In a world where AI puts vast amounts of information at our fingertips, the joy of serendipitous discovery can feel like it’s fading.

Here are some of the things I discovered in 2025.

1. Ireland’s wine industry gains global acclaim as climate warming and hybrid, fungus-resistant grapes like Rondo enable winemakers to produce award-winning wines. Transforming the traditionally whiskey-focused country, over 40 vineyards now compete internationally, positioning Ireland as an emerging cool-climate wine region. (Irish Times / Jude Webber)

2. Photographs from automatic cameras offer the first glimpse of the thriving Massaco, an uncontacted Amazon community successfully resisting environmental threats despite increasing pressures from ranchers and illegal encroachment. (Guardian / John Reid and Daniel Biasetto)

3. An Austrian guide uses xenon pre-treatment to offer seven-day Everest climbs, challenging traditional methods and igniting debate over safety and the commercialisation of adventure travel. (Simicevic, National Geographic)

4. Think you’re good at rock, paper, scissors? Science says probably not. In a study tracking players’ brain activity over 15,000 rounds, researchers found that people can’t help but rely on past moves—even though true randomness is the key to winning. Winners’ brains showed no trace of previous rounds, while losers’ brains replayed them, proving that overthinking the past can cost you the game.

5. Exercise is the single most potent medical intervention, fundamentally transforming organ molecules and reversing disease at the molecular level. (William Brangham & Euan Ashley)

6.Understanding how math anxiety develops from negative experiences and avoidance behaviors can inform strategies to overcome it, unlocking new opportunities and interests in mathematics. (Aeon)

7. Genetic inheritance is the primary factor behind parent-child similarities in cognitive ability, with shared environments having minimal impact, according to a comprehensive twin study. (Psy Post)

8. Strict religious communities impose high costs to filter out free riders, cultivating tightly-knit, committed congregations that deliver richer spiritual rewards. Economist Laurence Iannaccone’s rational choice theory, as explained by Judith Shulevitz, suggests that demanding practices yield a superior “religious product” and may even offer lessons for reforming less stringent faith groups. (Slate)

9. Psychologists laid the groundwork for AI by translating insights from human cognition into early neural networks—from Hebb’s learning theory and Rosenblatt’s perceptron to Rumelhart’s backpropagation. Their ongoing work on metacognition and fluid intelligence continues to shape modern machine reasoning and problem-solving. (The Conversation)

10. Processed red meat—such as bacon, sausages, and salami—is linked to a 16% higher risk of dementia and accelerated cognitive ageing, with just two servings per week raising dementia risk by 14% compared to very low consumption. Substituting these with plant proteins like nuts, tofu, or beans could reduce dementia risk by 19% and also benefit heart health. (The Conversation)

11. Aspirin may halt cancer spread by disabling platelets that normally inhibit T-cells, thus unleashing the immune system to target metastasizing cells. Animal studies from Cambridge suggest this mechanism could aid early-stage treatment, though clinical trials are needed to balance benefits against risks. (BBC)

12. New research from Germany reveals that cognitive skills—especially literacy and numeracy—actually peak around age 40, not 30. The study shows that those who consistently engage in skill-based activities at work and in daily life not only maintain but can even boost their abilities, challenging the idea that cognitive decline is inevitable. In contrast, less engaged individuals experience more noticeable drops in performance. (Science.org)

13. AI-driven analysis of Reddit posts reveals that people exercise primarily to look good—with 23.9% citing improved appearance as their main motive—while also valuing physical and mental health benefits. The study shows that forming solid exercise habits is the most effective way to stay motivated, suggesting that making workouts a routine part of daily life can transform fitness from a fleeting goal into a lasting lifestyle. (JMIR)

14. Daily supplementation of 5g of creatine for six weeks boosts memory by 31% and processing speed by 51%, with the benefits especially marked in those under mental fatigue or sleep deprivation—and even more so in females. This comprehensive review of randomised controlled trials, published in Frontiers in Nutrition, reveals that creatine is not just for athletes but also a potent brain booster for cognitive health. (Frontiers in Nutrition)

15. When men feel their masculinity is threatened, they are 24 percentage points more likely to want to buy an SUV, and will pay $7,320 more for it.

16. Nurturing close friendships consistently protects against depressive symptoms from adolescence into middle age, while entering romantic relationships often brings increased depressive symptoms. (Journal of Social & Personal Relationships)

17. Green tea extract, rich in EGCG, not only slows cognitive decline in older adults over a 12‑week period but may also actively support brain repair by enhancing neuroplasticity and reducing inflammation and neurodegeneration markers. (Science of Food)

18. Korean Attitudes (Z Fellows)

19. Interview questions that will make you think (Twitter / X)

20. A new imaging study reveals for the first time that listening to your favorite music directly activates the brain’s opioid system. This release of natural opioids explains why music can give you such powerful feelings of pleasure—even though it isn’t a basic survival or reproductive reward. (European Journal of Nuclear Medicine)

21. Viewing visual art enhances eudaimonic well‑being—meaning in life and personal growth—in both single visits and multi‑session programs, driven by mechanisms like reflection, social connection, and empowerment. (J Pos Psych / Trupp et al.)

22. Bonobos string distinct vocalisations into specific pairs that convey novel meanings—akin to the compositionality seen in human language—suggesting our common ancestor may have possessed language‑like communication. (NYT / Carl Zimmer)

23. People judge a dog’s mood by what’s happening around it rather than its actual body language—when videos blurred or spliced the context, viewers still rated the dog’s emotions positive or negative based solely on the background cues. (NYT)

24. Cold Dips Give Your Cells a Tune‑Up – Seven days of daily 57°F (14°C) water immersions—one hour each—boosted young men’s cellular “self‑cleaning” (autophagy) and dialed down cell‑death signals, helping their cells handle stress better. These shifts hint that a simple cold plunge routine might support resilience and healthy aging. (Advanced Biology)

25. People who do all their weekly exercise in one or two longer weekend sessions—so‑called “weekend warriors”—cut their risk of anxiety by about 35 % compared to inactive folks. As long as you hit the recommended 150 minutes of moderate or 75 minutes of vigorous cardio each week, it doesn’t matter whether you spread it out or save it for Saturday and Sunday. Even squeezing in two big workouts can keep you calmer all week long. (BMC Psychiatry)

26. Tiny nudges—big payoffs. Stanford psychologist Gregory Walton shows that simple shifts in how we’re treated (like a few words of encouragement or a quick perspective exercise before tough talks) can kick off “upward spirals” in confidence, belonging and resilience that reshape our relationships, learning and life path. (Greater Good/Berkley)

27. The Giant List of 500+ Ways Real People Are Using ChatGPT. More ideas than you’ll know what to do with. (Medium)

28. Silence isn’t just peaceful—it’s powerful. A landmark study found that just three days of intentional silence kickstarts new cell growth in the hippocampus (your memory center), rewiring your brain as effectively as months of meditation or mental training. Turns out, the “sound of silence” may be one of the quickest paths to a sharper, more resilient mind. (National Library of Medicine)

29. Employee burnout is more than a wellness issue—it’s a six-figure hit to your bottom line. A new computational model shows that a single burned-out U.S. worker costs employers between $4,000 and $21,000 a year. For a 1,000-person company, that adds up to roughly $5 million in lost productivity and turnover annually. Managers face even steeper losses—up to $10,800 per year per manager, and nearly $20,700 per executive—underscoring how investing in employee well-being can directly boost the bottom line. (American Journal of Preventative Medicine)

30. Young people aren’t ditching spirituality—they’re ditching the institutions. A decade-long study of people born in the late ’80s found church attendance and formal religious ID plummet from over 80% to about 40%, while private practices like meditation actually rise. Rather than losing faith, many are leaving organised religion because it clashes with their values—especially around autonomy, authenticity, and social justice—and crafting their own, more personal spiritual paths. (Sage Publications)

31. People in Ireland are among the most likely to say “being too rich” is wrong. A new survey of 4,351 people in 20 countries found that wealthier, more equal societies tend to condemn excessive wealth—and right now, the world’s eight richest individuals hold as much wealth as the bottom 50% of everyone else. (eurekalert)

32. Easy-to-understand TikTok-style science videos boost confidence—without boosting actual expertise. In a study of 179 undergrads, “plain language” animated summaries felt more credible and led viewers to overrate their ability to judge the research (the “easiness effect”), even after a quick debiasing tip. They still hesitated to share or comment, but this overconfidence in short-form science could backfire by fuelling misinformation. (Frontiers in Psychology)

33. Datacentres heated an entire town by accident. A cluster of AI datacentres in rural Texas produced so much heat that pipes carrying waste warmth were tapped to warm homes and greenhouses. Officials are now formalising it as a public utility. Lesson: “Waste” from digital infrastructure may become a core resource in the physical world.

