1. Modern Leadership: Bridging Tradition and Innovation

Tokyo, a city where centuries-old temples stand alongside cutting-edge skyscrapers, exemplifies the merging of tradition with innovation. It paints a vivid picture of today’s leadership paradigm, where the challenge is to preserve age-old wisdom while embracing the agility demanded by modern times.

Take the example of Indra Nooyi, the former CEO of PepsiCo. Her approach was not just anchored in advanced business strategies but was deeply influenced by her roots and traditional values. By penning personal notes to the parents of her executives, Nooyi demonstrated a unique synthesis of cultural respect and contemporary leadership—suggesting that the two aren’t mutually exclusive but can indeed complement each other.

Now, more than ever, leadership encompasses a broader range of skills and qualities. Cross-cultural understanding, for instance, has emerged as a pivotal asset. It’s not just about an American entrepreneur being fluent in Mandarin but understanding and navigating the nuances of global markets, appreciating cultural subtleties, and forging meaningful partnerships across borders.

Ethical leadership is another domain gaining prominence. Companies like Patagonia, led by visionaries like Rose Marcario in the past, have shown that responsible governance isn’t just about ticking corporate responsibility boxes. In fact, Patagonia has committed to donating 1% of its total sales to environmental organisations through its “1% for the Planet” initiative, amounting to over $89 million in donations since the program’s inception. This move is a testament to genuinely embedding sustainability and transparency into the core business strategy, setting a gold standard for other enterprises to emulate.

In places of innovation like Silicon Valley, the very definition of leadership is evolving. It’s not confined to boardrooms or dictated by tenure. Here, a brilliant idea can propel a young developer into a leadership position, proving that age is becoming less of a determinant. Instead, adaptability, innovative thinking, and a relentless drive are becoming the hallmarks of modern leaders.

This shift in leadership dynamics extends beyond the corporate sphere and into global governance. While individual leaders may have their strategies and legacies debated, certain qualities are universally revered. Steadfastness, principled decision-making, and genuine empathy are essential traits for effective leadership in our interconnected age.

In today’s organisational landscape, leadership is omnipresent, transcending hierarchies. Firms like Google underscore this, promoting a culture where leadership emerges from collaborative efforts, proactive initiatives, and shared responsibilities. As the business world becomes increasingly complex, understanding and adopting these multifaceted leadership approaches isn’t just commendable; it’s imperative for sustainable success.

2. Leadership: A Blend of Nature, Nurture, and Adaptation

In every organisation, each individual brings unique skills and perspectives. While each member’s contribution is vital, the leader, much like a conductor, brings together these diverse talents to create a cohesive and effective outcome. Today’s leaders harness their natural abilities and continually refine and develop new skills to lead effectively.

Leadership is a synergy of inherent traits and cultivated abilities at its core. Determination, decisiveness, and vision may be innate for many, but skills such as emotional intelligence underline the constant evolution and adaptation that the modern leadership landscape demands. The journey of Ratan Tata, who transformed the Tata Group into a global conglomerate, exemplifies this balance. His leadership displayed a mix of inherited business acumen and learned skills, showcasing the essential interplay of nature and nurture in leadership.

In our fast-changing corporate world, leaning solely on inherent strengths or past achievements doesn’t suffice. Leaders like Isabelle Kocher, the former CEO of Engie, one of the world’s largest utility companies, recognised the importance of adaptability and sustainability in modern leadership. Under her direction, Engie embarked on a radical transformation, moving away from fossil fuels and heavily investing in renewable energy sources and infrastructure. This bold shift was not just a business strategy but a reflection of Kocher’s vision for a sustainable future. She spearheaded efforts to divest from coal operations and led Engie to invest in innovative renewable energy projects, embracing the future of clean energy. Effective communication played a crucial role in this transition. Kocher was adept at relaying information and conveying her passion, vision, and purpose to her team at Engie and the broader public, emphasising the company’s commitment to a sustainable and environmentally responsible future.

Diverse approaches to leadership also paint the modern landscape. While some leaders may naturally exude authority, others bring forward the strength of collaboration, collective achievements, and mutual respect. Leadership in the realm of the arts, for instance, as demonstrated by Theaster Gates—a social practice installation artist—shows how leadership can transcend corporate and political boundaries, making waves in cultural and community contexts.

Leadership today is not just about a title or a position. It’s a harmonious blend of what one is born with and what one learns and adopts, all tuned to the evolving needs of organisations and societies. Two prominent leadership styles that have gained traction in this context are ‘laissez-faire’ and ‘transformational’ leadership.

The laissez-faire style, which is derived from the French term meaning to “let go”, allows team members significant autonomy in their work. Leaders like Steve Jobs and Steven Bartlett are often associated with this style. They trusted in their teams’ inherent creativity and drive, intervening only when necessary. Such an approach has its merits in industries that thrive on innovation and where the creative freedom of individuals is paramount.

On the other hand, transformational leadership, as embodied by figures like Richard Branson, inspires and motivates team members to exceed their own expectations and achieve a collective vision. These leaders are proactive, continuously challenging the status quo and instigating change to better the organisation. They foster an environment where both the leader and the team support each other’s growth and transformation.

Both these styles emphasise the shift in norms surrounding leadership today. It’s no longer about just directing or managing but about inspiring, trusting, and continuously evolving to meet the ever-changing demands of the modern world.

3. Shaping the Future: The Role of Proactive Leadership

Proactive leadership focuses on more than just addressing current challenges; it’s about actively planning and influencing the future. While entrepreneurs like Elon Musk are often highlighted, digging deeper and understanding the foundational principles that enable such forward-thinking actions is important.

One key concept from organisational psychology is ‘Psychological Safety’. Introduced by Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson, it describes an environment where team members feel secure in taking risks and expressing their ideas without fear of reprimand. Successful teams, like those at Google, have pinpointed Psychological Safety as a driving factor. When leaders cultivate this safe space, they express organisational values and encourage a culture where innovation can flourish.

This atmosphere of trust and openness is especially crucial in today’s interconnected world, where leadership actions are constantly scrutinised. Every decision and every mistake is magnified in the digital age. It underscores the idea that ethical behaviour isn’t just a commendable attribute—it’s vital. Leaders who prioritise psychological safety invariably pave the way for ethical leadership. In this scenario, proactive leadership revolves around upholding transparency and ensuring that decision-making is always rooted in strong ethics, allowing team members to communicate openly and act with integrity.

However, challenges such as persistent gender biases remind us that there’s still work to be done. Effective leadership recognises such biases and takes deliberate steps to address and overcome them, ensuring that potential is recognised and nurtured regardless of gender or background. For instance, the often-discussed gender pay gap shows that women, on average, earn less than men in nearly every single occupation for which there is sufficient earnings data. This reflects a systemic inequality and can damage psychological safety, as it conveys an implicit message that women’s contributions are less valuable. Proactive leadership recognises such biases and actively works to address and correct them, ensuring that every team member feels valued and heard. This atmosphere of trust and openness directly feeds into the broader principle of psychological safety, where individuals can communicate openly without fear.

In conclusion, proactive leadership is about foresight and action. It means navigating the present while laying strong foundations for the future, driven by a combination of psychological understanding and ethical commitment. Today’s leaders don’t just ride the waves—they help create them.

4. Crafting Your Leadership Path

Leadership is a unique journey, blending inherent qualities, acquired skills, and external influences. Apple’s co-founder, Steve Jobs, advocated for pursuing passions and trusting one’s instincts. However, the leadership voyage extends beyond instinct. Like those by Daniel Goleman on emotional intelligence, ground-breaking studies highlight self-awareness as a keystone of effective leadership. Such understanding aids leaders in harnessing their strengths and addressing their vulnerabilities.

Adaptability is pivotal in the current age of rapid technological and societal changes. Management theories such as the Situational Leadership Model, developed by Hersey and Blanchard, emphasise that leaders must adjust their style based on the task and individual’s maturity. So, while the world moves quickly, aligning personal and organisational values ensures that leadership remains authentic and relevant.

