence of life’s meaning often lies outside the traditional realms of employment. To drive home this perspective, he recounted poignant stories, such as that of a desolate young man who unearthed profound purpose and reaffirmed his belief in his intrinsic value by preventing a distressed girl from taking her life. Such acts, as illustrated by Frankl, highlight the boundless potential for a meaningful existence, often discovered in genuine moments of human connection.

Work as an Avenue for Meaning and Identity

Viktor Frankl’s discourse on work transcended the common notions of duty and obligation. For him, work was more than a mere means to an end; it was a potent avenue to unearth meaning and articulate one’s identity. Frankl posited that when individuals align their work with their intrinsic identity—encompassing all its nuances and dimensions—they move beyond merely working to make a living. Instead, they find themselves working with a purpose.

This profound idea stems from his unwavering belief that our work provides us with a unique opportunity. Through it, we can harness our individual strengths and talents, channelling them to create a meaningful and lasting impact on the world around us.

In line with modern philosophical thought, which views work as a primary canvas for self-expression and self-realisation, Frankl also recognised its significance. He believed that work could serve as a pure channel, finely tuned to our unique skills, passions, and aspirations. This deep sense of accomplishment and fulfilment from one’s chosen profession, he asserted, is invaluable. However, Frankl also emphasised the importance of seeing the broader picture. While careers undeniably play a significant role in our lives, they are but a single facet in our ongoing quest for meaning.

Frankl reminds us that while our careers are integral to our lives, the quest for meaning isn’t imprisoned within their boundaries. He believed the core of true meaning emerges from our deep relationships, our natural capacity for empathy, and our virtues. These treasures of life, he asserted, can be manifested both within the confines of our workplace and beyond.

The True Measure of Meaning Through Work

For Viktor Frankl, our professional lives brim with potential for fulfilment. Yet, fulfilment wasn’t solely defined by accolades. Instead, it was about aligning our work with our deepest values and desires. It wasn’t just the milestones that mattered but how they resonated with our core beliefs.

Frankl’s logotherapy reshapes our perception of work, emphasising that even mundane tasks can hold significance when approached with intent. With the right mindset, every job becomes a step in our journey for meaning.

In Frankl’s writings, he weaves together tales of profound significance—a young man’s transformative act of kindness, a narrative not strictly tethered to work’s traditional realm. Yet, these stories anchor a timeless truth: In every endeavour, whether grand or humble, lies the potential for unparalleled meaning. Here, work isn’t just about designated roles—it becomes an evocative stage where profound moments play out. Beyond job titles and tasks, the depth, sincerity, and fervour we infuse into each act truly capture the essence of meaningful work.

Finding Fulfilment in Every Facet

Viktor Frankl’s profound insights into the human pursuit of meaning provide a distinctive lens through which we can evaluate both our daily tasks and life’s most pivotal moments. Through his exploration—whether addressing the ordinariness of daily life or the extremities of crisis—Frankl illuminated the profound interconnectedness of work and personal identity. He posited that our professions, while significant, are fragments of a vast tapestry that constitute human existence.

Navigating the journey of life requires continual adjustments to our perceptions of success and meaning. While our careers and professional achievements are significant, true fulfilment goes beyond these confines. It’s woven into our human experiences, the bonds we nurture, the challenges we face, and the joys we hold dear.

Frankl’s pioneering work in logotherapy urges us to approach life with intention and purpose. He beckons us to see the value in every moment, task, and human connection. As we delve into our careers and strive for success, aligning not just with outward accomplishments but with the very essence of who we are is vital.

Introduction

It’s not who you are underneath, it’s what you do that defines you. Batman said it so it must be true. (Technically it was said to him first then made a running motif of the film’s core theme, but we may be splitting hairs.)

What we do does define us. Look no further than the first question directed your way by any small talk specialist at a party: what do you do? The question has a more pronounced meaning than simply what is your career. It’s designed to get a sense of what that profession says about you – your class, education, status, salary.

The most popular surname in Germany and Switzerland is Müller, meaning miller. In Slovakia, it’s Varga, the word for cobbler. In the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the US, it’s Smith, due to the word’s attachment to a variety of once common trades such as blacksmith and locksmith [1]. Your work, then, used to be your literal identity.

In purely nominative terms, that has changed. We do not live amongst Wayne Footballer, Elon Disruptor or Donald Moron. But in terms of social function, our profession is still the definitive modus of identification, at least on first glance. In today’s world, unlike in Batman’s, our job is both what we do and indicative of who we are underneath.

Work as identity

The vast majority of people spend the bulk of their waking hours at work. That was true pre-pandemic when office work practices were the norm. Home and hybrid working have changed things somewhat. There is more flexibility to work schedules, but that does not detract from the amount of our time given to work. In fact, the ability to do our jobs from home has in many cases seen work spill over into what was once free time. Anne Wilson, a professor of psychology at Wilfrid Laurier University in Ontario, terms the psychological state that accompanies investing a disproportionate amount of time and energy to work as “enmeshment” [2].

Wilson found that workers with greater autonomy over their schedule – such as those in high-powered executive positions, lawyers, entrepreneurs and academics – were most affected by enmeshment. However, with greater autonomy over scheduling and certainly location now afforded to the many workers across the world, enmeshment’s prevalence is only growing.