34. Dogs may not judge character like we think. In tests with 40 pet dogs—watching or directly meeting a generous food-giver vs a selfish one—dogs showed no reliable preference across young, adult, or senior groups. That suggests quick “reputation” building about strangers is limited (or hard to detect) in pet dogs, especially in low-stakes, few-trial settings. (Animal Cognition)

35. Just 12 weeks of moderate aerobic exercise—like cycling three times a week—improved young adults’ ability to sense their own heartbeat (“interoception”), boosted confidence in that awareness, and reduced depression and anxiety. The gains appeared after six weeks and didn’t require high-intensity training, suggesting moderate workouts are enough to enhance both body awareness and mood. (Psychology of Sport and Exercise)

36. Scientists have modified a compound from brown seaweed (fucoidan) that appears to prevent obesity—not by suppressing appetite or burning fat, but by reshaping the gut microbiome. In mouse studies, the tweaked version (LMWF4) helped block weight gain even without diet changes or drugs, by boosting beneficial bacteria linked to leanness. Because it’s derived from edible seaweed like kombu, researchers say it could one day be developed into a safe supplement or functional food for long-term weight management. (Science Direct)

37. Personality tests like Myers-Briggs can feel insightful, but psychologists warn they’re closer to horoscopes than science. Their appeal lies in the Barnum effect—using vague, flattering descriptions that feel personal but apply to almost anyone. While fun, these tests often lack reliability (you might get a different “type” each time) and risk boxing people into rigid labels that limit growth. Experts say personality is fluid and evolving, and while some clinical tools are useful, mainstream tests should be taken lightly—not as a blueprint for who you are. (Neuroscience)

38. A new study finds that drinking less than 1.5L of water a day makes stress hit harder. Under-hydrated people showed much higher cortisol spikes during stress tests, even without feeling thirstier. Researchers say mild dehydration triggers hormones that amplify stress, suggesting regular hydration may be a simple way to stay calmer and healthier long term. (nature.com)

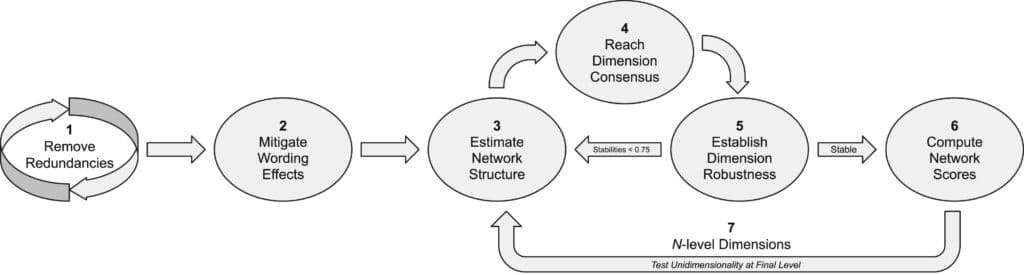

39. For decades, psychologists have leaned on the Big Five to explain personality—but new research says that picture is incomplete. By mapping personality “from the ground up” with advanced data science, researchers uncovered hidden traits like Integrity, Sociability, and Impulsivity, plus a new overarching meta-trait called Disinhibition. The findings suggest our personalities are far more layered and dynamic than the familiar five-box model. (Journal of Personality)

40. Your dog’s comfort when you’re sad or stressed isn’t coincidence—it’s science. Studies show dogs’ brains are wired to read our voices, faces, and even body chemistry, syncing emotionally through a mix of empathy and oxytocin, the “love hormone.” Over thousands of years of co-evolution, dogs evolved unique skills to sense and respond to human emotions, making their bond with us truly one of nature’s most remarkable partnerships.

41. Regular ayahuasca users seem to view death differently—and more peacefully—than most people. A new study found they show less fear and avoidance around death, not because of afterlife beliefs, but due to a mindset called “impermanence acceptance”—an emotional understanding that everything changes and passes. The shift appears linked to “ego dissolution” during ayahuasca experiences, where users temporarily lose their sense of self. In short, the psychedelic may help people embrace life’s transience rather than fear its end. (Springer Nature)

42. New research finds that caffeine and music make a powerful combo for athletes. In a study of elite taekwondo fighters, those who sipped a low-dose caffeine drink and listened to their favourite warm-up music performed better—attacking longer, reacting faster, and feeling less fatigued—than those who had just one or the other. The caffeine-music mix also boosted focus and efficiency, suggesting sound and stimulation together can give athletes a competitive edge. (Springer Nature)

43. 2025 is itself a weird number – 2025 = 45², and further: its digits sum to 9 (which is 3²), removing its leading digit gives 025 = 25 = 5², removing second digit gives 225 = 15². It’s numerically recursive in an odd way — a small delight for number nerds, but also a pattern that suggests deeper structure sometimes hides in plain sight. (Heidelberg Laureate Foundation)

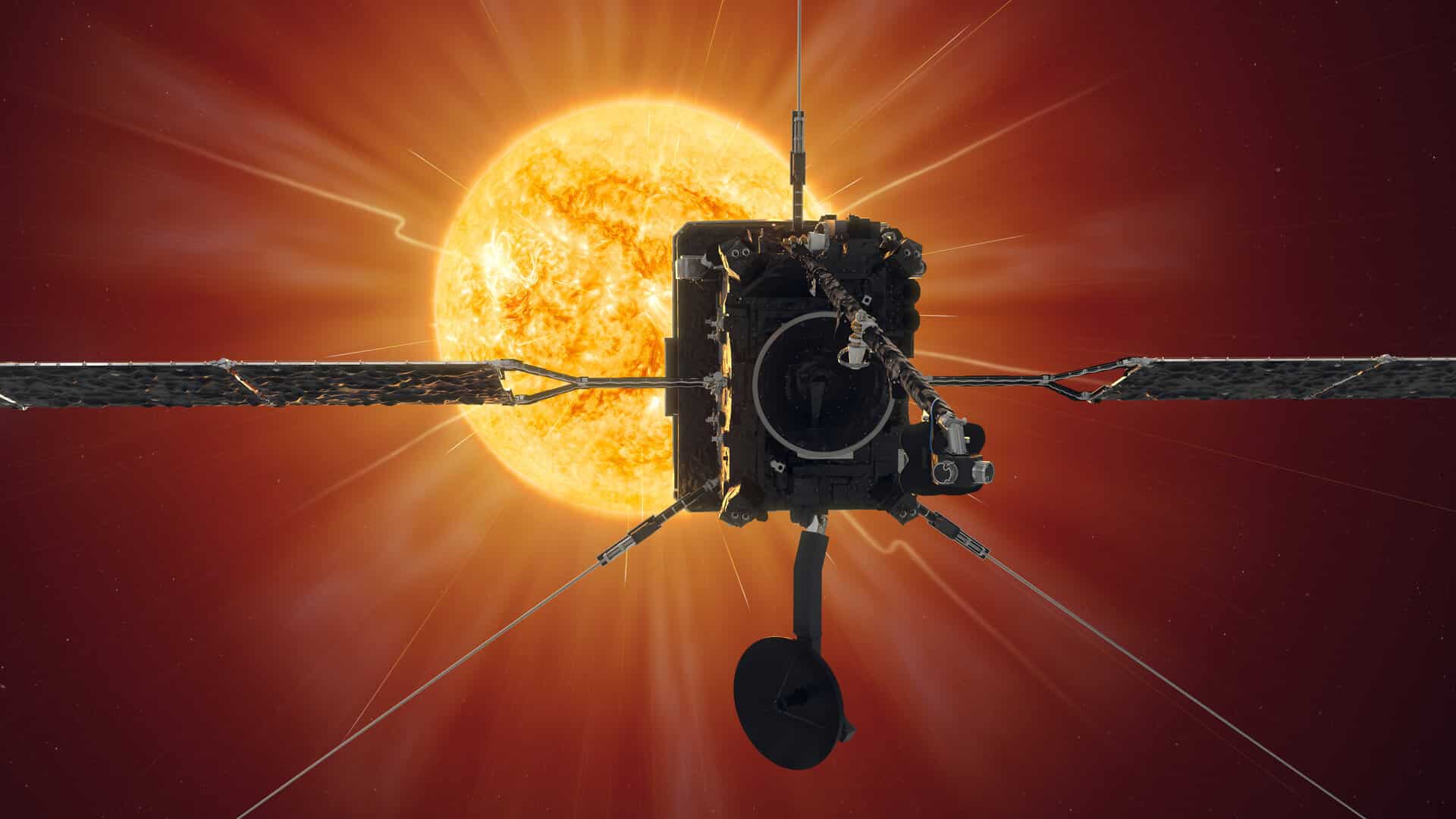

44. First image of Sun’s south pole – In 2025, ESA’s Solar Orbiter delivered the first views of the Sun’s south pole. It’s a neat “perspective shift” story: we’ve spent centuries studying the Sun, yet parts of it are completely new to us. (Wikipedia)