Every leadership story is unique and shaped by personal aspirations, experiences, and trials. Recognising this, there’s a need to move beyond one-size-fits-all strategies. Customised leadership plans, tailored to individual paths and goals, prove more effective than generic formulas. A principle of economics, the Theory of Comparative Advantage, posits that individuals or entities should capitalise on their strengths. In the leadership context, this underscores focusing on one’s unique capabilities and value propositions. Furthermore, leaders aren’t isolated figures; they operate within complex organisational ecosystems. Just as a sailor must consider the sea’s currents and weather patterns, leaders must understand their organisational cultures. An environment fostering open dialogue, feedback, and continuous learning can catalyse a leader’s evolution. Conversely, restrictive cultures might pose challenges. But in both contexts, understanding and adeptly navigating these nuances differentiates good leaders from great ones.

In essence, leadership is not a linear path but a dynamic journey. It combines introspection, adaptation, and understanding of the larger organisational landscape. As the saying goes, it’s not just about the destination but the journey and how one travels it.

5. Visionaries to Tomorrow’s Leaders

Great leaders throughout history have consistently displayed adaptability, innovation, and a commitment to mentoring the next generation. Larry Page’s leadership at Google exemplified this. Rather than solely focusing on ideas, he emphasised nurturing talent, most notably by mentoring Sundar Pichai. This approach underscored the belief that a true leader’s legacy is in empowering successors. Apple’s resilience and ability to reinvent itself embody the “falling forward” concept — transforming challenges into opportunities. Amazon’s success story is a testament to adaptability, echoing Bruce Lee’s advice to be “like water,” — flexible, yet forceful. In the tech realm, Netflix’s pioneering use of AI and Microsoft’s emphasis on cloud computing under Satya Nadella highlight the importance of forward-thinking innovation, drawing parallels to historical visionaries like Tesla and Edison.

6. Cultural Harmony: Crafting the Future of Leadership

Satya Nadella’s transformative journey at Microsoft exemplifies the essence of a growth mindset, teaching us that true success isn’t solely about beginnings but rather the directions we’re willing to explore. With its relentless drive to innovate, Tesla embodies the spirit of pioneers who are never content with the status quo. Adobe’s culture of valuing feedback and continuous improvement is a testament to the belief that “iron sharpens iron,” highlighting the power of collective growth and learning. Similarly, Spotify’s commitment to inclusivity is not just a nod to diversity but a clear indication that the future of leadership mirrors and celebrates the myriad voices of society.

In essence, these examples underline that the modern leadership paradigm thrives on adaptability, continuous growth, and cultural harmony, emphasising that the best leaders not only lead but also listen, learn, and reflect the diverse tapestry of our global community.

7. Nurturing Leadership: Strategies, Collaboration, and Vision

Margaret Heffernan’s concept of “wilful blindness” refers to the deliberate decision to ignore or avoid inconvenient facts or realities, even when they are readily apparent. It underscores the importance of leaders being vigilant, aware, and attentive, breaking from conformity to foresee and address challenges. Salesforce’s culture, which champions innovation and disruption, mirrors the economic principle of ‘creative destruction’ proposed by economist Joseph Schumpeter, where innovative methods and ideas replace old ways of doing things. Reflecting on the management theories of Peter Drucker, he emphasised that “Management is doing things right; leadership is doing the right things.” As emerging leaders design their journey, frameworks, like Amazon’s leadership principles, serve as contemporary iterations of timeless navigational tools — guiding leaders both on well-trodden paths and ventures into the unknown.

8. Future Leadership: Charting New Waters with Timeless Principles

Drawing from Charles Darwin’s insights, it’s not the strongest species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the most responsive to change. In the realm of leadership, this rings especially true. Traditional hierarchical models are yielding to a more collaborative and adaptive approach. The dawn of AI and the intricate dance of globalisation echo the words of economist John Maynard Keynes, emphasising the need to be versatile in the face of “animal spirits” or unpredictable elements in markets. Cybersecurity concerns today might parallel the challenges once posed by maritime pirates during the age of exploration, underscoring that while challenges evolve, the essence of leadership remains in navigating uncharted territories. Tomorrow’s leaders will not only ride the waves of technological change but also harness the diverse strengths of global teams and confront ethical quandaries in a deeply interconnected era guided by principles as old as leadership itself.

9. Leading Forward: Drawing from the Past, Shaping Tomorrow

Much like Rome, which wasn’t built in a day, leadership thrives on a foundation of age-old principles fused with modern foresight. This blend is reminiscent of the principles set forth by legendary strategist Sun Tzu in “The Art of War” – understanding the terrain, knowing oneself, and being fluid in response. Today’s urban jungles, from Tokyo to New York, encapsulate this harmony; they meld historical foundations with skyscrapers of ambition, symbolising the fusion of past wisdom with future vision. Leaders like Indra Nooyi exemplify this duality, resonating with the roots of ancient wisdom while spearheading an era of digital transformation. Leadership, therefore, isn’t a destination but an ongoing odyssey. Much like cities that reinvent while retaining their essence, leaders must be perpetual pioneers with an eye on the horizon and feet grounded in enduring values.

More on Trust

The Importance of Trust article by Shay Dalton

Elite Team Cohesion article by Jonny Cooper

Leadership in Focus: Foundations and the Path Forward article by Shay Dalton

The Importance of Ethics article by Shay Dalton

“Empowering” Workers is More Than a Catchy Phrase article by Shay Dalton

Introduction

Are humanities subjects – and humanities students – doomed? – 1% Extra Article – Rob Darke

“We should cheer decline of humanities degrees.”

So read the headline of a piece by Emma Duncan in The Times. Duncan, who notably studied Politics and Economics at Oxford, thinks that the decline in the number of students enrolling in humanities degrees is a societal positive. And her reasoning is sound. She says that the humanities fail to engender in their students sufficient practical skills to be both employable once they graduate, and able to thrive once they’re part of the workforce. The lack of skills today’s humanities graduates are instilled with and the subsequent lack of employment they are able to find as a result is, she says, why so many of today’s youth feel betrayed by their elders (she acknowledges that the bleak state of today’s housing market is also a factor) [1].

It’s a provocative piece, featuring statements like, “Literature is lovely stuff but it’s not a way to earn your bread,” that make one suspect it is deliberately so. It ignited a furious backlash from some corners of the internet and an equally furious backlash to the backlash from others. Such are the times we live in. But Duncan’s argument is nothing new. This debate has been raging since well before her own student days, though the merit of the arguments on each side does tend to depend on the context of the times in which the debate is taking place. The shifting state of employment rates and the in-vogue professional skills of the era are always going to have an impact.

In lieu of the topic’s re-emergence in the column circuit, it’s worth investigating what humanities offer, what students and employers want from a University education, and whether things are really moving in the right direction or the wrong one.

Humanities graduates: Penniless and unskilled?

Duncan argues that, “the people who are struggling are those in nice, fluffy jobs like publishing and the creative arts, and in the caring professions” [2]. Leaving caring aside, as this falls outside of the remit of humanities, Duncan is right that humanities and social science graduates are less well off than their STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) studying counterparts. But not by much.

STEM subjects are generally considered to be the crème de la crème of the practical degrees, all-but guaranteeing jobs in engineering, the finance sector, and a whole other heap of other lucrative industries. In the UK, however, where Duncan’s article was focused, STEM graduates earn on average £38,272 a year compared with humanities and social science graduates’ £35,360 [3]. The difference is useful cash in the pocket, most certainly, but not such a striking distance apart that STEM might be seen as the educational pinnacle while the humanities are dragged kicking and screaming to the pedagogical chopping block. Similarly in the US, for those aged 25-34, the unemployment rate of those with a humanities degree is 4%. For those with an engineering or business degree? A little more than 3% [4]. The vigour of the anti-humanities debate doesn’t seem to accurately reflect the marginality of these differentials.