What do you mean?

Given the prominent role our career plays in how we either identify ourselves or are identified by others, it makes sense that we want our work to provide meaning. After all, if work takes up most of your time and is seen as a solid representative indicator of who you are, then having a meaningful job surely necessitates that you also lead a meaningful life.

Meaning has the highest impact on whether an employee chooses to stay at their job or move on [3]. In fact, employees who derive meaning from their work are more than three times as likely to stay with their organisations [4]. On top of that, employees who consider their work to have meaning report 1.7 times higher job satisfaction and are 1.4 times more engaged with their work [5]. Meaning, it seems safe to say then, is good.

And yet a 2017 report from Gallup found that just 13% of the world’s workforce felt “engaged” at work [6]. Gallup defines unengaged workers as those who are “checked out” from their work, distinguishing between unengaged workers and those who are actively disengaged. This latter group, “act out on their unhappiness, take up more of their managers’ time and undermine what their co-workers accomplish” [7].

According to a separate Gallup study from 2013, actively disengaged workers cost US companies a whopping $450 billion to $550 billion per year [8]. In other words, for any cynical employers reading this who think their workers’ pursuit of meaning is nothing more than a tiresome display of existential narcissism that falls outside their professional remit, think again. Meaning is money. Meaning is business. And your staff’s search for meaning is your business.

A map to meaning

Positive Psychology lays out the most prominent job satisfaction theories. There’s Edwin Locke’s range of affect theory, predicated on the importance of meeting expectations. If employee A wants a team-oriented work culture, for example, offering one will provide them job satisfaction, and vice versa.

Then there is the dispositional approach, which posits that while our job satisfaction may fluctuate slightly according to our specific workplace circumstances, more important than whatever workplace culture we’re currently part of is our natural disposition. People with high self-esteem, high levels of self-efficacy, and/or low levels of neuroticism are more likely to be satisfied in their job than those of the opposite disposition, irrespective of whether the job caters to their specific needs or not.

The Job Characteristics Model argues that workplace satisfaction is contingent on factors such as skill variety, task significance, autonomy and feedback. While Equity theory posits that satisfaction depends on a trade-off between input and output. The level or hard work required, enthusiasm for the job and support of or for colleagues is being constantly evaluated against the financial compensation, feedback from higher-ups and job security the role offers, for example.

No theory is fully complete but all offer windows into what satisfaction supposedly looks like – with a great deal of crossover. Essentially a job that does all of or some of the following will prove satisfying: meets employee needs, offers work that is appropriately challenging, gives staff a decent level of control, provides a positive atmosphere (generally best obtained through co-worker collaboration and feedback from senior figures.). None of that, we’re sure you’ll agree, is groundbreaking information. As solutions, they’re easily identified, but harder to put into practice.

Tangible options

A practice often associated with job satisfaction is that of job crafting. For a deep dive on what crafting entails, read our article on the subject here. In short, it involves redefining the way you work, adjusting your role so that it better aligns with your specific skill sets. Sculpting a more personalised version of your position helps you – and in turn, the business – thrive, while simultaneously helping you derive meaning as you’re less likely to feel that your unique strengths are going to waste.

In accordance with the pursuit of meaning, psychologists Claudia Harzer and Willibald Ruch acknowledged the significance of finding a “calling” [9]. While many professionals may not end up working in the sphere of what they consider to be their calling, through crafting they can help bring their would-be calling to their existing role.

Another tangible step one can take to ensure they obtain a sense of meaning from their work is to prioritise relationships. Aaron Hurst, founder of Imperative and the Taproot Foundation and the author of The Purpose Economy, notes that his 20 years of research into the subject of workplace fulfilment found relationships to be, “the leading driver of meaning and fulfilment at work. If you lack relationships, it’s almost impossible to be fulfilled at work or life in general” [10].

Hurst’s definition of meaningful work revolves around three core questions. Do you feel like: (a) You’re making an impact that matters? (b) You have meaningful relationships? (c) You’re growing? If the answer to all three is yes, meaning will surely follow.

Assigning meaning

Of course, we all ascribe meaning to different priorities based on our outlook, upbringing, and social and fiscal circumstances, amongst other factors. As Douglas Lepisto and Camille Pradies describe in their 2013 book Purpose and Meaning in the Workplace, some people “may derive meaning not from the job itself, but from the fact that it allows them to provide for their families and pursue non-work activities that they enjoy” [11].

As noted earlier, some professions feel less like work and more like a calling. Researchers have found that those in jobs they consider their calling are amongst the most content [12]. One of the examples they give is that of zookeepers, noting that “though more than eight in 10 zookeepers have college degrees, their average annual income is less than $25,000.” On top of that, “there’s little room for advancement and zookeepers tend not to be held in high regard” [13]. Despite the relatively limited fiscal reward and few opportunities for growth, job satisfaction among zookeepers is strikingly high. That’s because many of them are doing a job that they deem to be their purpose.

