Introduction

In the dynamic core of Silicon Valley, a start-up bursting with ambition and innovation faces an unexpected global challenge: a pandemic that reshapes economies and alters consumer behaviours overnight. This scenario epitomises the modern business landscape’s volatile and unpredictable nature. Here, traditional strategies rigorously test their mettle against the capricious forces of a world defined by its volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity – the VUCA world. This term, originating in the military and now deeply resonant in business discourse, frames our exploration of the 21st-century business environment’s challenges and opportunities.

Chapter 1: Dissecting the VUCA landscape

In the fast-paced, high-stakes world of contemporary business, understanding VUCA – Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity – is crucial for any organisation aspiring to survive and thrive. This section delves into these elements, weaving together real-world examples and strategic insights.

Volatility: Riding the economic tsunamis

Volatility is the chameleon of the business world, characterised by rapid, unpredictable changes. With its extreme price fluctuations, the cryptocurrency market is a stark example. Companies like Coinbase have flourished amidst this volatility by creating resilient, user-friendly platforms and diversifying their services, converting volatility from a formidable threat into a lucrative opportunity.

Uncertainty: Charting unknown waters

Where predictability dwindles, uncertainty thrives. Netflix’s bold transition in the mid-2000s from DVD rentals to online streaming is a testament to this. This leap into uncharted territory, powered by forward-thinking and a flexible business model, propelled Netflix to survive and revolutionise the entertainment industry.

Complexity: The intricate web of modern business

Business complexity arises from the dense interplay of numerous factors and variables. The global supply chain, a complex web involving suppliers, manufacturers, and distributors across continents, exemplifies this. Apple Inc.’s strategic management of its supply chain is a masterclass in navigating complexity, turning a potential logistical nightmare into a critical competitive edge.

Ambiguity: Navigating the mists of uncertainty

Ambiguity manifests in scenarios where information is limited, and the path forward is hazy. Google’s venture into autonomous vehicles is a prime example. Google embarks on this journey amidst nascent legal frameworks and uncertain public acceptance, pioneering a field where the rules are still being written.

In these cases, the companies involved have not just confronted their respective VUCA challenges; they have embraced and exploited them, transforming potential vulnerabilities into strengths. As a multifaceted concept, VUCA is integral in navigating challenges, ensuring sustained success, and fostering perseverance in turbulent times. This section has demonstrated that, despite their daunting nature, these elements can serve as powerful catalysts for developing innovative strategies and emerging ground-breaking leadership.

Chapter 2: Strategic responses to VUCA

In a world where the only constant is change, engaging in traditional strategic planning often resembles the challenge of trying to build a bridge during an earthquake. Elaborate five-year plans and detailed business models presuppose a level of stability that the VUCA world often mocks. These tools are like navigating a labyrinth that reshapes itself with every step. The real question isn’t the accuracy of the compass but whether a compass is the right tool in this ever-changing maze.

Enter agile methodologies, a philosophy nurtured in the trenches of software development but increasingly relevant across the broader business landscape. Agile transcends a mere collection of practices; it embodies a mindset that embraces change as an inevitable, integral part of the journey. It fosters adaptability, rapid feedback loops, and iterative development. In VUCA conditions, where the path ahead is often veiled in fog, agile strategies allow businesses to move forward in measured, confident steps, continuously inspecting and adapting their approach.

Consider a technology start-up navigating the whirlwind of market changes. Rather than a fixed product launch plan, they adopt a ‘release early, release often’ philosophy. Their product evolves through constant iteration, incorporating user feedback, responding to emerging trends, and pivoting when necessary. By choosing responsiveness over rigidity, the company ensures its product becomes more resilient and closely aligned with the market’s pulse.

Leadership in a VUCA world also takes on a different hue. The most effective leaders are those who find comfort in discomfort. They stand firm on the shifting sands of uncertainty, making decisions not by predicting the future but by preparing to meet it in various forms. These leaders often exhibit a high tolerance for ambiguity, a penchant for calculated risk-taking, and a knack for strategic foresight. They are adept at navigating the currents of volatility and discerning the signal from the noise in a complex world. Consider the CEO of a global logistics company that decentralises decision-making to empower regional managers amidst unpredictable international trade tensions. This leader understands that in a VUCA world, those closest to the action often have the best perspective for making swift, informed decisions.