Meanwhile, creative industries represent 5.6% of the UK’s GDP. The UK is the largest exporter of books in the world, in large part because of the strength of its publishing industry, and the creative industries are not only growing, but doing so at a faster rate than the economy as a whole [5]

In other words, the humanities are fine. Except, as is plainly apparent to anyone with skin in the game, that’s not really true. For all the detractors of Duncan’s article there is a reason that she wrote it, as well as something intrinsically recognisable in the notion at its core. While we may disagree that the decline in humanities is something worth cheering about, we do understand that the decline she so celebrates is real and worsening. The chances are that everyone reading this either knows a struggling humanities graduate or is one themselves.

A striking statistic from Duncan’s piece notes that, “Looking at higher education as an investment, the Institute for Fiscal Studies calculates that the return for men on a degree in economics and medicine is about £500,000, for English it is zero and for creative arts it is negative” [6]. Meanwhile, a recent report from the British Academy found that, “English Studies undergraduate students domiciled in England fell by 29% between 2012 and 2021” [7].

In the UK, there has been a 20% drop in students taking A-levels in English and a 15% decline in the arts [8]. Across the pond, a 2018 piece in the Atlantic found that the number of University History majors was “down about 45 percent from its 2007 peak, while the number of English majors has fallen by nearly half since the late 1990s” [9]. The piece also noted that the decline was “nearly as strong at schools where student debt is almost nonexistent, like Princeton University (down 28 percent) and the College of the Ozarks (down 44 percent).” In other words, rising tuition fees were not a factor, or at least not a strong one, in these numbers.

Why is it then that we’re seeing such a drop off in the number of students wanting to pursue a degree in the humanities, especially if the unemployment and starting salary figures are as closely aligned as the stats suggest?

What you should be doing…

In the aforementioned Atlantic article, the author, Benjamin Schmidt, notes that in the US there was a large-scale drop off in the number of humanities majors in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Schimidt argues that in the wake of the crisis, “students seem to have shifted their view of what they should be studying—in a largely misguided effort to enhance their chances on the job market” [10].

It’s not hard to understand why students would take such an action, or to think that a similar phenomenon is not underway in the wake of the twin crises of Covid and the cost of living. People know that the economy isn’t in great shape. They know that there are by an order of magnitude more graduates than ever before that they will soon be thrust into the real world to compete with. And they know – or think they know – that STEM subjects offer a level of security that more artistic ventures do not. In large part because that’s what people in positions of power have told them.

Put plainly, Schmidt argues that, “Students aren’t fleeing degrees with poor job prospects. They’re fleeing humanities and related fields specifically because they think they have poor job prospects” [11]. The gulf between the real and the speculative here is vital, and damaging. As already noted, Duncan is offering nothing new in her argument other than an oddly fatalistic sense of glee. STEM equals rich, humanities equals poor. That’s the basic conception underpinning most of the public’s school of thought on this matter. But as has already been shown, the numbers on that don’t quite stack up.

One might argue that to attribute such enormous declines in the numbers of humanities students purely to a collective attitudinal miscalculation is short-sighted. To counter that, it would be worth running an experiment in which students were able to sign up to a University where tuition was free and every first-year student had a guaranteed job lined up after education. Under these favourable circumstances, would students still be shunning the humanities or would it turn out that the cost and perceived lack of employability is the real problem? In such a scenario, given that we’ve already ruled out the cost being a key factor, we could say with some credibility that the perceived lack of employability a humanities degree offers was the number one reason for the declining numbers.

Thankfully, we don’t need to run such an experiment as these institutions already exist in the form of US military service academies. Students are granted free tuition and a guaranteed job within the US military upon graduation. And what do the numbers show? That at West Point, Annapolis and Colorado Springs, humanities majors were at roughly the same level in 2018 as they were in 2008 [12]. They were not affected by the colossal drop-offs in History and English majors that were noted earlier in the article.

Hard skills vs Soft skills

Why someone might think a STEM subject offers more than a humanities one is obvious. One offers hard skills, the other soft. STEM students have something tangible to show for their hard work, whether that’s in the form of lab skills or a mastery of a certain equipment. Stand that up against an English literature graduate and it may look like one has received much more bang for their buck through the University experience than the other. In this regard Duncan’s argument is entirely justified. Humanities students aren’t being taught hard, practical skills that set them up for the workplace. But a skill doesn’t have to be part to be practical. Indeed, to focus only on hard skills is to massively undervalue the soft skills one learns in the humanities and the vital role they play in a real-life professional environment. Not to mention, as we will show in a moment, what they offer fiscally.

Humanities students are taught to think critically, to engage with arguments and frame their own, to deal with people and empathise with a variety of viewpoints. In stark contrast to scientific or mathematical endeavours, it is far more important in the humanities to be able to step back and understand a range of possible answers, acknowledging the merits and flaws in each, than to arrive at a single, binary, immovable conclusion. As Karan Bilimoria, a member of the House of Lords and Chancellor of the University of Birmingham has said on the subject, “Anyone who thinks [humanities] subjects are of low value [doesn’t] know what they are talking about…They provide many transferable skills — analytical, communication, written — that help students to take on a range of jobs” [13].

James Cole, a software engineer in Bath, wrote to The Guardian in response to Sheffield Hallam’s announcement that they would be dropping their English Literature course. He agreed that English Literature offered something vital, even in his much more technical line of work, saying:

English Literature degrees teach criticism, a form of analysis that suits the workplace very well. What is the truth in a given situation, how does it tie into wider themes, and how can I best communicate that? Deep reading skills, mental organisation, patience. Studying STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) doesn’t develop these skills in the same way, and I should know because I also have an MPhil in computer science. Almost none of my colleagues have Humanities degrees, and it shows. [14]

Sheffield Hallam

Writing in the journal Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, Eliza F. Kent argues similarly, saying that: “the most important resource necessary to succeed in today’s competitive marketplace is a clear, eloquent, impassioned voice. The learning exercises at the foundation of excellent humanities-based education may appear to lack any utilitarian benefit, but their long-term effect is the development of each student’s individual voice, which is priceless” [15].

Soft skills: Money in the bank

In direct contrast to the many arguments that humanities are a one-way ticket to poverty, studies have shown that, due to their superior soft-skills, including diplomacy and people-management, humanities graduates often go on to find themselves in positions of leadership. 15% of all humanities graduates in the US go on to management positions (more than go into any other role) [16]. Meanwhile, a recent study of 1,700 people from 30 countries found that the majority of those in leadership positions had either a social sciences or humanities degree – this was especially true of leaders under 45 years of age [17]. Perhaps poverty does not this way lie after all.

The Future

What very few University degrees or workplaces are currently prepared for is the colossal impact AI is going to have on the kind of jobs that earn the most money, the kind that can be replaced, and the kind of skills students graduating into an AI-integrated workforce will need to be armed with. The likelihood that today’s students in any sphere are appropriately prepared for the wide scale changes ahead is slim. That’s probably doubly true for the aging and aged existing members of the workforce, who are generally likely to be less technologically articulate than their younger, tech-savvy counterparts.

Some people who do know about AI’s likely impact going forward are Brad Smith and Harry Shum, top-level executives at Microsoft who wrote in their book, The Future Computed, that:

As computers behave more like humans, the social sciences and humanities will become even more important. Languages, art, history, economics, ethics, philosophy, psychology and human development courses can teach critical, philosophical and ethics-based skills that will be instrumental in the development and management of AI solutions. [18]

Brad Smith and Harry Shum

Emma Duncan may be cheering on the demise of the humanities for the time being, then. But it seems like the soft-skilled graduates of tomorrow may end up having the last laugh.