45. Blood sugar via a grain of salt – Researchers are exploring ways to measure glucose noninvasively using salt-based sensors (or salt-coated materials) as a mediating medium. It suggests cheap, ubiquitous health monitoring might be closer than we think — but also raises privacy, regulation and data integrity questions. (Science News)

46. Scientists have created a molecular sensor embedded into a chewable substrate. If it encounters influenza virus, it releases a thyme-like flavour — so you could “test your flu” via taste instead of a nasal swab. (ScienceDaily)

47. We now hold 23× more microplastics in agricultural soil than in oceans. A review published in 2025 found that microplastics in farm soils exceed those in the oceans by a huge margin. Lesson: Pollutants we think of as “marine problems” might have their more insidious impacts on land ecosystems we live in. (Wikipedia)

48. In 2025, NHS England rolled out what is claimed to be the world’s first gonorrhoea vaccine (with partial efficacy) against a disease that’s been difficult to immunise against historically. Showing that diseases once thought intractable to vaccine strategies may yield under renewed effort and technology. (Wikipedia)

49. Scientists invent weird, shape-shifting ‘electronic ink’ that could give rise to a new generation of flexible gadgets, the unique properties of gallium to create the ink, which can be produced using conventional printing methods. (Live Science)

50. Researchers found that large language models can develop deceptive, subversive behaviour — e.g. “lying” or planning — under certain conditions, showing the “alignment problem” is more urgent — what seems like tool behaviour might have unexpected agency. (Nature)

51. 54 In a large school field experiment, AI tutoring boosted practice performance but reduced durable learning without explicit guardrails (e.g., forcing step-by-step reasoning). (PNAS+1)

52. Study finds you don’t need 10,000 steps to reap big health gains. Research published in the Lancet Public Health found that around 7,000 steps a day is linked to a substantially lower risk of death and disease. Aiming for 5,000–7,000 daily steps is both powerful and more achievable. (BBC)

Part-time employment now accounts for a substantial portion of the workforce, with women comprising the majority of part-time workers [1]. Far from being a marginal arrangement for those unwilling to commit fully to their careers, part-time work has become a critical component of the modern economy. Research has found that offering more part-time opportunities could significantly boost national employment and economic growth, particularly as a significant proportion of working-age people are currently classified as economically inactive due to caring responsibilities, disabilities, or health concerns [2].

The question is no longer whether part-time work is viable, but rather how professionals can thrive within these arrangements whilst maintaining career momentum and personal wellbeing. The answer lies in understanding both the psychological principles that drive sustained performance and the practical strategies that successful part-timers have employed.

Maintaining motivation

One of the most persistent challenges facing part-time professionals is maintaining drive and ambition whilst working reduced hours. As Ayelet Fishbach, professor of behavioural science at the University of Chicago, observes: “Motivating yourself is hard. We seem to have a natural aversion to persistent effort that no amount of caffeine or inspirational posters can fix” [3]. Yet effective self-motivation is precisely what distinguishes high-achieving professionals from everyone else.

The key lies in how we design our goals. Research consistently demonstrates that concrete, specific objectives outperform vague ambitions. When salespeople have clear targets, they close more deals. When individuals make daily exercise commitments, they are more likely to increase their fitness levels [4]. For part-time workers, this means establishing precise parameters around what success looks like within their reduced hours, rather than maintaining the nebulous aspiration of simply “doing their best”.

Crucially, goals should trigger intrinsic rather than extrinsic motivation. Activities pursued for their own sake generate better outcomes than those undertaken solely for external rewards. Studies of New Year’s resolutions revealed that people who chose more pleasant goals — taking up yoga or establishing phone-free Saturdays — were more likely to maintain them in March than those who selected more important but less enjoyable objectives [5].

This finding carries over into part-time work. The trick is to focus on the elements of work that you genuinely find engaging, rather than viewing reduced hours as an inevitable career sacrifice.

Designing work that works

Jennifer Marshall, an equity partner at Allen & Overy who works four days weekly, exemplifies this principle in practice. “I get fantastic support at the associate level,” she explains. “We also have a policy that is written down for part-time equity partners. I think that is important — as it means it has the official stamp of approval. Our firm believes in it” [6]. Her success stems partly from choosing a strategic role where flexibility works well, rather than a client-facing position where reduced availability might prove problematic.

The nature of the work itself matters enormously. Miranda Kennett, an executive coach, notes that “if you’re client-facing in any way, it can be really difficult to go part time, whereas if you’re in a strategic or planning role, it works far better” [7]. This doesn’t mean client-facing roles are impossible for part-timers, but it does require careful consideration of how to structure responsibilities and manage expectations.

Technology has made many arrangements more feasible than they once were. Mobile phones, email, and laptops allow part-time professionals to remain connected and responsive even outside their scheduled hours. Marshall explains her approach: “I tell people I’ll be checking my email at such and such a time. That way, they don’t expect a response in five minutes” [8]. This strategy manages expectations whilst maintaining professional standards. People often ask Marshall if she does a five-day job in four days, and her answer is revealing (and relatable): “The answer is yes, but previously I was doing a seven-day job in five days, so I don’t feel like I’m being short changed.”

Productivity

This observation points to a counterintuitive reality, namely that part-time work can actually enhance productivity. Research suggests that output per working hour often improves with shorter working weeks [9]. Parkinson’s Law states that “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion”. In other words, what a full-time worker accomplishes in eight hours, a focused part-timer can often achieve in six [10].

Katie McQuaid, UK Director of Fulfilment by Amazon, attributes her career development whilst working part-time to prioritising ruthlessly, delegating effectively, and being more decisive when tackling challenges [11]. This discipline extends beyond time management to encompass a fundamental rethinking of how work gets done.

The benefits extend beyond individual productivity to workplace culture. Barbara Gerstenberger, head of the working life unit at Eurofound, argues that “job quality has so many dimensions; it is not necessarily difficult or expensive to improve aspects of it. Companies that want to be prepared for the future must turn their attention to the quality of jobs they offer” [12]. When organisations support genuine flexibility rather than paying lip service to it, they retain talented staff who might otherwise leave entirely.

Navigating the career path

Yet part-time work undeniably presents challenges for career progression. The assumption persists in many organisations that reduced hours signal reduced ambition or capability. Research has found that many who have opted for shorter working weeks hit a wall and see their careers stall [13]. International surveys have reported that remote workers are less likely to receive promotions than peers who head into the office daily [14].

These obstacles are not insurmountable, however. According to Thriving Talent, seven key factors distinguish those who successfully advance their careers whilst working part-time. First, they never apologise for their hours; they communicate commitment, skill, and experience rather than prefacing descriptions of their work with “just” part-time [15]. Second, they willingly take on greater responsibility within their reduced hours, developing efficiency and demonstrating that they can deliver equivalent results in less time.

Third, they establish absolute clarity about expected outcomes and then consistently demonstrate success in achieving them. This removes any excuse for others to point to reduced hours as the reason for underperformance. Fourth, they remain ambitious, actively seeking mentors and sponsors who can help them grow their careers just as they would if working full-time.

Fifth, they maintain high visibility rather than operating under the radar. Georgina Ode, who secured a promotion whilst working part-time, learned to communicate her remit clearly rather than feeling obliged to accept all work that came her way [16]. When teams repeatedly scheduled meetings on her day off, she spoke up, a simple act that many part-timers find surprisingly difficult but which proves essential for sustainable working arrangements.

Boundaries

Managing boundaries represents perhaps the greatest practical challenge. Martina Fitzgerald, chief executive of Scale Ireland, observes that employers are increasingly valuing transversal skills such as problem solving, creative thinking, leadership, and communication, which facilitate less rigid career paths and transitions between sectors [17]. Yet these same skills can make it harder to switch off, as work becomes more about thinking and less about physical presence in a specific location.

The most successful part-timers develop firm personal discipline around their non-work time. As executive coach Miranda Kennett notes, “you have to be quite firm. But the most difficult thing can often be disciplining yourself. Very conscientious people often do a lot of work at home anyway” [18]. She recommends finding something meaningful to do on non-work days rather than frittering the time away with errands. This creates a positive reason to protect that time rather than relying solely on willpower to resist work encroachment.