Effectively navigating VUCA demands a blend of agile practices and a leadership style that relinquishes the illusion of control. It’s about crafting a strategy that’s less a rigid plan and more a flexible guide for dynamic decision-making – a strategy that points to true north but allows for various paths to reach it. Organisations that thrive use VUCA not as an excuse for paralysis but as a springboard for innovation, resilience, and transformation.

Chapter 3: Turning VUCA into opportunity

A hidden treasure lies in the swirling chaos of the VUCA world – the promise of innovation and a bastion of competitive advantage. Companies that recognise this don’t just aim to withstand the turmoil; they strive to harness it, grow from it, and emerge as leaders because of it.

In the VUCA world, the concept of antifragility comes to the forefront. This refers to systems that improve when exposed to shocks and stressors, turning potential disruptions into catalysts for growth. By embracing the upheaval of disruption, these organisations transform challenges into stepping stones for success.

Case Studies: VUCA champions

Amazon and Complexity: Amazon’s venture into cloud computing with AWS, initially seen as a departure from its retail roots, embraced the uncertainty of technological needs and propelled the company to a leadership position in cloud computing. AWS’s success clearly demonstrates how engaging with complexity can uncover new business frontiers.

Tesla and Volatility: Under Elon Musk’s leadership, Tesla has excelled by navigating the waves of volatility. The company’s unwavering commitment to innovation – from advanced battery technology to autonomous driving – has seen it shape and adapt to the evolving automotive sector. Tesla’s journey is a prime example of how volatility can fuel industry leadership.

Zoom and Ambiguity: Zoom’s rise during the pandemic illustrates triumph over ambiguity. As the world pivoted to remote interactions, Zoom swiftly adapted its platform to meet burgeoning demand across various sectors, becoming a staple in virtual communication.

These narratives show how embracing the inherent aspects of the VUCA environment can be a powerful driver for growth and innovation. Amazon’s strategic risk in a new domain, Tesla’s utilisation of market volatility for progressive innovation, and Zoom’s agile response to a global shift are all testament to the potential of antifragile approaches in business.

Chapter 4: Preparing for a VUCA future

As businesses sail the uncharted waters of a VUCA world, the challenge extends beyond mere survival tactics. It calls for cultivating capacities and competencies that transform volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity into instruments of strategic empowerment.

Cultivating a resilient and agile culture

They are thriving amid flux demands that organisations champion agility and resilience. To succeed in the VUCA world, companies must develop a skilled, adaptable, creative, and proficient workforce in critical thinking. It’s crucial to cultivate an environment that values continuous learning, one in which employees are consistently encouraged to keep up-to-date with industry trends and technological advancements.” Building a culture of constant learning, where employees are encouraged to stay abreast of industry trends and technological advances, is essential. Such a learning environment is strengthened by fostering collaboration and ensuring open communication, empowering teams to navigate complex and ambiguous scenarios with collective wisdom.

Harnessing the might of technology and analytics

In the crucible of VUCA, data is the alchemist’s stone, turning uncertainty into clarity. Leveraging technology and data analytics is crucial for informed decision-making. Advanced analytics, powered by AI and machine learning, dissect vast datasets to unveil trends and patterns, equipping businesses to anticipate market shifts and understand customer behaviour nuances.

Moreover, investing in robust digital infrastructure drives operational efficiency and ensures resilience. Tools that enable remote collaboration and flexibility are indispensable, fortifying businesses against unforeseen disruptions.

Strategic foresight through scenario planning

Scenario planning is a strategic foresight method, illuminating paths through the VUCA fog. Organisations can develop flexible strategies to adapt to various potential futures by envisioning different possible futures. This proactive approach minimises response lag, allowing businesses to transition smoothly, akin to a well-rehearsed ballet rather than a puppet’s reactive jerks.