Sources

[1] https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/we-should-cheer-decline-of-humanities-degrees-5pp6ksgmz

[2] https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/we-should-cheer-decline-of-humanities-degrees-5pp6ksgmz

[3] https://www.newstatesman.com/comment/2023/06/university-degrees-students-humanities-economics

[5] https://www.newstatesman.com/comment/2023/06/university-degrees-students-humanities-economics

[6] https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/we-should-cheer-decline-of-humanities-degrees-5pp6ksgmz

[9] https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/08/the-humanities-face-a-crisisof-confidence/567565/

[10] https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/08/the-humanities-face-a-crisisof-confidence/567565/

[11] https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/08/the-humanities-face-a-crisisof-confidence/567565/

[12] https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/08/the-humanities-face-a-crisisof-confidence/567565/

[13] https://www.khaleejtimes.com/long-reads/are-humanities-degrees-worthless

[15] Kent, E. F. (2012). What are you going to do with a degree in that?: Arguing for the humanities in an era of efficiency. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 11(3), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022212441769

[18] https://www.businessinsider.com/microsoft-president-says-tech-needs-liberal-arts-majors-2018-1

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, as its name suggests, focuses on the notorious father of the atomic bomb, J Robert Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer was recruited by the US government to lead the Manhattan Project during World War II. Oppenheimer and his team were in a frantic race of science against the Nazis for who could be the first to utilise newly discovered breakthroughs in fission to build an atomic bomb. The winner would wield more power than ever considered possible. They would be, as Oppenheimer himself famously noted, the “destroyer of worlds.”

Becoming death

Oppenheimer’s quote, originally from the Hindu scripture the Bhagavad Gita – in full, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds” – hints at the moral quandary at the centre of Nolan’s film and Oppenheimer’s legacy. What he and his team at Los Alamos achieved was an extraordinary feat of science, a rightly heralded achievement. As also noted in the film, Oppenheimer was not taking part in the project out of some twisted bloodlust, rather because he feared what would happen if the Nazis were able to create such a weapon first.

As it happened, the Nazis had surrendered by the time the bomb was complete. In August of 1945, the US government instead dropped bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. Estimates vary but it’s thought that over the two to four months following the bombings between 90,000 and 146,000 people were killed in Hiroshima and between 60,000 and 80,000 in Nagasaki, with roughly half of those deaths occurring on the first day [1]. Oppenheimer himself wrestled with the weight of what his creation had wrought for the remainder of his life. The question of whether dropping the bombs was a necessary act to bring the war to an end or a grotesque act of chest-puffing genocide continues to this day.

The Manhattan Project was not a business – though it did employ a whole town’s worth of scientists, engineers and their families. But the film is clear that the ethical implications of the work at hand went unconsidered until it was too late. While it may seem tenuous or trivialising to compare such an overtly destructive act to the ethical considerations of day-to-day business practice today, anyone who has read Patrick Radden-Keefe’s searing Empire of Pain [2] about the role of Purdue Pharma and the Sachler family in particular in generating the US opioid crisis, for which the death toll stands in the hundreds of thousands and counting, or has been paying close attention to the devastating climate impact wrought by Shell, Exxon, BP and the like over the past decades and its potential implications for the future of humanity, will recognise that ethics and business cannot be so easily separated. The ethical choices companies make can shape individual lives and entire worlds. It’s vital they’re taken seriously.

Business ethics

Business ethics refers to the standards for morally right and wrong conduct within a business. Businesses are, of course, held to account by law, but as we all know, there are slippery ways around the law. Something can be both legal and wholly unethical.

Business ethics are important for various reasons. As noted, in the most extreme cases, such as that of Purdue Pharma, the decision to downplay the addictiveness of their opioids contributed to or outright caused a deadly epidemic in the US. In less dramatic circumstances, some of the advantages of having a strong ethical practice in place are that it helps build customer trust (thus helping retain customers), improves employee behaviour, and positively impacts brand recognition. The numbers back that up.

Over half of U.S. consumers said they no longer buy from companies they perceive as unethical. On the flip side, three in 10 consumers will express support for ethical companies on social media [3]. A 2021 survey by Edelmen found that 71% of people believe that companies should be transparent and ethical [4]. Similarly a 2020 study on transparency from Label Insight and The Food Industry Association found that 81% of shoppers say transparency is important or extremely important to them [5].

Corporate executives surveyed by Deloitte, meanwhile, stated that the top reasons consumers lose trust in a consumer product company are that the brand is not open and transparent (90%), the brand is not meeting consumer environmental, social and governance expectations (84%), and the brand is engaging in greenwashing (82%) [6]. In case it wasn’t clear, then, ethics matter to consumers – which means they matter to business. And yet a 2018 Global Business Ethics Survey (GBES) found that fewer than one in four U.S. workers think their company has a “well-implemented” ethics program [7].

The businesses that are prioritising ethics, on the other hand, are reaping rewards.

Ethical profits

Ethisphere, an organisation that tracks the ethical conduct of the world’s largest companies, found that the businesses that qualified for its 2022 list of most ethical companies outperformed an index of similar large cap companies by 24.6 percent overall [8]. The Institute of Business Ethics similarly found that companies with high ethical standards are 10.7% more profitable than those without [9]. Honorees on the 2021 list of the World’s Most Ethical Companies outperformed the Large Cap Index by 10.5 percent over a three year period [10].

Not only do ethical companies make money, unethical ones lose it. 22% of cases examined in the 2018 Global Study on Occupational Fraud and Abuse cost the victim organisation $1 million or more [11]. And there are plenty of unethical companies who crashed and burned in a far more dramatic fashion.

Enron

Perhaps the most striking fall from grace was Enron, whose trading price plummeted to a level in accordance with its ethical standards in December of 2001. At the company’s peak, it had been trading at $90.75. Before filing for bankruptcy, its price was $0.26 [12]. For years Enron had been fooling regulators with fake holdings and off-the-books accounting practices while hiding its eye-watering levels of debt from investors and creditors. From 2004 to 2012, the company was forced to pay more than $21.8 billion to its creditors. Various high-level employees ended up behind bars.

Enron is the high-water mark for unethical disintegration. But there are plenty of moral and ethical quandaries for today’s mega-corporations to take on as well.

Ethics today

In the age of data, corporations, especially social media giants like Meta, have a huge ethical responsibility regarding their clients’ data. Extremely sensitive personal information is loaded into these sites on little more than an understanding of good faith on the consumers’ part. How that data is being used (or misused) by these companies is one of the defining discussion points of the age. That’s not to mention the targeting of ads and its potential detrimental impact, especially on the young. Rates of anxiety, depression and suicide in teen and tween girls, for example, surged from 2010, around about the time they first started getting iPhones [13]. A few years ago, Meta’s whistleblower, Frances Haugen, confirmed that the company’s internal data reflected that it was doing severe damage to the mental health of teenage girls. Despite having this information to hand, the company made no attempts to rectify the problem [14].

Meanwhile energy companies like BP, Shell and Exxon are being held to far greater scrutiny as the effects of their environmental wreckage are starting to play out more and more each year in the form of unprecedented spiking in temperatures, wildfires and floods. The company’s responsibility to its profit line is being put in conflict with its responsibility to the planet. Although record profits last year suggest that one is winning out over the other [15].

Companies like Google and Amazon, too, have ethical crises regarding their treatment of workers and data security. While their profits or position of dominance in their respective markets haven’t dropped, reputational damage has been done. Both companies will be working to try and keep the fallout to a minimum.

Implementing ethics

A company’s ethics start at the top. When management acts ethically, employees follow suit. Companies with strong ethical values tend to display their code of ethics publicly, allowing them to be held to account. Some key ways companies can create an ethical environment include conducting mandatory ethics training for all employees, integrating ethics with processes, creating a space where employees find it easy to raise concerns, clearly defining company values, fostering a culture of transparency, and aligning your incentive system with your company values [16].

The importance of ethics

Ethics are vital to an organisation’s longevity. Companies that choose to cut ethical corners may see short term gain, even thriving for decades, but when the chickens come home to roost, as they did for Enron, there’s no coming back. Climate change and issues around data-mining are placing greater scrutiny on companies who have historically been focused on profit-at-all-cost models detrimental to more macro struggles. In cut-throat business environments, morality and ethics can often be sidelined in pursuit of the bottom line. But as the numbers show, ethical companies are often rewarded by customers with repeat business, and reputational damage can prove irreversible.