Not only that, but to follow on from Hurst’s point regarding relationships, zookeepers were found to also feel that their co-workers experienced the same motivation and sense of duty they did, helping them form closer bonds. “It’s not just that you do the same work, but you’re the same kind of people,” explains Stuart Bunderson, PhD, a professor of organisational behaviour at the Olin Business School at Washington University. “It gives you a connection to a community” [14].

Approach

We’ve already looked at the dispositional theory around job satisfaction, which contends that our natural outlook has more bearing on our sense of purpose or satisfaction than the scope of the role itself. But we don’t all need to be shiny, happy people (as R.E.M. would put it) to find meaning in our work.

Michael G. Pratt, PhD, a professor of management and organisation at Boston College, demonstrates the variables of approaches we can adopt by relaying a tale of three bricklayers hard at work.

When asked what they’re doing, the first bricklayer responds, “I’m putting one brick on top of another.” The second replies, “I’m making six pence an hour.” And the third says, “I’m building a cathedral — a house of God.” [15]

“All of them have created meaning out of what they’ve done,” Pratt says, “but the last person could say what he’s done is meaningful. Meaningfulness is about the why, not just about what” [16]. Perhaps that’s why a 2013 Gallup report found that “employees with college degrees are less likely than those with less education to report being engaged in their work — even though a college degree leads to higher lifetime earnings, on average” [17]. They’re earning more money, sure. But they’re not scratching that vocational itch.

We’ve already written about the professional benefits associated with adopting a positive mindset here. A notable finding is the way that our approaches – both positive and negative – can land us in a feedback loop of sorts. A 2021 study in the European Journal of Personality investigating the relationship between self-esteem and work experiences found that, “The overall reciprocal pattern between work experiences and self-esteem is in line with the corresponsive principle of neo-socioanalytic theory, stating that life experiences deepen those personality characteristics that have led to the experiences in the first place” [18].

Put more simply:

an individual with high self-esteem tends to experience more job satisfaction, and experiencing job satisfaction positively affects the individual’s self-esteem. Thus, the reciprocal effects imply a positive feedback loop for people with high self-esteem and favorable work experiences and, at the same time, a vicious circle for people with low self-esteem and unfavorable work experiences. [19]

In your hands

A 2018 PwC/CECP study found that a remarkable 96% of employees believe that achieving fulfilment at work is possible, with 70% saying they’d consider leaving their current role for a more fulfilling one [20]. One in three even said they’d take a pay cut if necessary. Meanwhile 82% considered deriving meaning from work to be primarily their own responsibility, with 42% saying that they were their own greatest barrier to finding fulfilment at work [21].

There’s no one size fits all solution for finding meaning at work, but adopting a positive approach, building genuine workplace relationships, chasing your “calling”, or crafting your existing role so that it better aligns with your unique strengths and interests are all techniques worth exploring.

References

[1] https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20210409-why-we-define-ourselves-by-our-jobs

[2] https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20210409-why-we-define-ourselves-by-our-jobs

[3] https://www.fastcompany.com/3032126/how-to-find-meaning-during-your-pursuit-of-happiness-at-work

[4] https://www.fastcompany.com/3032126/how-to-find-meaning-during-your-pursuit-of-happiness-at-work

[5] https://www.fastcompany.com/3032126/how-to-find-meaning-during-your-pursuit-of-happiness-at-work

[6] https://positivepsychology.com/job-satisfaction-theory/

[7] https://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/12/job-satisfaction

[8] https://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/12/job-satisfaction

[9] https://positivepsychology.com/job-satisfaction-theory/

[11] https://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/12/job-satisfaction

[10] https://bigthink.com/the-learning-curve/finding-fulfillment-at-work/

[12] https://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/12/job-satisfaction

[13] https://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/12/job-satisfaction

[14] https://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/12/job-satisfaction

[15] https://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/12/job-satisfaction

[16] https://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/12/job-satisfaction

[17] https://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/12/job-satisfaction

[18] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/08902070211027142

[19] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/08902070211027142

Job satisfaction is something we all strive for but by no means all attain. There are various reasons for us to slip into feelings of apathy around our work. We may feel that we are being overlooked and that our skillsets are not being put to good use; we may feel that we are overworked and burnt out or maybe overwhelmed with stress; perhaps a lack of proper work-life balance is impacting our relationship with our friends and family; maybe we don’t fit in with our colleagues or are not contributing as effectively as those around us; or perhaps we even feel that we followed the wrong career path altogether – that the rung of the ladder is less of the issue than the ladder itself. Dissatisfaction is likely to come to all workers at some point. Oftentimes it passes, proving itself to be no more than a tough project or bad day at the office. But if the problem is consistent and/or stifling, action may need to be taken. For those who don’t think the job itself is the problem so much as how they’re handling it, a potential solution is work crafting.

What is work crafting?

Tims et al. (2012)1 define crafting as “the changes employees may make to balance their job demands and job resources with their personal abilities and needs.” The ultimate aim of doing this is to inject work with greater meaning and make it more engaging2. Essentially, without changing our job in any tangible sense – title, deliverables etc. – we ‘craft’ a new, more personalised version of our existing role to make it one that we can better love and thrive in, one “where we still can satisfy and excel in our functions, but which is simultaneously more aligned with our strengths, motives, and passions.”3

Employers may be reading that and biting their nails, but fear not, job crafting is not a license for employees to entirely reconstruct their role, ignoring the aspects of their job they find tedious and unrewarding and replacing them with exclusively grand and shiny tasks that provoke feelings of fulfilment. While management of tasks does factor into work crafting, the more important aspect is based around meaning. As argued by Berg et al. (2008)4, “job crafting theory does not devalue the importance of job designs assigned by managers; it simply values the opportunities employees have to change them.”