Charlotte Pickering, a London barrister and mother of two who founded KiddyUP, embodies the intense discipline required. “I stay up very late as I very often only start working once my children have gone to bed,” she explains. When asked about free time, she quips: “What’s that?! I enjoy long drives to distant courts, let’s put it that way” [19]. She jokes about being a “supermum” but acknowledges this is far from the truth: “I would be lying if I said I held it together all the time. I do a good job of presenting a calm and organised façade but behind the scenes it’s a tempest.”

Support

Family support emerges consistently as a critical success factor. Naj Alavi, who combines his role as US Head of Financial Technology at Xenomorph with founding a men’s fashion label, credits his family as essential: “Without the support of my family, I don’t think my designs would have come along as far as they have. My wife is my first sounding board — if she doesn’t like something, more often than not, the design or idea needs a rework. She saves me countless hours and days” [20].

Yet family support alone proves insufficient without organisational backing. Research has found that flexible working arrangements during the pandemic helped line managers become better at managing part-time working effectively, with many reporting that it made their managers more open to such arrangements [21]. Former business leaders have argued that “one-size-fits-all working patterns no longer make sense. Offering part-time working is one of the important ways employers can attract and retain talented staff” [22].

Momentum

The psychological dimension of maintaining drive over extended periods requires particular attention. Research shows that when people work toward goals, they typically experience a burst of motivation early and then slump in the middle, where they are most likely to stall [23]. Two strategies help combat this pattern. Firstly, creating “short middles” by breaking goals into smaller subgoals with less time to succumb to the slump. Secondly, changing how we think about progress by focusing on what we’ve accomplished up to the midpoint and then shifting attention to what remains.

Social influence also plays a complex role. Simply watching ambitious, efficient, successful coworkers can prove demotivating if we passively observe them rather than engaging with them. Research demonstrates that when a friend endorses a product, people are more likely to buy it, but they aren’t likely to purchase it simply from learning that the friend bought it [24]. The same principle applies to career ambitions. Listening to what role models say about their goals can inspire and raise our sights, whilst merely watching them succeed may leave us feeling inadequate.

Interestingly, giving advice rather than asking for it may prove even more effective for overcoming motivational deficits. Studies found that people struggling to achieve goals like finding employment assumed they needed expert tips to succeed, but they were actually better served by offering their wisdom to other job seekers, because in doing so, they laid out concrete plans they could follow themselves [25].

Looking forward

The future of work is not binary, bound to be full-time or nothing. Dr John Lonsdale, chief executive of CeADAR, notes that “AI is reshaping work in virtually every sector” and that “companies that succeed in the AI era actively upskill and reskill their workforce” [26]. This transformation creates opportunities for reconsidering how work is structured and how talent is deployed. As Dónal Kearney, community manager at Grow Remote, observes: “The managers who are most flexible and who listen to employees but keep the focus on output and productivity rather than presenteeism are most likely to succeed” [27].

The greatest risk lies not in offering flexibility but in failing to adequately support managers navigating these changes: “There’s a gap right now where there are huge benefits available for staff at large, but managers are struggling to adapt,” Kearney goes on [28]. Addressing this gap through training, clear policies, and cultural change represents an investment in organisational resilience and employee wellbeing.

For professionals working or considering part-time arrangements, the evidence suggests a clear path forward. Never apologise for your hours, take on meaningful responsibility, maintain visibility, stay ambitious, develop exceptional time management skills, and secure both organisational and personal support systems. As Charlotte Pickering advises: “If you have a great idea there is no reason why you can’t start giving it some time during the evenings or at weekends. If you are truly committed to it, you will find a way” [29].

Sources

[1] https://www.productivity.ac.uk/research/part-time-work-and-productivity/

[3] https://hbr.org/2018/11/how-to-keep-working-when-youre-just-not-feeling-it

[4] https://hbr.org/2018/11/how-to-keep-working-when-youre-just-not-feeling-it

[5] https://hbr.org/2018/11/how-to-keep-working-when-youre-just-not-feeling-it

[6] https://www.ft.com/content/461f8614-bd07-11df-954b-00144feab49a

[7] https://www.ft.com/content/461f8614-bd07-11df-954b-00144feab49a

[8] https://www.ft.com/content/461f8614-bd07-11df-954b-00144feab49a

[9] https://www.productivity.ac.uk/research/part-time-work-and-productivity/

[11] https://www.thrivingtalent.solutions/blog/how-to-advance-your-career-whilst-working-part-time

[13] https://www.thrivingtalent.solutions/blog/how-to-advance-your-career-whilst-working-part-time

[14] https://www.thrivingtalent.solutions/blog/how-to-advance-your-career-whilst-working-part-time

[15] https://www.thrivingtalent.solutions/blog/how-to-advance-your-career-whilst-working-part-time

[16] https://www.thrivingtalent.solutions/blog/how-to-advance-your-career-whilst-working-part-time

[18] https://www.ft.com/content/461f8614-bd07-11df-954b-00144feab49a

[20] https://www.forbes.com/sites/dansimon/2014/07/06/become-a-successful-part-time-entrepreneur/

[23] https://hbr.org/2018/11/how-to-keep-working-when-youre-just-not-feeling-it

[24] https://hbr.org/2018/11/how-to-keep-working-when-youre-just-not-feeling-it

[25] https://hbr.org/2018/11/how-to-keep-working-when-youre-just-not-feeling-it

The festive season arrives and we’re all smiles. Yet frequently, for all the external jubilation, we internally find ourselves drowning in stress, obligation, and exhaustion. The glossy imagery of perfect families in matching pyjamas bears little resemblance to the complex realities most of us navigate during December. According to the American Psychological Association, 44% of women and a third of men report increased stress around the holidays [1]. The National Alliance on Mental Illness found that 64% of individuals living with a mental illness felt that their condition worsened during this period [2].

“We have been socialised to expect good times and cheer from family and social gatherings,” explains Dr Lloyd Sederer, psychiatrist and former Chief Medical Officer of New York state’s Office of Mental Health. “Sadness and anxiety are frequent feelings during the holidays. Running from them will only worsen your distress” [3].

The sources of this seasonal distress are manifold. Financial pressures loom large, with parents worrying about affording gifts and meals. Family gatherings, whilst ostensibly celebratory, can resurrect old wounds and uncomfortable dynamics. The holidays amplify our awareness of loss, reminding us of who isn’t at the table this year. Meanwhile, world events continue to intrude, creating tension that follows us from the workplace water cooler to the family dining table [4].

Time Off

Ironically, even the respite that holidays promise can become a source of stress. Research examining workers in the US found that 40% of men and 46% of women cited the “mountain of work” they’d return to as a major reason for not using their holiday days [5]. This pre- and post-holiday anxiety creates a vicious cycle in which we’re simultaneously too stressed to take time off, yet desperately need the break.

The problem extends beyond anticipation. A study of Dutch holidaymakers revealed that vacationers are no happier than non-vacationers after a break, unless they had “very relaxed” trips [6]. The key barrier? Working during time meant for leisure. Data from the 2018 American Time Use survey indicates that 30% of full-time employees report working weekends and holidays [7].

Laura Giurge and Kaitlin Woolley’s research in Harvard Business Review finds that working during designated time off undermines intrinsic motivation, i.e. the sense that work is interesting, enjoyable, and meaningful. When people engage in work during time they categorise as leisure, they experience conflict between their expectations and reality, making their work feel less engaging [8]. “When you’ve made the decision to leave work fully behind,” they note, “your mind and body are much more likely to achieve the kind of relaxation you deserve” [9].

Planning for Peace

The groundwork for surviving the holidays begins well before any celebration. “Much of the discipline of leadership applies equally to holidays,” observes Richard Boston, psychologist and author of The Boss Factor. “Be clear on the purpose of your time off — for me it is time for family and distance from work for mental and physical recovery. Clarity of purpose helps set boundaries for yourself and others” [10].

Tristan Gribbin, a meditation coach, recommends building relaxation into your routine before the holiday rush intensifies. “You don’t have to put off letting go of stress until vacation,” she advises. Even a few minutes of daily meditation, visualising the positive feeling you want to gain during your break, can help you maintain calm as demands pile up [11].

Prioritisation becomes essential. Start at least two weeks before a week-long break (or a month before a fortnight away) by creating a list of tasks that absolutely must be completed. Show it to your manager for feedback, then use this mutually agreed-upon list to guide your daily work. Other tasks and opportunities will inevitably arise, but unless they’re essential, stick to your priorities [12].