Embracing the VUCA horizon

Looking ahead, it’s vital for leaders to actively engage with the VUCA elements, not just recognise them. Stepping beyond the comfort of predictability, they must view the dynamic VUCA elements as harbingers of opportunity. An ethos of innovation should permeate the organisation, where calculated risk-taking is the norm and change is the catalyst for growth.

Conclusion: Charting a course through VUCA waters

In the unfolding narrative of the 21st-century marketplace, the VUCA world emerges not as a transient challenge but as the sea upon which businesses must navigate. From innovative Silicon Valley start-ups to established global conglomerates, the relentless tempest of Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity is a constant presence. Yet, within this tempest, the most significant opportunities for innovation, strategic success, and transformative leadership are hidden.

Businesses thriving in this environment do not just react to change; they anticipate, adapt, and harness it as a driving force. The stories of companies like Coinbase, Netflix, Apple, Google, Amazon, Tesla, and Zoom demonstrate that navigating VUCA conditions can turn potential vulnerabilities into unmatched strengths. These organisations show us that the heart of chaos is not just a challenge to be overcome but a landscape rich with opportunities for growth and leadership.

As we move into an increasingly complex and unpredictable future, the key takeaway for businesses is the importance of cultivating an agile and resilient mindset. Embracing change as a constant, leveraging technology and data for strategic insights, and fostering a culture where innovation and adaptability are prioritised are essential strategies for thriving in a VUCA world. Scenario planning and strategic foresight become invaluable tools, enabling organisations to envision multiple futures and prepare for them with flexibility and agility.

Leadership in a VUCA world is less about commanding with absolute certainty and more about guiding with adaptive clarity. It calls for a new breed of leaders – those who are comfortable navigating uncharted waters, can turn uncertainty into a strategic advantage, and inspire their teams to embrace the VUCA elements not as threats but as opportunities for innovation and growth.

In conclusion, the journey through the VUCA landscape offers valuable lessons. It teaches us that the future belongs to those who are ready to face this dynamic world’s inherent challenges. Moreover, it’s not just about readiness; it’s about being equipped to harness the VUCA world’s power. This approach paves the way for a voyage marked by discovery, innovation, and triumphant success. The VUCA world is not a barrier to victory but a multifaceted environment where the agile, the resilient, and the visionary can thrive. As we chart our course through these tumultuous waters, let us embrace the winds of change as they propel us towards new horizons of opportunity and achievement.

More on Adaptability

Leadership in Focus: Foundations and the Path Forward article by Shay Dalton

From Oracles to Algorithms: A Golden Age of Prediction article by Shay Dalton

Introduction

Cohesion is pivotal to the success of any effective organisation. It is the means by which teams work in unison towards a shared objective, each member working closely with and bouncing off their colleagues to contribute to a larger goal.

Covid-19 impacted many aspects of work life, cohesion included. In some ways, by fast-tracking the shift to a hybrid working model, the pandemic enhanced our ability to engage with others easily, regardless of location, allowing us to leverage global insights that were previously unreachable. However, it also diminished our ability to build and develop the in-person connections that are so vital to forming an effective, synchronised team.

Type ‘team cohesion’ into Google and you’ll get over 17 million search results, with everything from courses, books, talks, techniques and opinions freely available.

But while heaps of information on the subject are easily accessible, specific context and sequencing are required if we are to turn that mass of information into actualised, meaningful team growth. Here, we outline the five essential elements that make for better team cohesion.

1. A unifying vision

For an organisation to thrive, the company and its employees must be aligned. Recognising that each employee brings their own unique set of values, motivations, fears, expectations, and growth potential is key. The best organisations know how to integrate these individual values within a wider organisational purpose.

2. Intentional leadership

Leaders wield immense influence in setting the right tone amongst a team, one that can be easily bought into and upheld whether they’re in the room or not. When that tone is right, mood and productivity go up. When it falters, productivity takes a hit. Leaders must embody their values and make them resonate amongst their staff to get everyone moving as a unit toward a single shared vision.