Like the scientists at Los Alamos discovered, it’s possible to be so focused on innovation and achievement that you’re blinded to the ultimate consequences of your ambition. Sew the ethical seeds early so as not to be undone further down the line when your decisions play their course.

References

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atomic_bombings_of_Hiroshima_and_Nagasaki

[2] https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/612861/empire-of-pain-by-patrick-radden-keefe/

[4] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/importance-business-ethics-why-ethical-conduct-success-manelkar/

[5] https://www.business.com/articles/transparency-in-business/

[6] https://www.business.com/articles/transparency-in-business/

[8] https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/9424-business-ethical-behavior.html

[9] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/importance-business-ethics-why-ethical-conduct-success-manelkar/

[12] https://www.investopedia.com/updates/enron-scandal-summary/

[13] https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/11/facebooks-dangerous-experiment-teen-girls/620767/

Introduction

Welcome to the leadership paradox. Let’s start with a scenario. You joined your company many years ago, starting in a more junior role, where you proved your skill sets over and over. Maybe you were a born salesperson, maybe you were a master at client relations, maybe you were product focused, perhaps something else entirely. Regardless, with every task and every further year at the company, you demonstrated your value. As such, you were rewarded with a series of promotions. Eventually you found yourself in a management position, the leadership role you’d always wanted. Sounds great. All is well, right?

Not necessarily. Because once you’d reached this position, you discovered that the skills you’d demonstrated to get there weren’t needed anymore. You’d ceased to be the one selling; you’d ceased the one fronting the call; you’d ceased to be the one making decisions around specification. You might have still tried to do all those things, to involve yourself heavily and bring yourself back to the fore. Perhaps you rolled up your sleeves and said your management style was “hands-on”, justified your involvement in lower-level projects by saying you were a lead from the front type.

To do so is only natural. After all, you got to where you are by being an achiever, someone who not only got things done but prided themselves on being the one actively doing them. And this is where the paradox lies. Because the skills that served you so well and earned you your promotion might be the very same ones preventing you from succeeding in your new role.

This notion is distilled to its essence in the title of Marshall Goldsmith’s bestselling book: “What got you here won’t get you there” [1]. Being a thriving part of the workforce and being a leader are two entirely different things. The skills are not the same. To achieve, you need to be able to get the best out of yourself. To lead, you need to be able to get the best out of other people.

Oftentimes, newly promoted leaders try to continue as they were before. They want to get their hands dirty, to micro-manage and ensure that every aspect of a project is marked by their fingerprints. But micro-management is not the answer. As Jesse Sostrin PhD, Global Head of Leadership, Culture & Learning at Philips, puts it, leaders need to be “more essential and less involved.” He adds, “the difference between an effective leader and a super-sized individual contributor with a leader’s title is painfully evident” [2].

For many, the adjustment is difficult and can take time. If a leader is too eager to imprint themselves on every aspect of a project, not only is the leader likely to end up feeling overstretched (according to Gallup research, managers are 27% more likely than individual contributors to strongly agree they felt a lot of stress during their most recent workday [3]) but the project will suffer too. Staff will come to feel constrained and undervalued. They may not feel they have the opportunity to grow or express themselves fully. They will be less likely to try new and innovative ideas with someone breathing down their neck or dictating that they must service a single vision at all times rather than being allowed to bring themselves to the fore.

In other words, micro-management offers a whole lot of downsides in exchange for very few upsides. Sostrin proposes that a useful way for a manager to tell if they are taking on too much responsibility is by answering the simple question: If you had to take an unexpected week off work, would your initiatives and priorities advance in your absence? [4] A well-functioning team run by an effective leader should in theory be able to get by without that leader – for a period of time, at least. Whereas an organisation that orbits around the whims of a single figure is likely to stall, and fast. It’s why all good managers practice delegation.

Why delegate?

Delegation is something every business practices but not all do well. Just handing an employee some of the work does not count as delegation in any meaningful sense. Successful delegation involves genuinely trusting the employee and granting them autonomy. That can be a scary prospect for a leader used to having a controlling stake in all output. But there are ways to ensure that even without constant supervision, your team is working in a manner you approve.

The first is obviously to hire smart, capable workers to whom you feel comfortable delegating responsibility. Oftentimes leaders take on extra workplace burdens out of a lack of faith in their team. They think, “I’m not confident they have the ability to do the task,” and so instead choose to take it on themselves. But trust is paramount to any successful workplace. And to paraphrase Ernest Hemingway, the best way to know if you can trust an employee is to trust them – at least until they give you a reason not to. The best thing a leader can do is give their employees a chance and see what happens.

After all, a leader’s job is to get the best out of their employees. As Forbes writer Cynthia Knapek puts it, “Some people work to show you what their superpower is, but a good leader works to show you yours…you’ll never be a good delegator if you’re holding on to the belief that no one can do it as well as you can” [5].

Trusting your team – and shedding the arrogance of presuming you can do everything better yourself – is pivotal to good leadership. Refusing to cede control is the sign of an insecure leader, one who sees their role and status as proportional to their decision-making authority. They think that any act of delegation would lead to a dilution of their power.

This theory is backed up by a 2017 study on psychological power and the delegation of authority by Haselhuhn, Wong and Ormiston. They ultimately found that, “individuals who feel powerful are more willing to share their decision making authority with others. In contrast, individuals who feel relatively powerless are more likely to consolidate decision making authority and maintain primary control” [6]. Delegation is a sign of strength, not weakness. Consolidation of all authority is the remit of the insecure.

Another thing leaders can do to help ensure their team is working autonomously but towards a clear end goal is to have a solid set of principles in place. These principles shouldn’t just highlight the leader’s values and goals but make clear the approach they want to use to achieve them. Shift Thinking founder and CEO Mark Bonchek calls such a set of principles a company’s “doctrine”. Bonchek argues that, “without doctrine, it’s impossible for managers to let go without losing control. Instead, leaders must rely on active oversight and supervision. The opportunity is to replace processes that control behavior with principles that empower decision-making” [7].

Having a guiding set of principles in place lets you delegate responsibility more freely because you know that even with limitless autonomy, your employees are aware of the parameters they should be working within – it keeps them drawing within the lines.

Evidently, a pivotal part of leadership is and always will be people management. But if a leader has already clearly defined their principles, they’ll find they need to manage their people much less. Some companies that advocate for principles-based management include Amazon, Wikipedia and Google. The proof is in the pudding.

Effective delegation

How delegation is handled contributes enormously to what kind of company one is running and what kind of leader one is. For example, consider two scenarios. In scenario one, a tired and over involved leader, seeing that they have taken on more than they can chew with a deadline fast approaching, tells one of their team that they no longer have time to do a report that they were meant to be writing and so thrusts it on the employee to hastily pick up the slack.

In scenario two, a leader identifies a member of their team who they want to write a report for them. They talk to the employee and tell them that they’ve noticed the employee’s precision in putting facts across concisely and engagingly and want them to put those skills to use in this latest report. They talk through what they want from the project and why this employee is the perfect person to achieve those goals. They make known that they are available for support should any be needed.

In both examples, the boss is asking their employee to write a report. But in one that work is something fobbed off on the employee, a chore the leader no longer wants to do. In the second example, the leader is identifying the skills of a member of their team, letting the employee know that these are the skills needed for the task at hand and thus giving the employee an idea of what’s needed from them as well as a confidence boost.

Sostrin suggests four strategies for successful delegation [8]. First, to start with reasoning. As in the example above, this includes telling someone not just what work they want done but why – and that means both why they are working towards a certain goal and why the employee is the person to do it.

Second, to inspire their commitment. This, again, is about communication. By relaying the task at hand, their role in it and why it’s important, they can understand the bigger picture, not just their specific part of it. They’re then more able to bring themselves to the project, rather than viewing it as simply a tick-box exercise they’re completing for their boss.