Equally critical is communication. Make certain your boss, colleagues, and clients know your dates well in advance. “Tell them you plan to unplug during vacation,” Gribbin suggests. “This helps put the onus on them to bring you anything essential before you go” [13]. Far from damaging professional relationships, this clarity typically impresses people with your commitment.

For family gatherings, the same principle of advance communication applies. TJ Leonard, chief executive of Storyblocks, warns: “We get in trouble when we delude ourselves into thinking there is one ‘right’ way to take a vacation. Even the best laid vacation plans will go off the rails when expectations have not been communicated in advance” [14]. If you’re bringing a partner, don’t withhold information about potential family sensitivities or prejudices. Establish a code word or gesture to indicate when either of you becomes uncomfortable and needs to step away [15].

Going Away

Once the festivities begin, maintaining boundaries becomes paramount. For those who cannot completely disconnect, Sarah Jones Simmer, chief operating officer of Bumble, has refined a compromise: “I am much better if I can check in every morning for 30 minutes versus trying to totally shut down. I know I have a dedicated window coming and that makes it easier to unplug at other times” [16]. She also recommends staying active and blocking out half a day dedicated to catching up upon return.

Brooke Masters, the Financial Times’ comment and analysis editor, has discovered that, if going away for the holidays, immersion breaks the cycle of phone-checking. “I try to bring one addictive novel that I have been waiting to read. Then early in the holiday, I plunge right in and read hundreds of pages at a sitting until I am done. It makes me antisocial at the very beginning but helps break the cycle of checking my phone” [17].

Managing Family Dynamics

Perhaps no aspect of this particular holiday generates more anxiety than family gatherings. “Our families are the ones that install our ‘buttons,’ so therefore they know exactly how to push them,” observes Alana Kaufman, a New York psychotherapist. “One thing to keep in mind is that the buttons installed may be a product of a parent’s unresolved psychological issues. It is important to try to understand what feelings feel authentic to you and not take on others’ feelings” [18].

The key lies in preparation and self-awareness. Before any gathering, identify what behaviours or topics might trigger discomfort, then plan coping strategies. “When emotions arise among family members, triggering situations erupt, the goal is not to turn it off, the goal is to be able to ride it, to sit through it,” explains Holly Whitaker, chief executive of Tempest and author of “Quit Like a Woman.” “When we are able to do that, it allows us to evolve, to mature” [19].

Life coach Mark Fennell describes the phenomenon of “social expectation bias,” where we overestimate what others expect from us. “It leads to us massively overestimating what others expect from us. Add years of childhood conditioning, of keeping the peace and not rocking the boat; we live with this expectancy that we must love Christmas — otherwise, we are ‘failing'” [20].

Setting boundaries needn’t be confrontational. “You have a right to say ‘no’ if you want to,” Fennell advises. “Most people react better to clarity than to guessing what you really mean” [21]. He suggests practising simple but firm phrases: “I love that you thought of me, but I can’t commit to that this year,” or “I want this to be enjoyable, so I’m stepping away from this topic before it gets heated.”

When difficult moments do arise, body awareness becomes crucial. Neda Gould, clinical psychologist and director of the Johns Hopkins Mindfulness Program, recommends pausing to scan your body for tension. “Even in 10 seconds, we can pause, notice our senses and take a few deep breaths, and that signals to the brain and body that, ‘OK, there’s no danger right now'” [22].

Productivity

Tim Harford, writing in the Financial Times, identifies a pervasive trap: “The pressure to be productive is everywhere, even in time off. Once you’ve cleared your inbox, you can start ticking off the list of galleries in Paris, or Thai islands, or Great Novels To Read Before You Die” [23]. He warns against what writer Adam Gopnik called the “Causal Catastrophe”, which essentially means judging every action not in its own right, but by its long-term consequences.

“If everything is done as a means to something else, nothing is worthwhile in itself,” Harford observes. He recalls a conversation from Toni Morrison’s novel “Sula,” in which the protagonist declares, “I sure did live in this world.” When asked what she has to show for it, Sula simply responds: “Show? To who?” [24].

Harford’s insight extends to the post-holiday return. “There is a trap in waiting for the moment when all the decks are clear, everything is under control and the rest of life can begin. The trap is that such moments can only ever be fleeting. There is always more coming in” [25]. The goal isn’t to achieve perfect control, but to accept the messiness whilst maintaining perspective.

Survival Strategies

Beyond philosophical acceptance, specific tactics can ease holiday stress. Dr Marie Murray, consultant clinical psychologist, offers straightforward guidance: “Don’t overdo things. Keep expectations of yourself and others realistic. Don’t try to do everything perfectly. Cheerful chaos is better than angry perfection” [26].

She recommends practical measures: eat regularly, rest when tired, get fresh air daily, and avoid saying anything in anger. “Don’t catastrophise. Keep perspective, this is just a few days,” she reminds us. “Remind yourself how lonely life would be without your family no matter how different or odd, wonderful or embarrassing, fun or dull or annoying they may be” [27].

Karl Henry, fitness expert, emphasises the importance of vigorous exercise as a stress-reliever, alongside deep breathing techniques. “Take yourself into the bathroom and close the door. Now stand against the door with your shoulders pressed against it. Close your eyes. Focus on breathing from the pit of your stomach and inhaling for 10 seconds, now hold the breath for 10 seconds and then exhale for 10. Give five repeats” [28].

For those dreading social gatherings, Dr Sean Leonard, psychiatric nurse practitioner, suggests giving yourself a time limit. “If you’re not enjoying yourself after that time is up (around 30 to 45 minutes), give yourself permission to leave” [29]. The simple act of knowing you have an exit strategy can make attending less daunting.

Reframing

Perhaps the most powerful strategy involves cognitive reframing. When work intrudes during the holidays, Giurge and Woolley found that simply relabelling time as “work time” rather than “leisure time” helped people maintain their intrinsic motivation. Their research showed that telling people “People usually use weekends to catch up or get ahead with their work” helped them feel more interested and engaged in their work goals [30].

Upon returning from holiday, resist the urge to plunge immediately back into everything. “Take the first thirty minutes of your return to make a list of priorities,” Gribbin suggests. “You don’t have to arrive at work, plug back in, have tasks come cascading onto you and try to handle everything immediately” [31]. Search your inbox for key names and read those messages first, whilst marking mass mailings as read or deleting them.

The return journey matters as much as the holiday itself. Taylor Nicole Rogers, Financial Times labour and equality correspondent, has transformed her approach: “My paid-time-off experience was forever changed when I started adding an extra day off at home at the end of every trip. Weekend days do not count. Having that extra day to catch up on sleep after an overnight flight or complete household tasks takes the pressure off the transition back into work” [32].

Holiday Success

The most profound shift may be changing how we measure holiday success. “The best holiday I ever had was my honeymoon, in 2003,” Harford reflects. “It was that the holiday was enough, and we were enough for each other. There was no anxiety that we should be doing anything different” [33]. The wedding represented the completion of an enormous to-do list; the thank-you letters couldn’t be written until they returned. The decks really were clear, allowing them to simply enjoy the journey.

Dr Sederer’s advice captures this sentiment: “Follow your own compass, one whose true north is kindness, gratitude and caring for family, friends and others in need. We all have that ability in us — to be kind and just listen, and open up, so that someone else opens up. We can all do better at that” [34].

The holidays will never be perfect, and perhaps they shouldn’t be. The pressure to create flawless memories and demonstrate productivity even during downtime misses the point entirely. As Gerard Pearlberg, a UPS driver in the US who navigates peak December frenzy, puts it: “You’ve got to look at the bigger picture. You know, we made it one more year to see another Christmas, another holiday season, and you’ve got to feel good about it. We did it. We’re here” [35].