3. Management skills

Without fail, the best teams and organisations are led by figures who possess a distinct ability to empower others. Great managers recognise the untapped potential of those around them and know how to draw it out. They foster autonomy in their staff, hold themselves accountable, offer candid feedback and are open to receiving it as well.

4. Team dynamics

There are, of course, many challenges when it comes to maintaining team dynamics. Leaders need to be on the lookout not just for what their staff are telling them, but for non-verbal cues too – body language, facial reactions etc. It’s not easy, especially as work environments become increasingly digitalised. Still, there are some steps leaders can take to ensure their work environment is functioning at its best, such as promoting:

- Cognitive diversity: Fostering an inclusive environment that encourages a diverse blend of thoughts, experiences, and backgrounds to freely converge and collectively question the status quo.

- Psychological safety: The degree to which one expresses oneself directly correlates to the level of psychological safety they feel. Building a level of trust (outward) and felt trust (inward) will allow employees to drop their guard and be themselves, resulting in their best work.

- Friction: True innovation and learning are the product of differences. It’s only in challenging ideas that we learn their strength. Be sure to promote a healthy amount of challenge within your team, though one that does not impinge on psychological safety.

5. Individual performance

A team is made up of individuals. As such, every individual’s attitude and performance will in turn impact team cohesion. Further developing two aspects of individual performance can go a long way.

- Mindset: Encourage individuals in your team to develop deliberate behaviours such as habit building. A routine habit improves short-term performance and creates a robust psychological framework from which to build sustainable long-term improvement.

- Presence: Encourage employees to focus on the present. It’s all too easy to get caught up in future aspirations and past successes or failures. Connecting to one’s present surroundings allows for all sorts of previously impossible benefits. As well as benefiting staff experience and productivity, it allows for an openness that often proves fertile for coming up with innovative ideas.

Conclusion

Team cohesion is a fundamental driver of sustained, long-term success. Cohesion is a product of gradual development; building strong relationships requires a shared understanding that can only evolve from an environment that fosters mutual trust among team members. Understanding a colleague – their motivations, their life experience – and offering tailored support requires an investment that extends far beyond routine check-ins or daily project collaborations.

As we delve deeper into the ‘Future of Work,’ teams are in the process of establishing new behavioural norms and practices. Investing in and cultivating team cohesion instils confidence in organisations and generates substantial long-term returns on investment.

More on Teamwork

The Power of Team Clusters: A People-Centric Approach to Innovation

On the evening of Tuesday November 21st an exclusive gathering of business leaders came together in the elegant surroundings of 25 Fitzwilliam Place for a Leadership Masterclass with Steering Point Leadership and Talent Development Director, Jonny Cooper and Minister Paschal Donohue.

Steering Point Founder and Partner Shay Dalton opened the evening welcoming the Minister and thanking sponsors, TowerView for supporting the event.

During the conversation Minister Donohue related to Jonny Cooper how he manages the responsibilities associated with being Minister for Public Expenditure and Reform in Ireland, President of the Eurogroup and representative for Dublin Central constituency. A consistent presence of mind, clarity of thought and an ability to navigate complexity with his team all play crucial parts in the balancing of his demanding daily routine.

Minister Donohue emphasised the importance of staying laser-focused on the task at hand, even when attention is diverted. He also shared his approach to balancing home life with political responsibilities and the value of maintaining interests outside of work.

Finally, the Minister stressed the significance of having a mentor or trusted advisor, someone to consult with when making big decisions or identifying potential blind spots in a constantly evolving world.

“A memorable and interactive night in the company of distinguished and successful leaders at our Steering Point Leadership Dinner series.” said Cooper “During his masterclass Minister Paschal Donohue was able to impart his depth of knowledge and experience in an intimate manner. From the positive feedback received so far it is evident that our clients and friends walked away with something very special.”

Attendees spoke highly of the evening with one guest, Colm Woods MD of CW8 Communications commenting “Even with the terrific room full of business leaders, the standout for everyone was undoubtedly the candid and wide-ranging conversation between Jonny and Minister Donohoe. Humility, affability, integrity, honesty, dedication – all the qualities that one should aspire to in leadership, evident for all to see on both sides of the chat. A conversation that will stay with me for some time.”