Job crafting vs Job design

The CIPD define job design as, “the process of establishing employees’ roles and responsibilities and the systems and procedures that they should use or follow.”5 Its purpose revolves around optimising processes in the workplace to create value and maximise performance. So far, so similar to job crafting. The key difference between the two lies in who is doing the decision-making.

In job design, an employer will be setting boundaries and assigning tasks based on their best understanding of their employees, making a conscious effort to give them work that will reward them and suit their skillsets. In job crafting, it is employees taking the reins. Workers are proactive, and the approach places their wellbeing front and centre. Again, that may be ground that employers are nervous to cede, but job crafting has been linked to better performance, motivation, and employee engagement6.

The three key forms of job crafting

There are various (and varying) approaches to job crafting, but three approaches are most common.

- Task crafting

This is the aspect we have focused on so far, with employees taking a more hands-on approach to their workloads. That could refer to work location (opting to work from home or on a hybrid basis, for example), time management (choosing hours that better suit their life commitments or generally working outside of a traditional 9-5 timeframe), or the tasks themselves (adding or removing tasks from their workload).

The examples around location and working hours are increasingly uncontroversial, especially in the wake of the pandemic. It is the third (employees selecting which tasks they wish to take on) that is the most divisive. Though it should be noted that generally task crafting involves taking on additional tasks rather than removing others. For example, a chef may take it upon themselves to not just serve food but to create aesthetically pleasing plates that enhance a customer’s dining experience. Or a bus driver might decide to give helpful sightseeing advice to tourists along his route7. Potentially an employee working in an administrative capacity may wish to become more engaged with the business, so learn a new software or sales technique, or become more actively involved with clients.

- Relationship crafting

Relationship crafting, unsurprisingly, is all about relationships. Primarily, relationships in the workplace. Having poor interpersonal relationships with colleagues has been found to be a significant contributor to workplace stress8. Conversely, positive work relationships are shown to increase job satisfaction, as well as general mood. By taking a more enthusiastic approach to workplace relationships, whether in or out of office hours, employees are thought to become more engaged with the company and feel more fulfilled in their role.

- Cognitive crafting

Cognitive crafting is all about how we frame the work we do. By assigning meaning to tasks that were conceivably uninspiring or outright deflating before, we can reshape our outlook, instilling our work and lives with a greater sense of purpose, and thus fulfilment. For example, a maid reframing the idea of changing a hotel guest’s bedsheets from a chore to a way to improve someone else’s holiday. Or a customer service worker approaching their clients’ problems like they were a therapist, looking to genuinely make their life better. Framing work tasks in a more positive manner can make work a far more enriching experience, and, unsurprisingly, removing any self-made narratives that what we’re doing is pointless improves mood no end.

Autonomy

The overarching benefit of crafting is the autonomy it affords employees. By giving workers control over how they spend and approach their time, they are able to feel a sense of achievement that might otherwise be lacking. And achievement breeds motivation for more, not to mention the added confidence and sense of worth it affords. A study by Steelcase9 found that when people have greater control over their experiences in the workplace, they become more engaged, which naturally results in greater performance.

Tellingly, studies on the happiness of women in the workplace10 found that there was no difference in mood across participants who worked full-time, part-time or didn’t work at all. Instead, the correlation between the women who were happiest was that they were the ones able to choose their work hours and professions. People have no problem committing to hard work, so long as it’s of their own volition, or offering them a benefit in return, even or especially if that benefit is solely personal fulfilment. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Barbara Ehrenreich, in her book Nickel and Dimed11, found that workers who had little control over the schedules found it disempowering and disabling.

Conclusion

Work-life balance is oft-discussed, and understandably so. We want to be able to enjoy our lives outside of work. This is arguably more important (and harder) now than ever as the lines continue to blur between our homes and workplaces, and our personal and professional devices. Less discussed is how we imbue our work lives with value. A healthy work-life balance should not entail misery during work hours and blissful respite when free. Rather, we should take steps to ensure that our professional days are filled with rewarding moments, whether that be because we’re performing tasks we want to be performing, framing our actions in a healthy, self-loving way, or performing those tasks with people that make it all worthwhile.

Crafting, whether of the task, relationship, or cognitive variety, offers us a way to feel more engaged and fulfilled, to improve our performance, and to take strides towards achieving professional goals we want to conquer. Lost for meaning in your professional life? Give crafting a try.

References

1 Tims, M., Bakker, A., and Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 173–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

2 https://hbr.org/2020/03/what-job-crafting-looks-like

3 Wrzesniewski, A., Berg, J. M., & Dutton, J. E. (2010). Turn the job you have into the job you

want. Harvard Business Review, June, 114-117.

4 Berg, Justin M., et al. “What Is Job Crafting and Why Does It Matter.” Retrieved Form the Website of Positive Organizational Scholarship on April, vol. 15, 2008, p. 2011.