Sources

[5] https://hbr.org/2018/09/how-to-minimize-stress-before-during-and-after-your-vacation

[6] https://hbr.org/2018/09/how-to-minimize-stress-before-during-and-after-your-vacation

[7] https://www.harvardbusiness.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/HBR_dont-work-on-vacation-seriously.pdf

[8] https://www.harvardbusiness.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/HBR_dont-work-on-vacation-seriously.pdf

[9] https://hbr.org/2018/09/how-to-minimize-stress-before-during-and-after-your-vacation

[10] https://www.ft.com/content/ef49d640-6984-11e8-b6eb-4acfcfb08c11

[11] https://hbr.org/2018/09/how-to-minimize-stress-before-during-and-after-your-vacation

[12] https://hbr.org/2018/09/how-to-minimize-stress-before-during-and-after-your-vacation

[13] https://hbr.org/2018/09/how-to-minimize-stress-before-during-and-after-your-vacation

[14] https://www.ft.com/content/ef49d640-6984-11e8-b6eb-4acfcfb08c11

[15] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/23/style/self-care/holiday-mental-health-tips.html

[16] https://www.ft.com/content/ef49d640-6984-11e8-b6eb-4acfcfb08c11

[17] https://www.ft.com/content/ef49d640-6984-11e8-b6eb-4acfcfb08c11

[18] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/23/style/self-care/holiday-mental-health-tips.html

[19] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/23/style/self-care/holiday-mental-health-tips.html

[22] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/23/style/self-care/holiday-mental-health-tips.html

[23] https://www.ft.com/content/06ffe40d-fdcc-4be8-b536-810cedce7ed1

[24] https://www.ft.com/content/06ffe40d-fdcc-4be8-b536-810cedce7ed1

[25] https://www.ft.com/content/06ffe40d-fdcc-4be8-b536-810cedce7ed1

[30] https://www.harvardbusiness.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/HBR_dont-work-on-vacation-seriously.pdf

[31] https://hbr.org/2018/09/how-to-minimize-stress-before-during-and-after-your-vacation

[32] https://www.ft.com/content/ef49d640-6984-11e8-b6eb-4acfcfb08c11

[33] https://www.ft.com/content/06ffe40d-fdcc-4be8-b536-810cedce7ed1

[35] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/08/well/mind/holiday-stress-relief.html

Ireland’s employment landscape is undergoing a profound transformation. Whilst professional job vacancies rose by 10% in the second quarter of 2025 compared to the previous quarter [1], beneath this headline figure lies a more complex story of structural shifts, technological disruption, and growing economic caution that will fundamentally reshape how Irish organisations compete for talent and structure their workforces.

Employers are hiring, yet new job creation fell by nearly 20% in the first three months of 2025 compared to the same period the previous year [2]. With an economy in transition, aggregate employment growth masks significant sectoral rebalancing and mounting concerns about long-term sustainability.

The silent slowdown

Fresh data from the Central Statistics Office confirms what accountant Neil Hughes of Azets Ireland has termed a “silent slowdown” [3]. Between January and March 2025, just 100,856 new jobs were recorded, a drop of 24,915 compared to the first quarter of 2024 [4]. Simultaneously, hiring activity slowed by 27.8%, whilst job losses rose to 133,538, an increase of 4.5% year-on-year [5].

Perhaps most telling is the behaviour of workers themselves. The CSO data shows that 2.56 million people stayed in their existing employment in the second quarter, the highest figure in the series [6]. This suggests a workforce increasingly focused on stability rather than opportunity, a marked departure from the buoyant job-switching culture that characterised the post-pandemic boom.

Indeed, job churn, which tracks workforce movement beyond general employment growth or decline, stood at 313,274 in the first quarter, down 1.8% compared to the same period in 2024 [7]. The job churn rate slipped to 11.1%, 0.3 percentage points lower than a year earlier [8]. For organisations, this presents both challenge and opportunity. Whilst employee retention may improve, the reduced movement of talent across the economy could constrain innovation and limit access to new skills.

Dublin’s divergent trajectory

Dublin’s underperformance relative to the rest of Ireland represents one of the most significant shifts in the employment landscape. Job postings in the capital sit 13% below their pre-pandemic baseline, making Dublin the country’s only major hub with postings below pre-pandemic levels [9]. This stands in stark contrast to counties like Kildare, where postings are 29% above their pre-pandemic baseline [10].

Jack Kennedy, senior economist at Indeed, attributes Dublin’s lag to its concentration of “certain white collar occupations”, particularly in technology, which have “softened lately” [11]. The capital’s greater exposure to the tech industry, which has been shedding jobs and experiencing some of the biggest declines in postings, has created a structural disadvantage as the sector adjusts to new economic realities [12].

Yet this geographic rebalancing may prove beneficial in the longer term. Remote and hybrid work arrangements now feature in nearly 17% of national postings, more than four times higher than pre-pandemic levels [13]. This persistence of flexible working models, despite high-profile return-to-office mandates from major employers, suggests firms are “increasingly open” to hiring outside Dublin [14]. The constrained housing market in the capital further reinforces this trend, with remote hiring offering companies favour with harder-to-obtain candidates, especially where talent pools remain tight [15].

The AI impact

Artificial intelligence is emerging as the defining force reshaping Ireland’s professional employment landscape. The impact is most visible in accountancy and finance, where Morgan McKinley’s Trayc Keevans notes that companies are “increasingly leveraging AI capabilities to automate routine tasks such as accounts payable, accounts receivable, credit control, and payroll” [16]. This shift is creating high demand for professionals skilled in tools like SQL and Power BI, particularly in commercial finance roles such as business partners and financial analysts [17].

However, the transformation brings significant risks. A notable trend driven by automation is the reduction in graduate-level hiring by major firms, raising concerns about potential shortages of experienced mid-level professionals that could impact future business operations and growth [18]. The accounting sector’s talent pipeline may be fundamentally disrupted if entry-level positions continue to disappear, creating a hollowed-out profession unable to develop the next generation of senior practitioners.

The adoption of AI tools among Irish workers has grown by 27% in the past year, according to Microsoft’s Work Trend Index for 2025 [19]. More than half of workers see AI skills as a career catalyst, with 41% saying it helps them work smarter and a similar proportion believing it will accelerate their careers [20]. Yet access remains deeply unequal; 91% of board-level executives report using AI regularly compared to just 39% of non-managerial staff [21].

This digital divide extends across demographic lines. Just 47% of female workers report using AI tools compared with 63% of men, whilst only 55% of Gen Z staff use AI at work, lower than younger millennials (62%), older millennials (59%), and Gen X workers (47%) [22]. For organisations, this represents both a risk and an opportunity. Companies that provide comprehensive AI training across all levels of the workforce will develop significant competitive advantages, whilst those that fail to democratise access to these tools risk exacerbating existing inequalities and limiting innovation.

Sectoral winners and losers

The impact of technological change and economic uncertainty varies dramatically across sectors. Life sciences and engineering roles remain stable, driven largely by increased automation and compliance requirements [23]. Automation manufacturing has grown significantly, with a 20% increase since the previous year, leading to strong demand for specialised automation engineers [24].

Financial services have maintained consistent hiring across funds, insurance, and banking sectors, with employers particularly focused on roles requiring compliance expertise, including anti-money laundering and Know Your Customer functions [25]. Relationship management positions also remain highly sought after due to the ongoing focus on client retention and service excellence [26].

By contrast, the technology sector presents a more nuanced picture. Whilst recruitment remains robust for cybersecurity specialists, driven by heightened regulatory requirements such as NIS2 and DORA, contract hiring among larger multinational firms has slowed, influenced by tighter cost controls prompting a shift towards permanent positions or offshore staffing solutions [27]. Data from Indeed shows IT operations and helpdesk postings down almost 30% from February 2020 levels [28].

The construction sector faces perhaps the most acute challenges, with persistent shortages of skilled professionals, especially quantity surveyors and project planners [29]. These gaps are amplified by Ireland’s severe housing shortage, procurement bottlenecks, and intensified competition from higher-paying European markets, which continue to attract Irish talent abroad [30].

Talent inflow

Ireland’s reputation as a stable, open economy is fuelling a wave of international talent inflows, particularly from the United States and the Middle East. Matt Fitzpatrick, Executive Director at Marks Sattin Ireland, notes that “there’s been a noticeable rise in interest from the Middle East over the past year, and recently we’ve seen a sharp uptick in U.S. candidates, some leveraging Irish ancestry to make the move” [31].

For Marks Sattin, overseas candidates, including Irish returners, made up over 40% of placements in Ireland in early 2025 [32]. This represents a strategic response to global volatility, with Ireland increasingly perceived as a geopolitical safe haven. However, international interest in Irish jobs dropped slightly between January and April 2025 to 12.3%, down from 14.8% in December 2024, according to Indeed data [33].

The influx creates challenges around remuneration. Ireland’s salary levels remain modest compared to major financial hubs like London or New York, aligning more closely with Amsterdam in terms of compensation [34]. Other European nations such as Germany, Belgium, and Luxembourg often present more generous salary offers without necessarily balancing this with lower tax burdens or living costs [35]. For new international entrants, the Irish market poses a necessary trade-off between earnings and overall lifestyle.

Yet Ireland’s attractiveness extends beyond pay. The country boasts a high standard of living, accessible healthcare, excellent schools, and a progressive work culture. The tight labour market continues to support robust wage growth, with year-on-year posted wage growth measured at 4.6% in December 2024, decently above the euro area average of 3.3% [36]. With Irish inflation falling to 1% or less in recent months, workers are seeing substantial real-terms pay growth [37].