Gallery

For media inquiries or to request high resolution photography from the evening contact Steering Point Group Head of Marketing Gail Finegan, gfinegan@steeringpoint.ie.

Introduction

Sometimes, even the most passionate and dedicated individuals can experience a dip in motivation and passion for their work or career. If you find yourself in this situation, you’re not alone. The good news is that there are ways to rekindle your passion and reignite your drive to excel. In this post, we’ll explore some psychological theories of motivation and social psychology concepts that can provide practical advice for reigniting the spark in your professional life.

Self-Determination Theory

First, let’s delve into the psychological theories of motivation. One such theory is the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) by Deci and Ryan (1985), which focuses on the concepts of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. According to SDT, people are more likely to be motivated when they feel a sense of control over their actions, believe they can succeed, and feel connected to others. To apply this theory to your work life, consider seeking opportunities for autonomy, setting achievable goals, and fostering positive relationships with colleagues.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Another relevant psychological theory is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (1943), which posits that people are motivated by fulfilling their basic needs before moving on to higher-order needs, such as self-esteem and self-actualisation. To rekindle your passion, examine whether your basic needs are being met at work, such as having a safe environment, job security, and social connections. If not, address these areas first to create a solid foundation for reigniting your passion.

Social identity theory

Turning to social psychology, the concept of social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) suggests that individuals derive a sense of self-worth and belonging from their group memberships. In the context of work, identifying with your organisation or team can contribute to increased motivation and passion. To foster this sense of belonging, engage in team-building activities, share your organisation’s mission and values, and celebrate your team’s achievements.

Reigniting your passion

Now that we’ve explored some relevant theories let’s discuss practical tips for reigniting your passion at work:

- Reflect on your “why”: Revisit the reasons you initially chose your career or job, and remind yourself of what ignited your passion in the first place. This exercise can help you rediscover your purpose and motivation.

- Seek new challenges: Taking on new responsibilities or learning new skills can reignite your passion by pushing you out of your comfort zone and reigniting your curiosity.

- Connect with inspiring individuals: Surrounding yourself with passionate and motivated people can be contagious. Seek out colleagues, mentors, or role models who inspire and challenge you.

- Set SMART goals: Establish Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound goals that align with your values and interests, and celebrate your progress along the way.

- Practice self-care: Prioritise your mental and physical well-being by setting boundaries, managing stress, and engaging in activities that bring you joy.

- Cultivate gratitude: Regularly reflecting on your accomplishments and expressing gratitude for your job can help shift your focus from negative aspects to positive aspects of your work.

Conclusion

In conclusion, reigniting your passion for work or your career requires a combination of understanding the underlying psychological and social factors and implementing practical strategies. By drawing on the theories of motivation and social psychology, you can create a more fulfilling and passionate work life that drives you to excel.

More on Motivation

The Workplace Motivation Theory That Works

Organisational Psychology and Motivation

Emotional Intelligence and Engaging Others

References

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behaviour. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268.

Dweck, C. S. (2008). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House Digital, Inc.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370-396.

Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Riverhead Books.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realise your potential for lasting fulfilment. Free Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33-47). Brooks/Cole.

Vallerand, R. J., & Houlfort, N. (2003). Passion at work: Toward a new conceptualisation. In

S. W. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, & D. P. Skarlicki (Eds.), Emerging perspectives on values in organisations (pp. 175-204). Information Age Publishing.

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at one of the most commonly used motivation theories in the workplace and explore how self-determination can be balanced with autonomy and alignment to organisational strategy.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is a framework for understanding the factors that promote or undermine intrinsic motivation, which refers to doing something because it is inherently interesting or enjoyable rather than because of external rewards or pressure.

Self-Determination Theory

According to SDT, three basic psychological needs must be satisfied to foster intrinsic motivation: autonomy (having control over one’s own actions), competence (feeling capable and effective), and relatedness (feeling connected to others) (Ryan & Deci, 2020). When these needs are met, people are more likely to feel intrinsically motivated and engaged in their work.