5 https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/strategy/organisational-development/job-design-factsheet#gref

6 https://positivepsychology.com/job-crafting/

7 https://positivepsychology.com/job-crafting/

8 https://positivepsychology.com/positive-relationships-workplace/

9 https://info.steelcase.com/global-employee-engagement-workplace-comparison#key-finding-2

11 APA. Ehrenreich, B. (2010). Nickel and dimed. Granta Books.

A modish topic, but sometimes less emphasised, facet of success is company culture. Culture is a catchall term, but it comes down to how organisation systems are formed and maintained. It is social in origin and totalising in dissemination. That matters because humans are not innate; we produce and reproduce these systems through learned behaviour, mirroring, and various institutions. Our institutionality may be the most significant in this regard and comprises hierarchal and horizontal models within which mores, norms and values spread. Whether through family, friends, school, religion, creative arts, hobbies, sports, government, society, or work, we spend most of our lives practising and passing on culture.

A parallax view

Defining company culture (also known as corporate or organisational culture) can be equally ambiguous. According to the Harvard Business Review, culture encompasses an entity’s collective attitudes, beliefs, logic, mission, ethics and values, plus the actions and behaviours that result. Because companies tend to function from the top down—i.e., from superiors to subordinates—company culture should equally emphasise how employees relate to the above.

At the executive level, culture leans toward leadership style, management and order. Although these facets relate directly to company culture, they have more to do with the structure of the entity rather than its employees. Shifting the view from bottom to top makes it possible to locate unseen or underutilised areas for improvement. This perspective emphasises an entity’s ‘feel’ and ‘philosophy.’ As a phenomenon, parallax is the change in an object’s position due to a change in the observer’s line of sight. Since we are using this term conceptually, it is a gap that may appear between strategic design and unexamined effects when altering the angle of observation.

To ascertain and harness what are, in essence, intangibles, we must therefore understand that company culture is potentially a limitless category. It entails compensation and safety, first and foremost. However, other factors include buy-in, intensity, morale, professionalism, the physical space, and employees’ responses to their quotidian conditions and your core principles.

Management’s ability to check the ‘temperature of the room’ and its reflexivity is essential. Every employee (to some degree) impacts functionality, planning, and overall performance. What is more, many intangible qualities do have material effects. For instance, research shows that companies with high-pressure work environments spend up to 50% more on health care than other organisations. We are talking about people as well as the bottom line.

Ecologies of communication

Company Culture is rooted in its social ecosystems and transmitted vis-à-vis the organisation and practices of a workplace. Every dialogical and structural component—e.g., discourse, the frequency and quality of communication, the chain of command, incentives, sanctions, etc.—augments or detracts from a sense of value. The refrain, ‘am I valued,’ is at the heart of many conversations, and employees communicate with each other directly and indirectly throughout the day. They communicate with clients and customers even more. What underpins these conversations—ultimately, meaning.

Operationally, company culture is ‘how tasks are executed’ and ‘how a workplace is managed.’ Meaning, however, has more to do with ‘how a workplace self-manages,’ which reflects the employees’ experiences, and ‘how management’s actions and ideals are received below.’ Critically, the former has much to do with a belief in the task at hand, that this or this role is vital, and the latter is affected by their experience by seeing things in practice, not just hearing them in rhetoric.

Company culture is felt most acutely at the bottom and may be sensed even by those outside a company’s walls. Clients and customers can also check the dial. To map or measure culture requires then formal and informal metrics. Besides reading the numbers, which can conceal certain aspects, the most direct way to get a feel for the workplace experience is to ask the employees themselves. Surveys can be a highly effective tool if written well and delivered in a way that communicates this is a priority.

Do not be fooled by shortcuts or rely only on incentives. Perks like extra vacation time do not matter if it entails burnout. Look at things long-term. Innovative policies that expand points of teamwork can create camaraderie. While offering merit-based leadership opportunities promotes ownership. These experiential elements contribute directly to company culture and help concretise a healthier workplace. There is no substitute for employees who believes in what they are doing, which begins during the hiring process, or their positive daily experience after that. If this criterion is missing, they must believe that change is possible. That belief comes from above.

Interpreting the numbers

Company culture affects performance on metrics such as finances, retention, innovation and customer service. Data compiled by Great Place To Work and FTSE Russell distills that the annual returns for the Fortune 100 Best Companies to Work For have made a cumulative return of 1,709% since 1998, compared to a 526% return for the Russell 3000 Index. The ‘100 Best index’ outperformed the broader market by 16.5%, returning 37.4% compared to a 20.9% return for the Russell 3000 Index in 2020.

Gallup polls indicate that only 34% (and falling) of American workers are actively engaged with their work, a part of a longer decline since Covid. It seems unwise to assume that such levels of disengagement would not translate to client experience or customer service. It does. Related polls predict that customer slumps are likely to represent the next turn in a cycle defined by a record number of resignations and vacancies.

Among younger generations, retention figures centre around three key predictors: an organisation’s reputation, a sense of purpose, and a connection to one’s job. Further research by Great Place to Work reveals that Millennials are eleven times more likely to leave a company than Gen Xers if their needs are not met. Currently, those needs relate to wider experience and meaning. People want to be valued and feel engaged with what they are doing and, reciprocally, value wealth and lifestyle less enthusiastically.