Strategic imperatives

The employment landscape facing Irish organisations demands fundamental shifts in strategy. The low level of alignment between HR priorities (which remain focused on talent management, leadership development, and employee experience) and broader organisational priorities around cost management, digitalisation, and productivity suggests a concerning disconnect. As the CIPD’s HR Practices in Ireland report notes, “the profession needs to invest more in looking into the business and to better connect its work with key business challenges” [38].

Four in five HR professionals reported an increase in the impact of their profession in the past 12 months [39]. Yet areas where fewer perceive that the profession brings added value include sustainability (77%) and championing a people-centred approach to technology and AI (63%) [40]. The response to how HR champions a people-centred approach to technology has fluctuated significantly, from 77% in 2023, declining to 53% in 2024, and rising to 63% in 2025 [41]. This volatility suggests the profession is still finding its footing in navigating technological transformation.

Organisations must also grapple with profound shifts in employee expectations and behaviour. A record 38% of Irish workers moved roles in 2025, up from 23% the previous year and 19% in 2023 [42]. This marks Ireland’s most volatile labour market in three years, coinciding with a 13% fall in workplace happiness to 65% [43]. Whilst burnout levels have improved to a three-year low of 39%, 30% of workers plan to look for more flexibility in the coming year [44].

The persistence of remote and hybrid work, despite organisational efforts to increase office attendance, reflects this demand for flexibility. Around 2.6% of all searches for Irish job postings contained remote or hybrid keywords as of the end of December 2024, similar to levels prevailing since 2022 and up around tenfold on pre-pandemic levels [45]. Professional and tech categories including arts and entertainment (50%), media and communications (43%), insurance (43%), and software development (41%) show the highest shares of remote and hybrid postings [46].

Moving forward

The Irish labour market has entered a period of profound uncertainty. The pharmaceutical industry, a pillar of Ireland’s tax base, faces possible headwinds from proposed Trump tariffs, with significant implications for both employment and fiscal stability. More broadly, given Ireland’s trade dependency and reliance on the multinational sector, any changes to US trade or tax policies could potentially harm the Irish economy.

Yet the fundamentals remain strong. The employment rate for people aged 15-64 years reached 74.7% in the first quarter of 2025, up from 73.8% a year earlier [47]. The number of people in employment rose by 89,900 or 3.3% to 2,794,100 [48]. The unemployment rate stood at 4.3%, not far from the 4% rate generally considered nearing full employment in Ireland [49].

For organisational leaders, the challenge is navigating this complex landscape whilst building resilient, adaptable workforces. This requires moving beyond traditional approaches to talent management and embracing more fundamental questions about how work is structured, where it is performed, and what skills will prove essential. The organisations that thrive will be those that democratise access to AI tools, embrace geographic flexibility, invest in comprehensive upskilling programmes, and maintain the agility to respond to continued volatility.

Sources

[28] https://www.hiringlab.org/uk/blog/2025/01/28/indeed-2025-ireland-jobs-and-hiring-trends-report/

[31] https://www.markssattin.co.uk/general/2025-8/ireland-s-talent-boom

[32] https://www.markssattin.co.uk/general/2025-8/ireland-s-talent-boom

[34] https://www.markssattin.co.uk/general/2025-8/ireland-s-talent-boom

[35] https://www.markssattin.co.uk/general/2025-8/ireland-s-talent-boom

[36] https://www.hiringlab.org/uk/blog/2025/01/28/indeed-2025-ireland-jobs-and-hiring-trends-report/

[37] https://www.hiringlab.org/uk/blog/2025/01/28/indeed-2025-ireland-jobs-and-hiring-trends-report/

[45] https://www.hiringlab.org/uk/blog/2025/01/28/indeed-2025-ireland-jobs-and-hiring-trends-report/

[46] https://www.hiringlab.org/uk/blog/2025/01/28/indeed-2025-ireland-jobs-and-hiring-trends-report/

[47] https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-lfs/labourforcesurveyquarter12025/keyfindings/

[48] https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-lfs/labourforcesurveyquarter12025/keyfindings/

[49] https://www.hiringlab.org/uk/blog/2025/01/28/indeed-2025-ireland-jobs-and-hiring-trends-report/

When Rachel Reeves delivered her second budget as UK chancellor on Wednesday, 26 November, the reverberations were felt far beyond Westminster. For Ireland, the implications of Reeves’ fiscal choices strike at the heart of shared economic ecosystems, from Northern Ireland’s family farms to Dublin’s financial services sector, and from betting shops in border towns to the calculations of multinational corporations weighing where to base their European operations.

The budget arrived amid what observers have characterised as one of the most chaotic periods in recent British political memory. As Dominic McGrath noted in The Business Post, “the lead-up saw every twist, turn and tax policy leaked or briefed out, while a bait-and-switch approach to an income tax U-turn left bond markets flustered and allies confused” [1]. The resulting package — £26 billion in tax increases, though less than the feared £40 billion — represents not merely a set of fiscal adjustments but a fundamental recalibration of the UK’s economic direction with profound cross-border consequences.

Northern Ireland

For Northern Ireland, the budget’s impact feels particularly acute. Chartered Accountants Ireland, representing over 5,500 members in the region, has voiced deep concern about proposed changes to agricultural property relief and business property relief, set to take effect in April 2026. As Leontia Doran, UK Tax Manager with the organisation, explained: “These changes are disappointing and particularly damaging in Northern Ireland where family-owned businesses and farms are the heartbeat of the economy. Eighty-four per cent of businesses here are either family owned or managed, and they support over 325,000 jobs.” [2]

The proposed changes have already sent shockwaves through Northern Ireland’s farming community. Doran argues that “a carve-out is needed to exempt genuine farming activity and protect family-owned businesses in NI,” suggesting the government could have included a threshold to continue providing smaller farms and businesses with full relief if their farming or business assets comprise a minimum proportion of their overall estate [3]. The absence of such provisions, combined with a lack of transitional measures to protect older taxpayers, threatens to fundamentally alter the economic landscape of a region where family enterprises form the bedrock of employment and community life.

Both sides of the border

Beyond the farm gate, Reeves’ decision to freeze income tax and National Insurance Contributions thresholds until 2031 presents another concern for workers on both sides of the border. This continuation of the freeze, Doran noted, “is having an ever-increasing effect on people’s net after tax income and is expected to bring many more taxpayers into the higher rate tax bracket by 2030/31, a phenomenon known as ‘fiscal drag'” [4]. The policy risks creating a stagnant labour market whilst reducing household spending power, effects that will inevitably spill over into cross-border commerce and consumer behaviour.

Perhaps most significantly for Ireland’s strategic interests, Chartered Accountants Ireland has been campaigning for a reduced rate of corporation tax in Northern Ireland, more closely aligned with rates across the rest of the island. As Doran concluded: “A reduction in this rate would in the longer run ultimately increase tax take by driving the creation of better jobs and incentivising business growth. Add to this higher value FDI and the gains for Northern Ireland would set a real benchmark for what can be achieved with ambitious tax policies” [5]. The budget’s silence on this issue represents a missed opportunity to unlock the region’s potential, particularly its unique dual market access.

The business community’s response to the budget reveals the complex calculus facing firms operating across both jurisdictions. Noel McDonald and Donata Berger, founders of organic food company Biona, articulated a fundamental tension in how businesses are perceived and treated. McDonald argued: “The message that I would like to see coming out from government is that business is the only organisation in the country, in the economy, that generates wealth. Everything else is about spending the wealth, but the business is the only thing that generates wealth.” [6]

Berger pointed to the practical consequences of Labour’s approach: “This National Insurance contribution is massive for supermarkets. What does it lead to? People are cutting down on staff. They’re rationalising. Automation will be driven hugely. They should be doing more to support businesses. I think punishing businesses to the point that they have to shut down, and then you have a lot of people unemployed, that doesn’t move the country forward.” [7]

Irish companies with UK ops

For Ireland-headquartered firms with significant UK operations, the budget presented a mixed picture. Dalton Philips, chief executive of Greencore, struck a relatively sanguine note despite acknowledging challenges: “We’ve dealt with heavy levels of inflation. If you think through 2022/23 the level of inflation was materially greater than what we’re having to face now, and we were able to manage through that. We’ve got structural tailwinds in our business” [8]. His confidence rests on trends towards premiumisation, convenience, and eating in, all underpinned by UK population growth of approximately one per cent annually.

Yet the cumulative burden of fiscal tightening cannot be dismissed. Neil Hosty, chief executive of Fexco, acknowledged: “We’ve experienced it as an employer, for sure, we try to support our employees, to make sure that we’re keeping pace with wage inflation and trying to help them offset price inflation. National Insurance last year would be great example. And sometimes you just have to absorb those” [9]. His longer-term optimism about Britain’s entrepreneurial spirit cannot entirely mask the short-term pain his comments reveal.