In practice, employers can apply SDT principles by providing employees with opportunities to make choices, express creativity, and take on meaningful projects that align with their interests and values (autonomy); by offering training and support to help employees develop their skills and expertise (competence); and by fostering a sense of community and teamwork, and providing regular feedback and recognition (relatedness) (Deci et al., 2017).

Autonomy vs alignment

While some may wonder how to balance autonomy and alignment to overall strategy, it’s important to understand that autonomy and alignment are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they can complement each other and enhance employee motivation, job satisfaction, and organisational performance.

To achieve this balance, employers can provide employees with a clear understanding of how their work contributes to the organisation’s overall strategy. When employees understand how their work fits into the big picture, they are more likely to feel a sense of purpose and alignment and can make informed choices about how to approach their work in a way that supports the overall goals of the organisation.

At the same time, employers can provide employees with a degree of autonomy in how they approach their work. This can be achieved by giving them the freedom to make decisions about how to carry out their tasks, providing opportunities for them to take on projects that align with their interests and skills, and empowering them to innovate and generate new ideas.

In practice

Here are some practical tips for balancing autonomy and alignment in the workplace:

- Clarify the overall strategy: Ensure that employees understand the organisation’s overall strategy and how their work contributes to it. This can be achieved through regular communication, setting clear goals and expectations, and providing context and feedback on how their work impacts the organisation.

- Provide autonomy within parameters: Provide employees with a degree of autonomy in how they approach their work while ensuring they understand their role’s parameters and expectations. This can be achieved through clearly defining job responsibilities and expectations and providing opportunities for employees to make decisions within their roles.

- Foster a culture of innovation: Encourage employees to generate new ideas and take calculated risks to support the organisation’s overall strategy. This can be achieved through providing resources and support for innovation, recognising and rewarding creative thinking, and creating a safe and supportive environment for employees to take risks.

- Empower employees to make choices: Provide employees with opportunities to make choices about their work, such as setting their own goals, determining their own work schedules, and selecting projects that align with their interests and skills. This can help to foster a sense of ownership and accountability for their work.

Summary

In summary, combining autonomy and alignment with overall strategy is essential for creating a motivated and engaged workforce. By providing employees with a clear understanding of the overall strategy and the autonomy to make decisions within their role, organisations can create a culture of innovation and creativity that supports both individual and organisational goals.

References

Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 19-43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Motivation is one of the key factors that drives employees to work towards achieving their goals in the workplace. In a competitive business environment, organisations constantly seek ways to motivate their employees to improve productivity and performance. Organisational psychologists play a critical role in designing and implementing motivational strategies that can drive employees to perform at their best. This article will discuss various types of motivation that an organisational psychologist may recommend in a workplace.

Motivation theories

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory: Maslow’s theory is one of the oldest and most well-known motivational theories. The theory proposes that humans have five basic needs: physiological, safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization. The theory suggests that these needs form a hierarchy, with the most basic needs at the bottom of the hierarchy and the most advanced needs at the top. The theory suggests that as lower-level needs are met, employees are motivated to move up the hierarchy to meet higher-level needs.

- Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory: Herzberg’s theory suggests that two types of factors affect motivation: hygiene factors and motivators. Hygiene factors are factors that do not lead to motivation, but their absence can lead to dissatisfaction. Examples of hygiene factors include salary, working conditions, and job security. On the other hand, motivators are factors that directly contribute to motivation. Examples of motivators include recognition, responsibility, and opportunities for growth and development.

- Self-Determination Theory: Self-determination theory proposes that people are naturally motivated to grow, develop, and achieve their goals. The theory suggests that individuals are motivated when they feel a sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Autonomy refers to the need to have control over one’s own life, competence refers to the need to feel capable and effective, and relatedness refers to the need to feel connected to others.

- Expectancy Theory: Expectancy theory suggests that motivation is driven by the belief that effort leads to performance, performance leads to rewards, and rewards are valuable to the individual. The theory suggests that individuals are motivated when they believe that their effort will lead to good performance and that good performance will lead to valuable rewards.