Help your team stay invested in what they are doing. To this end, inclusive leadership behaviours and systems, enlarged platforms for sharing ideas, and receptiveness to change communicates meaning and engender a sense of ownership in what is at stake. Refrain from equating dissatisfaction purely with a lack of material gains. Although this Deloitte survey imparts that 94% of executives and 88% of employees believe that company culture is decisive for success, there was a noticeable deviation regarding what factors are most important. Financial performance and competitive compensation took precedence at the executive level, but these were the poorest scoring factors below. For those looking up, healthy or candid communication, recognition, and access to leadership/management scored highest. What can we infer from this data? Feel matters. Philosophy matters. Possibility matters.

Conclusion

Company culture is the personality of a workplace. It is what someone would say regarding what it is like to work here, not in principle, but in actuality. That has lots to do with consistency and norms, but do not lose sight of the role of ethics and values. An organisation’s chief asset is talent. Constantly reiterate purpose and recognise people through company culture.

Remember, culture is shared. Employees who do not believe in what they or those above them are doing, who do not think that they—and not just their performance—matters, or worse, that they are locked into an unchanging situation have a hidden drag effect. The usual metrics do not easily show what potential productivity looks like under the right conditions. They show what is there, not what is possible. To that end, company culture, in particular, is prone to misinterpretation. It is not just about what is there. Equally, it is about what is missing. Find ways to gauge the situation as it stands and foster conditions that are more beneficial on a professional and personal basis.

Looking beyond the numbers, in Conscious Capitalism (2013), John Mackey, a cofounder of Whole Foods, and Raj Sisodia of Babson College point out that purpose-based workplaces are on the rise in the corporate world and society at large because they generate productivity as well as because customers increasingly gravitate to them. If all stakeholders matter, a company that values its employees is more likely to value its customers. Thus, meaning translates to inside performance as well as outside pull.

In The Story of Philosophy, Will Durant (1926/1991: 98) intuits from the work of Aristotle, ‘we are what we repeatedly do.’ If his postulate is correct, and I believe it is, should that not have meaning? We can think of company culture similarly. We spend much of our lives at work. For that time to feel like a journey rather than a grind, our environment should feel responsive to our needs. Above all else, what you are doing has to have meaning.

References

Azagba, Sunday, and Mesbah F. Sharaf. “Psychosocial Working Conditions and the Utilization of Health Care Services.” BMC Public Health, vol. 11, no. 1, Aug. 2011, p. 642, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-642.

Deloitte. Core Beliefs and Culture: Chairman’s Survey Findings. 2012, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/About-Deloitte/gx-core-beliefs-and-culture.pdf.

Durant, Will. The Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the World’s Greatest Philosophers. Pocket Books, 1991.

Gallup. “Is a Great Customer Resignation Next?” Gallup.Com, 20 May 2022, https://www.gallup.com/workplace/392537/great-customer-resignation-next.aspx.

—. “The ‘Great Resignation’ Is Really the ‘Great Discontent.’” Gallup.Com, 22 July 2021, https://www.gallup.com/workplace/351545/great-resignation-really-great-discontent.aspx.

Great Place to Work. Best Companies to Work For – Top Workplaces in the US | Great Place To Work. https://www.greatplacetowork.com/best-companies-to-work-for.

Hastwell, Claire. “The 3 Biggest Predictors of Employee Retention (Especially Millennials).” Great Place To Work®, https://www.greatplacetowork.com/resources/blog/3-keys-to-millennial-employee-retention?utm_campaign=2021.08.seo&utm_medium=blog&utm_source=gptw-website&utm_content=text-link&utm_term=80943&utm_audience=prospect.

Mackey, John, and Rajendra Sisodia. Conscious Capitalism: Liberating the Heroic Spirit of Business. Harvard Business Press, 2012.

Seppälä, Emma, and Kim Cameron. “Proof That Positive Work Cultures Are More Productive.” Harvard Business Review, 1 Dec. 2015, https://hbr.org/2015/12/proof-that-positive-work-cultures-are-more-productive.

Watkins, Michael D. “What Is Organizational Culture? And Why Should We Care?” Harvard Business Review, 15 May 2013, https://hbr.org/2013/05/what-is-organizational-culture.

Yoshimoto, Catherine, and Marcus Erb. “Treating Employees Well Led to Higher Stock Prices During the Pandemic.” Great Place To Work®, 5 Aug. 2001, https://www.greatplacetowork.com/resources/blog/treating-employees-well-led-to-higher-stock-prices-during-the-pandemic?utm_campaign=2021.08.seo&utm_medium=blog&utm_source=gptw-website&utm_content=text-link&utm_term=80943&utm_audience=prospect.

As the age-old saying goes, ‘If you love what you do, you never work a day in your life’. But how true is it? For most people, loving what you do comes at a cost. And loving what you do may not be as fulfilling as you’re led to believe.