Betting big?

The gambling sector, dominated by Irish firms like Flutter and BoyleSports, faced particularly sharp changes. From April 2026, remote gaming duty will increase from 21 per cent to 40 per cent, whilst a new tax rate of 25 per cent for general bets made remotely will come into force in April 2027 [10]. Flutter announced the changes would hit adjusted earnings by $860 million over two years, though the company believes it can mitigate costs and potentially increase market share as smaller competitors struggle. [11]

BoyleSports chief executive Vlad Kaltenieks had previously warned that tax increases would create “a more difficult environment” for the firm’s £100 million investment in new retail stores across Britain [12]. His concerns proved partially justified, though the decision to spare high-street bookmakers from additional levies offered some relief. Kevin Harrington, Flutter’s chief executive for UK and Ireland, called the changes “very disappointing,” warning they would “hand a big win to illegal, unlicensed gambling operators who will become more competitive overnight.” [13]

Grand narrative

From a strategic perspective, Cillian Molloy, policy manager at the British Irish Chamber of Commerce, articulated what many business leaders were thinking: “For that partnership to flourish, the chamber believes the budget must prioritise policies that restore economic stability, promote business confidence, and deepen trading links with our nearest neighbours and our largest market, the European Union. Businesses on both sides of the Irish Sea need predictable regulatory and tax frameworks.” [14]

McGrath’s assessment of the budget itself was measured but pointed: “Rather than a Mario Draghi-esque ‘whatever it takes’ moment for Reeves, it was hard to escape a sense it came closer to ‘will this do?'” [15] He noted that despite creating a £22 billion fiscal buffer, “UK finances still remain highly susceptible to economic shocks,” with borrowing remaining high for the next three years and back-loaded tax rises and spending curbs only arriving at the end of the decade — conveniently timed around the next election. [16]

Advantage Ireland

For Ireland, one unexpected silver lining emerged from Britain’s fiscal troubles. Alan Murray, a tax partner at Forvis Mazars, suggested that “Ireland now has a ‘massive advantage’ over the UK in attracting ultra-high-net-worth individuals” following Keir Starmer’s decision to scrap the UK’s non-dom regime [17]. However, Murray warned that chronic infrastructure problems — housing shortages, inadequate transport links, school capacity — prevent Ireland from capitalising on this opportunity. As he put it: “If you leave the city centre of Dublin at 4pm on a Friday, and you try and get to Dublin Airport, good luck to you.” [18]

Implications

The broader implications of Reeves’ budget extend beyond immediate fiscal impacts. Elliott Jordan-Doak, a senior economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, offered a sobering assessment: “Despite the positive spin from the chancellor today, the fiscal outlook remains perilous. The path of least resistance will continue to be to borrow more in the short-term and backload corrective action, until the bond market forces a change. Accordingly, we expect gilt yields to remain elevated.” [19]

For Irish business leaders and policymakers watching from across the Irish Sea, the message is that Britain’s economic instability represents both challenge and opportunity. The challenge lies in navigating the immediate impacts of tax rises, threshold freezes, and sectoral levies on firms operating in both markets. The opportunity lies in positioning Ireland as a stable, attractive alternative for investment and talent, if only the infrastructure can be put in place to support it.

As McGrath concluded, “it’s hard not to conclude that Reeves may only have pushed her problems onto the next budget” [20]. For Ireland, that means continued uncertainty about its largest trading partner’s direction, ongoing concerns about Northern Ireland’s economic trajectory, and difficult questions about how best to press home competitive advantages whilst maintaining the close bilateral relationship that has historically served both nations well. In an interconnected economy, no budget is truly domestic, and Britain’s fiscal choices will continue to shape Ireland’s economic landscape.

Sources

[2] https://www.charteredaccountants.ie/News/chartered-accountants-ireland-reacts-to-uk-budget-2025

[3] https://www.charteredaccountants.ie/News/chartered-accountants-ireland-reacts-to-uk-budget-2025

[4] https://www.charteredaccountants.ie/News/chartered-accountants-ireland-reacts-to-uk-budget-2025

[5] https://www.charteredaccountants.ie/News/chartered-accountants-ireland-reacts-to-uk-budget-2025

[11] https://www.businesspost.ie/markets/flutter-uk-gambling-tax-will-cost-us-860-million/

[13] https://www.businesspost.ie/markets/flutter-uk-gambling-tax-will-cost-us-860-million/

The autumn leaves have barely finished falling when the first tinsel appears in shop windows, and suddenly we’re hurtling toward December 25th at alarming speed. For most of us, this creates a peculiar cognitive dissonance. Our calendars fill with deadlines and year-end deliverables whilst our minds drift toward holiday plans, gift lists, and the promise of time off. All the while we’re left wondering how we can navigate this uniquely challenging period without compromising our professional responsibilities or our sanity.

The phenomenon of the pre-Christmas productivity slump is well documented. Research by the HR analytics group Peakon found that up to 57 per cent of British workers admitted they had mentally checked out by the third week of December, with some engaging in online shopping, others planning Christmas Day festivities, and nearly 20 per cent leaving work earlier than usual [1]. What’s particularly striking is that younger workers tend to disengage even earlier. More than a third of those aged between 18 and 34 reported festive distractions cutting their productivity by mid-December [2].

This isn’t merely a British affliction. In the United States, most employees expected to lose focus at work by 16 December, whilst German workers followed a day or so later [3]. The pattern is clear, as the year draws to a close, our collective attention span contracts, regardless of how many urgent emails populate our inboxes. In Ireland, things are no different.

Pressures

What makes the pre-Christmas period particularly vexing is that it combines multiple sources of stress into a perfect storm of distraction. As Benjamin Laker, a university professor who writes about leadership, observed in Forbes, “this time of year is often laden with social commitments, family responsibilities, and the general hustle and bustle that comes with preparing for the holidays” [4]. These aren’t trivial distractions that can be dismissed with willpower alone. They represent legitimate demands on our time, energy, and emotional resources.

The workplace itself often contributes to the chaos. Many organisations experience what Jeff Maggs of Brunner agency described as the “December dip” [5], a predictable downturn in productivity that coincides with reduced working hours, employees taking annual leave, and the general anticipation of the holiday break. For some industries, however, December brings the opposite problem of an increase in workload as everyone scrambles to complete projects before the year ends. Suddenly workers must accomplish the same amount (or more) in less time, whilst simultaneously managing heightened personal obligations.

The financial pressures of the season compound these difficulties. Gift-buying, travel arrangements, and the expectation of hosting or attending multiple social events all require resources that may already be stretched thin. Economic worries have made recent holiday seasons particularly stressful for many people [6]. When your budget is already under strain, the pressure to maintain festive appearances whilst meeting professional obligations becomes considerably more acute.

Peak performance myths

Perhaps the first step toward managing this period effectively is abandoning the fiction that we can maintain peak productivity throughout December whilst simultaneously embracing the festive season. The reality is that something has to give, and acknowledging this is more pragmatic than defeatist.

Strategic planning becomes essential. Rather than attempting to power through with sheer determination, successful navigation of the pre-Christmas period requires what Laker described as “a balance of good planning, effective time management, and self-care” [7]. This means establishing clear and realistic goals for the holiday season, understanding your actual capacity rather than your aspirational one, and setting achievable objectives that account for the genuine distractions you’ll face.

Breaking larger goals into smaller, manageable tasks proves particularly valuable during this period. Laker explained that this approach “makes the larger goal seem less daunting and allows for a sense of accomplishment as each smaller task is completed” [8]. When your attention span is fractured by competing demands, the ability to point to concrete progress, however modest, becomes psychologically crucial.

Time management tools can be particularly useful in December. Calendars and to-do lists help organise your time efficiently, but the key is prioritising ruthlessly based on importance and deadlines. As Laker advised, “remember, not everything needs to be done immediately” [9]. The Pomodoro Technique, which involves working in focused bursts followed by short breaks, can be especially effective when your concentration is under siege from festive distractions.

Setting boundaries

One of the most challenging aspects of the pre-Christmas period is managing the boundary between work and personal life, which becomes peculiarly porous at this time of year. The expectation to be simultaneously productive at work and fully engaged with holiday preparations creates what amounts to a double shift for many of us.

Setting clear boundaries requires communication with both family and colleagues. Laker noted it’s “essential to communicate your availability to family and colleagues, making it clear when you will be working and when you will be available for holiday activities” [10]. This clear demarcation helps manage expectations and reduces the guilt that often accompanies the attempt to juggle work and personal commitments.