Application of motivational theories

These motivational theories can be applied in a variety of ways in the workplace. For example, organisations can apply Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory by ensuring that their employees have access to basic physiological and safety needs such as adequate rest and comfortable working conditions. They can also provide opportunities for growth and development to help employees achieve their self-actualization needs.

Herzberg’s Two-Factor theory can be applied by ensuring that hygiene factors such as job security and salary are in place while also providing opportunities for recognition and responsibility to serve as motivators.

Self-determination theory can be applied by allowing employees to have more autonomy in their work, providing opportunities for skill-building and development, and creating a supportive work environment that fosters positive relationships.

Expectancy theory can be applied by setting clear performance expectations, providing resources and support to help employees achieve those expectations, and offering valuable and meaningful rewards.

Examples

One example of a company that has successfully applied motivational theories in their workplace is Google. Google provides its employees with a supportive work environment, ample opportunities for growth and development, and a range of benefits such as free meals and on-site healthcare. The company also encourages autonomy by allowing its employees to work on projects that interest them, and recognises their achievements through its “Peer Bonus” program.

Another example is Zappos, an online shoe and clothing retailer. Zappos offers regular feedback, encourages autonomy and provides opportunities for growth and development by allowing its employees to take on new roles and responsibilities.

In the recent coverage after Queen Elizabeth’s passing, I heard someone who worked with her say that she had an independent mind and where appropriate would go against popular opinion or the general consensus. While one of the hallmarks of a democracy or a healthy organisation is the ability of free speech or for divergent opinions to be heard. But at other times thinking seems to converge and conform. To explain why we look back to one of the most influential social psychologists, Solomon Asch, who pioneered work in the area of conformity and group thinking.

Solomon Asch was a Polish American psychologist who pioneered social psychology through the study of Gestalt psychology. Among the topics he researched were how people form impressions of others and how prestige may affect judgements. Group pressure and conformity are two of Asch’s greatest contributions. In 2002, the Review of General Psychology ranked Asch as the 41st most cited psychologist of the 20th century.

Building on and critiquing the work of the prominent social psychologist Muzafer Sherif, Asch, developed his own research into the areas of group pressure experiments and demonstrated the influence of group pressure on opinions in his conformity experiments.

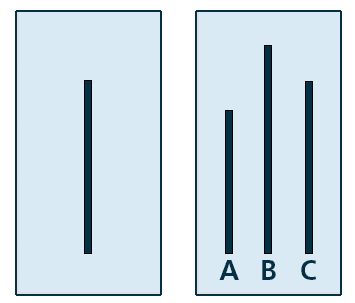

Asch came up with another conformity experiment but this time, he made sure that a task with an obvious, unambiguous answer was presented. In 1951, Asch presented the now regarded classic experiment in social psychology using a line judgment task.

Which of these three lines is the same length as the lonesome line on the left?

And yet in Asch’s conformity experiment conducted in the 1950s, 76 percent of people denied their own senses at least once, choosing either A or B.

The main purpose of this experiment was to understand how peer pressure could force people to conform, even when they were aware that the rest of the group was wrong. This included how people are likely to agree to a false answer just because most of the group has sided with the wrong answer. Asch indicated that in many settings, there is always a likelihood that many people doubt their opinions, where the “social process is polluted” (Asch, 1955) and therefore end up siding with a majority of the group either because they doubt being right or they fear being seen as different. This often happens in different contexts including situations where the answer is obvious, and that “any given idea or value can be “sold” or “unsold” without reference to its merits” (Asch, 1955). Asch’s research revealed the strength of social influence and continues to inspire social psychology scholars to this day.

Further conformity research and Asch’s legacy

Further research on conformity highlighted that the results in the Asch experiment, while significant to social psychology thinking, were to some extent “a child of their generation” and culture. Spencer and Perrin (1980) introduced similar research, introducing a more complex test.

A major difference between learners in the 1950’s and 1980’s is that the learners, in the1950’s, were more subjective and were more likely to join in with the larger population to belong and be viewed as a rising member.