Third, to engage at the right level. Of course delegation doesn’t mean that a leader should hand work over to their employees and then never worry about it again. They should maintain sufficient engagement levels so that they can offer support and accept accountability, but do so without stifling their team. The right balance depends on the organisation, the project and the personnel involved, but Sostrin suggests that simply asking staff what level of supervision they want can be a good start.

Fourth, to practise saying “yes”, “no”, and “yes, if”. That means taking on demands that you think are best suited to you, saying “yes, if” to those that would be better off delegated to someone more suited to that specific task, and giving outright “no”s to those you don’t deem worthwhile.

For example, Keith Underwood, COO and CFO of The Guardian, said that he doesn’t delegate when “the decision involves a sophisticated view of the context the organisation is operating in, has profound implications on the business, and when stakeholders expect me to have complete ownership of the decision” [9].

Kelly Devine, president of Mastercard UK and Ireland, says, “The only time I really feel it’s hard to delegate is when the decision is in a highly pressurised, contentious, or consequential situation, and I simply don’t want someone on my team to be carrying that burden alone” [10].

On top of these four, it’s worth adding the benefits around communicating high-profile, critical company decisions to your team, whether that be layoffs, new investors, or whatever the case may be. Leaders should want their employees to feel part of the organisation. That means keeping them in the loop of not just what is happening but why. Transparency is highly valued and in turn valuable.

In summary

It can be all too easy for managers who rose through the corporate ranks to eschew delegation in favour of an auteur-esque approach – shaping a team in their distinct image, if not actively trying to do all the work themselves. But delegation not only makes life less tiring and stressful for the leader, who cannot possibly hope to cover everyone’s work alone, but it also results in a happier, more productive, and likely more capable workforce, one that feels trusted and free to experiment rather than constrained by fear of failure.

Good ideas come from anywhere. Good organisations are built on trust. Good leaders don’t smother their workers but empower them. And with each empowered collaborator, the likelihood of collective success grows.

More on Trust

Leadership in Focus: Foundations and the Path Forward

Unleashing Leadership Excellence with Dan Pontefract (podcast)

References

[1] https://marshallgoldsmith.com/book-page-what-got-you-here/

[2] https://hbr.org/2017/10/to-be-a-great-leader-you-have-to-learn-how-to-delegate-well

[4] https://hbr.org/2017/10/to-be-a-great-leader-you-have-to-learn-how-to-delegate-well

[6] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0191886916311527

[7] https://hbr.org/2016/06/how-leaders-can-let-go-without-losing-control

[8] https://hbr.org/2017/10/to-be-a-great-leader-you-have-to-learn-how-to-delegate-well

[9] https://hbr.org/2023/03/5-strategies-to-empower-employees-to-make-decisions

[10] https://hbr.org/2023/03/5-strategies-to-empower-employees-to-make-decisions

Introduction

The role of a CEO, once defined by strategy charts and bottom lines, is undergoing a sea change. With constant technological advances, changing business complexities, and societal expectations, CEOs are required to expand their expertise beyond traditional business acumen. Today, a truly great CEO needs to master the art of social skills, demonstrating a keen ability to interact, coordinate, and communicate across multiple dimensions.

As the business landscape continues to grow more complex, the ability to navigate this intricacy has become a defining factor in effective leadership. This holds true for large, publicly-listed multinational corporations and medium to large companies operating in a rapidly evolving marketplace. As a result, leaders must possess the skills and acumen to navigate this complex landscape, make informed decisions, and steer their organisations toward success.

Social Skills

Top executives in these firms are expected to harness their social skills to coordinate diverse and specialised knowledge, solve organisational problems, and facilitate effective internal communication. Further, the interconnected web of critical relationships with external constituencies demands leaders to demonstrate adept communication skills and empathy.

The proliferation of information-processing technologies has also played a crucial role in defining a CEO’s success. As businesses increasingly automate routine tasks, leadership must offer a human touch—judgment, creativity, and perception—that can’t be replicated by technology. In technologically-intensive firms, CEOs need to align a heterogeneous workforce, manage unexpected events, and negotiate decision-making conflicts—tasks best accomplished with robust social skills.

Equally, with most companies relying on similar technological platforms, CEOs need to distinguish themselves through superior management of the people who utilise these tools. As tasks are delegated to technology, leaders with superior social skills will find themselves in high demand, commanding a premium in the labour market.

Transparency

The rise of social media and networking technologies has also transformed the role of CEOs. Moving away from the era of anonymity, CEOs are now expected to be public figures interacting transparently and personally with an increasingly broad range of stakeholders. With real-time platforms capturing and publicising every action, CEOs need to be adept at spontaneous communication and anticipate the ripple effects of their decisions.

Diversity & inclusion

In the contemporary world, great CEOs also need to navigate issues of diversity and inclusion. This calls for a theory of mind—a keen understanding of the mental states of others—enabling CEOs to resonate with diverse employee groups, represent their interests effectively, and create an environment where diverse talent can thrive. (See our article on the Chief Coaching Officer for an alternative solution to this issue)

Hiring strategies

Given this backdrop, it is essential for organisations to refocus their hiring and leadership development strategies. Instead of relying on traditional methods of leadership cultivation, companies need to build and evaluate social skills among potential leaders systematically.

Current practices, such as rotating through various departments, geographical postings, or executive development programs, aren’t enough. Firms need to design a comprehensive approach to building social skills, even prioritising them over technical skills. High-potential leaders should be placed in roles that require extensive interaction with varied employee populations and external constituencies, and their performance should be closely monitored.

Assessing social skills calls for innovative methods beyond the traditional criteria of work history, technical qualifications, and career trajectory. New tools are needed to provide an objective basis for evaluating and comparing people’s abilities in this domain. While some progress is being made with the use of AI and custom tools for lower-level job seekers, there is a need for further innovation in top-level searches.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the role of the CEO is more multifaceted than ever. The modern world demands executives to possess exceptional social skills, including effective communication, empathetic interaction, and proactive inclusion. Companies need to recognise this change and adapt their leadership development programs accordingly to cultivate CEOs who can effectively lead in the 21st century.

In order to thrive, workplaces need to build cohesive teams that are intrinsically motivated. In this insight piece we address ways of approaching, obtaining, optimising and sustaining performance.

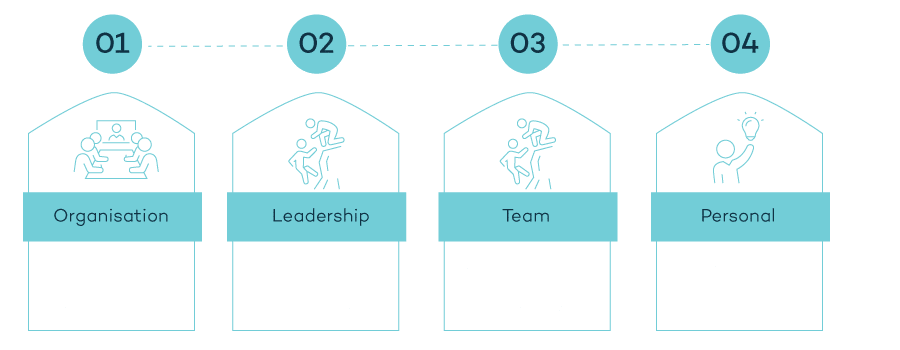

Every working environment is made up of four core layers:

Organisation

Leadership

Team

Personal

Within those layers exist both complementary and competing factors that can contribute to organisational growth. Some of these factors are in our control and can be strengthened directly, such as maintaining an active, healthy team and prioritising people development. Others are outside our scope, such as employee disengagement born of a change in personal priorities.

Linking each layer is a daily demand. Organisational design, positive leadership intent, a disciplined feedback loop and dedicated culture of growth must work in tandem. Improving and aligning each layer is pivotal.

- Every organisation needs to set out their strategic vision. Typically this outlines who the organisation is, what they stand for, their strengths, recent and notable successes, people development programmes and how to capitalise on future market opportunities.