It is natural for humans to search for meaning in their careers, especially when most of the waking day is spent at work. In fact, the average person spends 90,000 hours at work over a lifetime, which is one-third of a life. That is a lot of time that could either be soul-fuelling or soul-destroying. However, building a life that you love involves more than simply enjoying your day job. For some, benefits, stability, and the ability to spend time with loved ones and shut off at the end of the day are far more rewarding than loving the work itself.

Should you quit your job to pursue your dreams? You might want to consider what it means before jet-setting across the world.

Where did the idea of ‘loving the work you do’ originate?

Sarah Jaffe, author of Work Won’t Love You Back: How Devotion to Our Jobs Keeps Us Exploited, explains how the slogan, ‘If you love what you do, you never work a day in your life’ originated from a time when women were expected to do unpaid labour in the domestic space under the guise that it is ‘natural’ for women to enjoy this type of work. In creative pursuits, artists were underpaid or not paid at all because their work was seen as their passion and therefore, the reward was in the making.

‘Loving the work you do’ was a way to exploit workers, and it still is. Many creative jobs do not pay well. It may be appealing to quit your 9-5 in the hopes of living the digital nomad lifestyle, but the reality is often much bleaker than it appears. For entrepreneurs, the idea of starting a business may appeal for similar reasons — flexible working hours, control over one’s own time, passion, and potential to earn more — but those benefits often do not come until years later.

Why doing what you love doesn’t always pan out

It can be exciting to take the leap and pursue your passion, but managing expectations is essential. First, doing what you love may require sacrifices in other areas of life. This may mean working longer hours, working on weekends, and accepting little to no monetary reward at the outset. Further, research shows that 60% of businesses fail in the first three years. If your dream is to be your own boss, accept that it may take a lot of trial and error before achieving that status.

For entrepreneurs and creatives especially, doing what you love can also be incredibly lonely. Humans need social interaction. According to a Harvard Business Review study, half of CEOs experience loneliness in their careers, with first-time CEOs the most susceptible. There are ways to combat feelings of isolation such as forming communities outside work and with other like-minded individuals. But it may be worthwhile to assess whether an environment that provides social interaction is a non-negotiable.

What are some ways to pursue a life you love?

First, don’t quit your job without a plan. Always have a safety net in case it doesn’t work out. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs explains that our basic needs must be met before we can achieve self-actualization. You will not enjoy the work you do if you cannot afford to put food on the table.

Second, it’s also important to consider your desired lifestyle and what kind of career can provide that. For example, if ‘doing good’ is a core value, then you may have to accept a downgrade in pay. If work-life balance is important, then perhaps working for a 9-5 at a medium-sized corporation rather than pursuing a passion is more in alignment with the life you want.

Lastly, work is not the only means to living a life you love. It’s important to diversify your interests to ensure your whole identity doesn’t revolve around your career. This can include hobbies, side gigs, passion projects, spending time with family and friends, or even physical activity.

“When you have money, it’s always smart to diversify your investments. That way if one of them goes south, you don’t lose everything. It’s also smart to diversify your identity, to invest your self-esteem and what you care about into a variety of different areas — business, social life, relationships, philanthropy, athletics — so that when one goes south, you’re not completely screwed over and emotionally wrecked.”

Tim Ferris

How can you find meaning in your work?

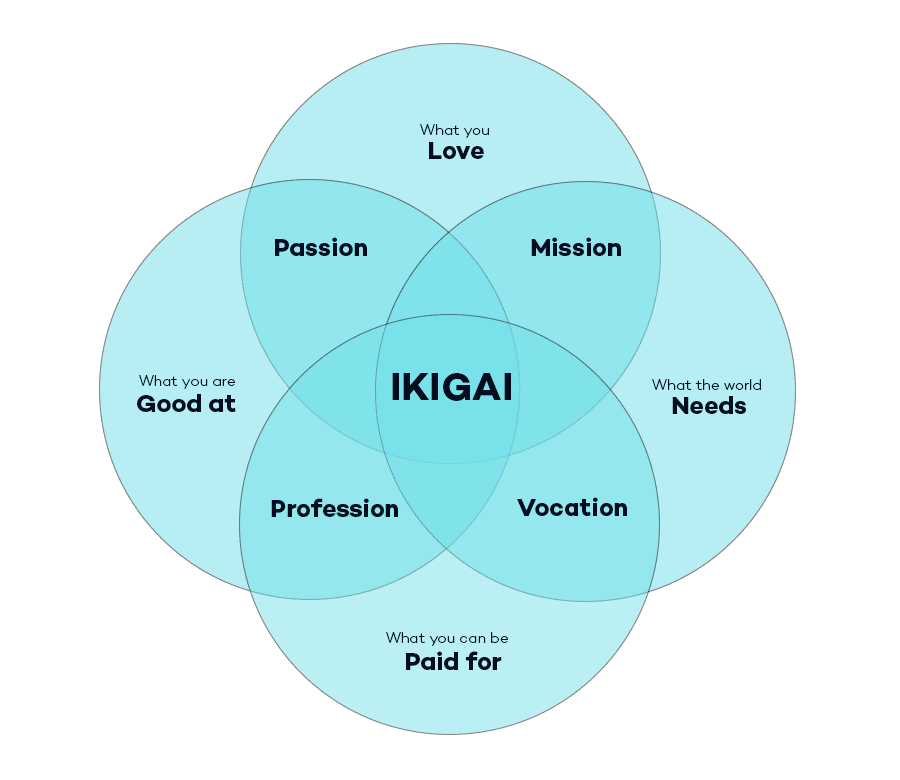

Ikigai is a Japanese term roughly translated as ‘a reason for being’. It is often represented as a Venn diagram (shown below) as a guide for discovering your life’s purpose. Your Ikigai is doing what you love, what you’re good at, what the world needs, and what you can be paid for.