Asch’s work has influenced how psychologists think about and research social influence in groups (Levine, 1999). His studies on independence and conformity are his most well-known and validated accomplishments. It is apparent from the Asch conformity experiment that people’s opinions are strongly influenced by the people around them. In fact, the Asch conformity experiment demonstrates how willing many people are to deny their own senses for the sake of conformity. The human race is naturally conformist, copying one another’s dress sense, ways of talking, and attitudes without hesitation.

Asch showed that people were willing to overlook reality and give an inaccurate answer to fit in with the rest of the group. Asch argued that “it brings into conflict two powerful forces by which we construct reality; our own subjective experience, and intersubjective agreement.” (Rock & Rock, 2014).

In addition, it can be seen from the wider Asch research and later research that effective group functioning relies on independence (Kampmeier & Simon, 2001; Graupensperger & Benson), and that independence and conformity are not just mirror images that may be explained by a single psychological process (Levine, 1999).

Types of conformity

Conformity is classified into two categories: public (compliance) and private (acceptance). Conformity is a movement toward a set of group norms, so compliance refers to behaviours that are overtly aligned with those norms, while acceptance refers to attitudes and perceptions that are covert. Compliance occurs, for instance, if an individual refuses to sign a petition advocating immigration, learns that a group advocates them, and then signs one. Alternatively, if a person secretly believed that immigration should be outlawed, learned that certain groups advocated immigration rights, and then changed his private opinion, he would show acceptance. The two most important forms of nonconformity are independence and anti-conformity. Individuals who are independent exhibit neither compliance nor acceptance after being subjected to the pressure of a group at first. When confronted with disagreement, a person stands firm. The opposite of conformity is anti-conformity, which occurs when a person initially disagrees with a group after which they move even further away from its position (at a public or private level). (Interestingly, anti-conformers are just as susceptible to group pressure as conformers, but they move away from the group to demonstrate their susceptibility.)

The role of motivation

A person conforms to group pressure to satisfy two important desires: the desire to perceive reality accurately and to be accepted by others. The reason people hold accurate beliefs about the world is because such beliefs usually lead to positive outcomes. Several beliefs about the world can be verified objectively; other beliefs cannot be verified objectively, and must be verified through social means, namely by comparison with those held by other people whose judgment one respects. One gains confidence in others if they agree with one’s beliefs; one loses confidence if they disagree. To eliminate disagreement, people conform to group norms.

Despite being similar and related concepts, conformity and groupthink have important differences. A groupthink process involves decision-making. In contrast, conformity refers to people changing their own behaviour to fit in with specific groups. We will focus on group think in a future post.

Overall, studies demonstrate that most people ‘tell the truth even when others do not’, Hodges and Geyer (2006). The Asch studies demonstrated that people may conform even when no evident pressure is applied, as well as how quickly they can shift when confronted with contradictory information.

More on Conformity

- “Groupthink occurs when people override their common sense desire to present alternatives, critique positions, or express unpopular opinions” (Read more)

References

Asch, S. E. (1955). Opinions and social pressure. Scientific American, 193(5), 31-35.

Graupensperger, S. A., Benson, A. J., & Evans, M. B. (2018). Everyone else is doing it: The association between social identity and susceptibility to peer influence in NCAA athletes. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 40(3), 117-127.

Hodges, B. H., & Geyer, A. L. (2006). A nonconformist account of the Asch experiments: Values, pragmatics, and moral dilemmas. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(1), 2-19.

Kampmeier, C., & Simon, B. (2001). Individuality and group formation: The role of independence and differentiation. Journal of personality and social psychology, 81(3), 448.

Levine, J. M. (1999). Solomon Asch’s legacy for group research. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(4), 358-364.

Perrin, S., & Spencer, C. (1980). The Asch effect-A child of its time. Bulletin of the British Psychological Society, 33(NOV), 405-406.

Rock, I., & Rock-DECEASED, I. (2014). The legacy of Solomon Asch: Essays in cognition and social psychology. Psychology Press