Get right: Generate trust with a clear understanding of the journey ahead

Research shows that when it comes to maximising performance, trust is pivotal. An abundance of academic and anecdotal evidence points to trust’s long-term strategic value. Benefits include increased collaboration, vulnerability, communication and idea generation.

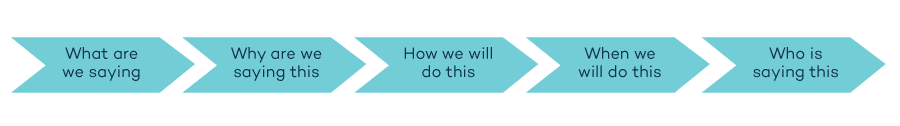

Communicating a coherent strategic vision requires a thoughtful engagement plan. Some important points include:

- An organisation’s strategy should flow downward and outward. For a strategy to successfully capitalise on opportunities, the leadership team needs to be aligned.

Get right: Leaders and leadership teams need to work on themselves first

Leadership teams are too often misaligned, leading to a lack of conviction in critical areas such as providing direction, communication (verbal and non-verbal) and role modelling positive behaviours. Obtaining a high standard of performance relies on resolute leadership alignment.

- A coherent strategic vision and aligned leadership group is a positive start. However, if mishandled, competing projects, team dynamics and internal politics can quickly hamper an organisation’s growth.

Get right: Ensure your teams provide consistent space for professionals to grow

Teams can better optimise their potential through an embedded performance professional (internal or external). Their fundamental role is to work with a team to provide objective feedback and help cultivate or better maintain high performance behaviours, all while keeping an eye on the wider professional context and the organisation’s long-term aims.

- Everyone has the potential to be a high performer. The necessary skills can be practised and honed. Curiosity to learn, a strong work ethic and leadership skills (such as a commitment to bettering others as well as oneself) are all indications of an individual primed for long-term sustainable performance.

Get right: Provide your people with the support to truly grow

Many traditional ‘off the shelf’ options are available for employees. Research suggests that organisations should actively focus on bespoke people development areas such as performance coaching. Shifting from a learning and development platform to a learning development experience is paramount to sustainable performance.

Interested in a further conversation about personal, team or leadership performance?

The persistent pulse of inquiry in history

Throughout history, our innate curiosity has been the heartbeat of progress, driving us from basic questions about nature, like “Why does it rain?” to profound existential inquiries, such as “Do we have free will?”. In today’s fast-paced world, the art of asking questions feels somewhat overshadowed by the avalanche of information available. Yet, recognising what we don’t know often serves as the true essence of wisdom.

One lasting method of exploring knowledge through questioning is the Socratic method, a tool from ancient Greece that aids critical thinking, helps unearth solutions, and fosters informed decisions. Its endurance for over 2,500 years stands as a testament to its potency. Plato, a student of Socrates, immortalised his teachings through dialogues or discourses. In these, he delved deep into the nature of justice in the “Republic”, examining the fabric of ideal societies and the character of the just individual.

Questions have not only transformed philosophy but also propelled innovations in various fields. Take, for instance, Alexander Graham Bell, whose inquiries led to the invention of the telephone or the challenges to traditional beliefs during the Renaissance that led to breakthroughs in art, science, and philosophy. With their profound questions about existence and knowledge, the likes of Kant and Descartes have shaped the philosophical narratives we discuss today.

Critical questioning has upended accepted norms in the scientific realm, leading to paradigm shifts. For example, Galileo’s scepticism of the geocentric model paved the way for ground-breaking discoveries by figures such as Aristarchus, Pythagoras, Copernicus, Newton, and Einstein. At its core, every scientific revolution was birthed from a fundamental question.

On the educational front, the importance of questioning is backed by modern research. Historically, educators have utilised questions to evaluate knowledge, enhance understanding, and cultivate critical thinking. Rather than simply prompting students to recall facts, effective questions stimulate deeper contemplation, urging students to analyse and evaluate concepts. This enriches classroom experiences and deepens understanding in experiential learning settings.

By embracing this age-old method and recognising the power of inquiry, we can better navigate the complexities of our contemporary world.

Questions through the ages: an enduring pursuit of truth

Throughout the annals of time, the act of questioning has permeated our shared human experience. While ancient civilisations like the Greeks laid intellectual foundations with their spirited debates and dialogues, their inquiries’ sheer depth and diversity stood out. These questions spanned from the cosmos’ intricate designs to the inner workings of the human soul.

Historical literature consistently echoed this thirst for understanding, whether in the East or West. It wasn’t just about obtaining answers; it celebrated the journey of arriving at them. The process, probing, introspection, and subsequent revelations hold a revered spot in our collective memory. The reverence with which we’ve held questions, as seen through the words of philosophers, poets, and thinkers, showcases the ceaseless human spirit in its quest for knowledge.

In today’s interconnected world, the legacy of these inquiries remains ever-pertinent. We live in an era of information, a double-edged sword presenting knowledge and misinformation. As we grapple with this deluge, the skills of discernment and critical inquiry, inherited from our ancestors, are invaluable. It’s no longer just about seeking answers but about discerning the truths among many voices.

With the current rise in misinformation and fake news, a sharpened sense of questioning becomes our compass, guiding us through the mazes of contemporary challenges. By honouring the traditions of the past and adapting them to our present, we continue our timeless pursuit of truth, ensuring that the pulse of inquiry beats strongly within us.

Understanding the Socratic Method

Having recognised the age-old reverence for inquiry, it becomes imperative to explore one of its most pivotal techniques: the Socratic method. Socrates, widely regarded as a paragon of wisdom, believed that life’s true essence lies in perpetual self-examination and introspection. His approach was unique in its time, as he dared to challenge societal norms and assumptions. When proclaimed the wisest man in Greece, he responded not with complacency but with probing inquiry.

The Socratic method transcends a mere question-answer paradigm. Instead, it becomes a catalyst, prompting deep reflection. This dialectical technique fosters enlightenment, not by spoon-feeding answers but by kindling the flames of critical thinking and understanding. The beauty of this method rests not solely in the answers it might yield, but in the journey of introspection and dialogue it necessitates.

Beyond philosophical discourses, this method resonates powerfully in contemporary educational spheres. It underscores that genuine knowledge transcends rote memorisation, emphasising comprehension and enlightenment. This reverence for knowledge stresses the imperative of recognising our limitations fostering an ethos where learning is ceaseless and dynamic.

In our information-saturated age, the Socratic method’s principles are not just philosophical musings but indispensable. According to Statistica, only about 26% of Americans feel adept at discerning fake news, while a concerning 90% inadvertently propagate misinformation. Herein lies the true power of the Socratic approach. It teaches us discernment, evaluation, and the courage to seek clarity continuously. By integrating this method into our lives, we are better equipped to navigate our intricate world, fostering lives marked by clarity, purpose, and profound understanding.

Why the question often surpasses the answer

Having delved into the rich tapestry of historical inquiry and the transformative power of the Socratic method, one may wonder: Why such an emphasis on the question rather than the answer?

We are often trained to seek definite conclusions throughout our educational journey and societal conditioning. Yet, as Socrates demonstrated through his dialogues, there’s profound wisdom in embracing the exploration inherent in questioning. His discussions rarely aimed for definitive answers, suggesting that the reflective process, rather than the conclusion, held deeper significance.

Imagine a complex puzzle. While the completed picture might offer satisfaction, aligning each piece, understanding its intricacies, and appreciating its nuances truly enriches the experience. Similarly, questions, even those without clear-cut resolutions, can expand our horizons, provoke self-assessment, and challenge our preconceived notions. This process broadens our perspectives and fosters a more holistic understanding of our surroundings.

By valuing the act of questioning, we equip ourselves with the tools to navigate ambiguity, confront our limitations, and engage with the world more thoughtfully and profoundly.