A key component of Ikigai is the ability to see the direct impact of your work. Ikigai can even increase longevity. Japanese Okinawans who embody Ikigai are known to live well past the age of 100.

Finding your Ikigai does not need to be in a grandiose way either. In fact, humans have the incredible ability to create meaning out of even the most mundane, or awful, of circumstances. In Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, which he wrote after enduring the concentration camps, he explains:

‘To choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way…that the sort of person the prisoner became was the result of an inner decision, and not the result of camp influences alone…It is this spiritual freedom — which cannot be taken away — that makes life meaningful and purposeful.”

Perhaps the answer is to focus less on loving the work you do and more on doing work that is meaningful.

What does it mean for a person to function at their peak? Peak performance means that all basic needs are met so the mind and body are nourished, which allows for the highest level of success. It’s about long-term, consistent, and sustainable growth.

Often, peak performance is a term used in the athletics world. Athletes are in a constant cycle of training and recovery, learning their body’s cues in order to perform their best in matches or competitions. But the same mentality and techniques can be applied to entrepreneurship, the business world, or to anyone who is striving to live their best life. Superhuman status is not just for the elite.

“Peak performance in life isn’t about succeeding all the time or even being happy all the time. It’s often about compensating, adjusting, and doing the best you can with what you have right now.” — Ken Ravizza, Sport Psychologist

Ken Ravizza, Sport Psychologist

The power of the to-do list

It may seem simple, but one way to achieve peak function is by writing down goals and to-do lists for accountability. The goals should be SMART goals: specific, measurable, actionable, relevant, and time-bound. But a to-do list can include everything from long-term planning to what to accomplish before breakfast the next day. To-do lists help to organise the mind in a more linear fashion and create space to focus on the present moment rather than stressing about what’s to come.

It is also important to not rigidly adhere to a to-do list. Psychologists have found that a growth mindset is more indicative of long-term success and motivation. Part of being a highly successful person is learning to adapt to the inevitable fluctuations of life.

Mindfulness & mental health

Mindfulness and meditation can help with stress and the ability to remain calm under pressure. Prioritising mental health is equally important as physical health and the items on a to-do list. Goals are important, but they also need to be sustainable.

In fact, in a study in The Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, athletes who performed just twelve minutes of meditation a day showed higher mental resilience than those who didn’t. They also had more improved focus during training. Rest and recovery can often seem counterintuitive when schedules are jam-packed and the lists endless, but ultimately, taking the time to be present and slow down will lead to more effective results.

Diet, nutrition & sleep

A healthy diet, nutrition, and adequate sleep are essential to achieve peak performance. Sleep debt — fewer than seven hours of sleep — may be an ‘unrecognised, but likely critical factor in reaching peak performance’, says Cheri Mah, researcher at the Stanford Sleep Disorder Clinic and Research Laboratory. There is a strong correlation between diet and nutrition and quality of sleep. For example, sugar, caffeine, and alcohol negatively impact sleep, whereas eating a Mediterranean diet, and a diet high in Omega fatty acids, may lead to more restful sleep (Godos et al., 2019).

Many high performers work around their ‘peak performance hours’, which is the time of day when a person is most efficient based on the body’s chronotype and circadian rhythms. In other words, knowing whether one is a night owl, or a morning bird can help determine the day’s structure for optimal success.

The importance of deep work & flow

Lastly, the ability to be in flow is not only a factor in success but also happiness and overall life satisfaction. ‘Flow’, a term first coined by positive psychologist, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, refers to being completely immersed in the task at hand. It can be achieved by avoiding multitasking, focusing on quality of the work rather than doing as many things as fast as possible, and by doing a task that is enjoyable.

In the book, The Leading Brain: Powerful Science-Based Strategies for Achieving Peak Performance, the authors explain that optimal focus also requires some level of stress. Too much stress will inhibit focus, and too little leads to a lack of motivation. To achieve deep flow, then, there needs to be some sense of urgency in the work. There needs to be a purpose driving the task.

Conclusion:

Peak performance is not achieved overnight. It requires consistent practice, having clear goals, and holding oneself accountable, while also maintaining a healthy and balanced lifestyle. Anyone can achieve peak performance and success by implementing the right habits.

More on sleep

- “Studies show that reducing sleep by as little as 1.5 hours for even a single night could cause a reduction of daytime alertness by as much as 32 percent, while also doubling the person’s risk of sustaining an occupational injury.” (Read more)

- The Power of Sleep: Unlocking the Secrets to Success with Elite Sports Sleep Coach Nick Littlehales

- Cracking The Performance Code with Justin Roethlingshoefer

- Performance improvement lessons from leading sleep expert Pat Byrne

- The impact of sleep on performance with Motty Varghese