The Socratic Method in contemporary frameworks

Socratic questioning involves a disciplined and thoughtful dialogue between two or more people, and its methodologies, rooted in ancient philosophy, remain instrumental in today’s diverse contexts. In the realm of academia, especially within higher education, this collaborative form of questioning is a cornerstone. Educators don’t merely transfer information; they challenge students with introspective questions, compelling them to reflect, engage, and critically evaluate the content presented.

Beyond the classroom, the applicability of the Socratic method stretches wide. Business environments, such as boardrooms and innovation brainstorming sessions, harness the power of Socratic dialogue, pushing participants to confront and rethink assumptions. Professionals employ this method in therapeutic and counselling to guide clients in introspective exploration, encouraging clarity and self-awareness.

Through its emphasis on continuous dialogue, deep reflection, and the mutual pursuit of understanding, this age-old method remains a beacon, guiding us as we navigate the ever-evolving complexities of our modern world.

Conclusion: the timeless art of inquiry

From the cobbled streets of ancient Athens to contemporary classrooms, boardrooms, and counselling sessions, the enduring legacy of the Socratic method attests to the potent force of inquiry. By valuing the exploratory process as much as, if not more than, the final insight, we pave a path towards richer understanding, intellectual evolution, and the limitless possibilities of human achievement.

In today’s deluge of data and information, the allure of swift answers is undeniable. Yet, Socrates’ practice reminds us of the transformative power held in the act of questioning. Adopting such a mindset, as this iconic philosopher once did, extends an open invitation to a life punctuated by curiosity, wonder, and unending discovery.

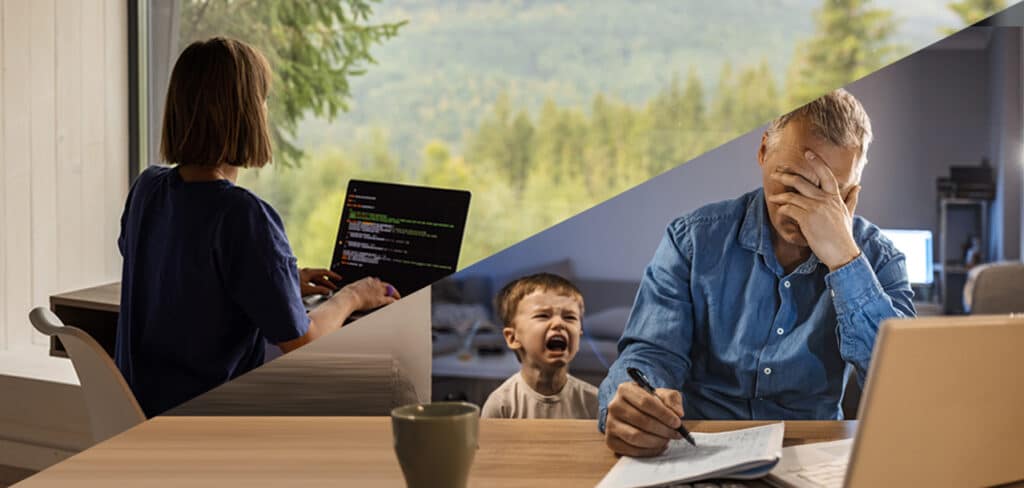

Depending on who you listen to working from home is either proof of a declining work ethic – evidence of and contributor to a global malaise that is hampering productivity, decimating work culture and amplifying isolation and laziness – or it’s a much-needed break from overzealous corporate control, finally giving workers the autonomy to do their jobs when, where and how they want to, with some added benefits to well-being, job satisfaction and quality of work baked in.

Three years on from the pandemic that made WFH models ubiquitous, the practice’s status is oddly divisive. CEOs malign it. Workers love it. Like most statements around WFH, that analysis is over simplistic. So what’s the actual truth: is WFH good, bad or somewhere in between?

The numbers

Before the pandemic Americans spent 5% of their working time at home. By spring 2020 the figure was 60% [1]. Over the following year, it declined to 35% and is currently stabilised at just over 25% [2]. A 2022 McKinsey survey found that 58% of employed respondents have the option to work from home for all or part of the week [3].

In the UK, according to data released by the Office for National Statistics in February, between September 2022 and January 2023, 16% of the workforce still worked solely from home, while 28% were hybrid workers who split their time between home and the office [4]. Meanwhile, back in 1981, only 1.5% of those in employment reported working mainly from home [5].

The trend is clear. Over the latter part of the 20th century and earliest part of the 21st, homeworking increased – not surprising given the advancements to technology over this period – but the increase wasn’t drastic. With Covid, it surged, necessarily, and proved itself functional and convenient enough that there was limited appetite to put it back in the box once the worst of the crisis was over.

The sceptics

Working from home “does not work for younger people, it doesn’t work for those who want to hustle, it doesn’t work in terms of spontaneous idea generation” and “it doesn’t work for culture.” That’s according to JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon [6]. People who work from home are “phoning it in” according to Elon Musk [7]. In-person engineers “get more done,” says Mark Zuckerberg, and “nothing can replace the ability to connect, observe, and create with peers that comes from being physically together,” says Disney CEO Bob Iger [8].

Meanwhile, 85% of employees who were working from home in 2021 said they wanted a hybrid approach of both home and office working in future [9]. It seems there’s a clash, then, between the wants of workers and the wants of their employers.

Brian Elliott, who previously led Slack’s Future Forum research consortium and now advises executive teams on flexible work arrangements, puts the disdain for WFH from major CEOs down to “executive nostalgia” [10].

Whatever the cause, and whether merited or not, feelings are strong – on both sides. Jonathan Levav, a Stanford Graduate School of Business professor who co-authored a widely cited paper finding that videoconferencing hampers idea generation, received furious responses from advocates of remote-work. “It’s become a religious belief rather than a thoughtful discussion,” he says [11].

In polarised times, it seems every issue becomes black or white and we must each choose a side to buy into dogmatically. Given the divide seems to exist between those at the upper end of the corporate ladder and those below, it’s especially easy for the WFH debate to fall into a form of tribal class warfare.

Part of the issue is that each side can point to studies showing the evident benefits of their point of view and the evident issues with their opponents. It’s the echo-chamber effect. Some studies show working from home to be more productive. Others show it to be less. Each tribe naturally gravitates to the evidence that best suits their argument. Nuance lies dead on the roadside.

Does WFH benefit productivity?

The jury is still out.

An Owl Labs report on the state of remote work in 2021 found that of those working from home during 2021, 90% of respondents said they were at least at the same productivity level working from home compared to the office and 55% said they worked more hours remotely than they did at the office [12].

On the other end of the spectrum, a paper from Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom, which reviewed existing studies on the topic, found that fully remote workforces on average had a reduced productivity of around 10% [13].

Harvard Business School professor Raj Choudhury, looking into government patent officers who could work from anywhere but gathered in-person several times a year, championed a hybrid approach. He found that teams who worked together between 25% and 40% of the time had the most novel work output – better results than those who spent less or more time in the office. Though he said that the in-person gatherings didn’t have to be once a week. Even just a few days each month saw a positive effect [14].

It’s not just about productivity though. Working from home can have a negative impact on career prospects if bosses maintain an executive nostalgia for the old ways of working. Studies show that proximity bias – the idea that being physically near your colleagues is an advantage – persists. A survey of 800 supervisors by the Society for Human Resource Management in 2021 found that 42% percent said that when assigning tasks, they sometimes forget about remote workers [15].

Similarly, a 2010 study by UC Davis professor Kimberly Elsbach found that when people are seen in the office, even when nothing is known about the quality of their work, they are perceived as more reliable and dependable – and if they are seen off-hours, more committed and dedicated [16].

Other considerations

It’s worth noting other factors outside of productivity that can contribute to the bottom line. As Bloom states, only focusing on productivity is “like saying I’ll never buy a Toyota because a Ferrari will go faster. Well, yes, but it’s a third the price. Fully remote work may be 10% less productive, but if it’s 15% cheaper, it’s actually a very profitable thing to do” [17].