Introduction

The role of a CEO, once defined by strategy charts and bottom lines, is undergoing a sea change. With constant technological advances, changing business complexities, and societal expectations, CEOs are required to expand their expertise beyond traditional business acumen. Today, a truly great CEO needs to master the art of social skills, demonstrating a keen ability to interact, coordinate, and communicate across multiple dimensions.

As the business landscape continues to grow more complex, the ability to navigate this intricacy has become a defining factor in effective leadership. This holds true for large, publicly-listed multinational corporations and medium to large companies operating in a rapidly evolving marketplace. As a result, leaders must possess the skills and acumen to navigate this complex landscape, make informed decisions, and steer their organisations toward success.

Social Skills

Top executives in these firms are expected to harness their social skills to coordinate diverse and specialised knowledge, solve organisational problems, and facilitate effective internal communication. Further, the interconnected web of critical relationships with external constituencies demands leaders to demonstrate adept communication skills and empathy.

The proliferation of information-processing technologies has also played a crucial role in defining a CEO’s success. As businesses increasingly automate routine tasks, leadership must offer a human touch—judgment, creativity, and perception—that can’t be replicated by technology. In technologically-intensive firms, CEOs need to align a heterogeneous workforce, manage unexpected events, and negotiate decision-making conflicts—tasks best accomplished with robust social skills.

Equally, with most companies relying on similar technological platforms, CEOs need to distinguish themselves through superior management of the people who utilise these tools. As tasks are delegated to technology, leaders with superior social skills will find themselves in high demand, commanding a premium in the labour market.

Transparency

The rise of social media and networking technologies has also transformed the role of CEOs. Moving away from the era of anonymity, CEOs are now expected to be public figures interacting transparently and personally with an increasingly broad range of stakeholders. With real-time platforms capturing and publicising every action, CEOs need to be adept at spontaneous communication and anticipate the ripple effects of their decisions.

Diversity & inclusion

In the contemporary world, great CEOs also need to navigate issues of diversity and inclusion. This calls for a theory of mind—a keen understanding of the mental states of others—enabling CEOs to resonate with diverse employee groups, represent their interests effectively, and create an environment where diverse talent can thrive. (See our article on the Chief Coaching Officer for an alternative solution to this issue)

Hiring strategies

Given this backdrop, it is essential for organisations to refocus their hiring and leadership development strategies. Instead of relying on traditional methods of leadership cultivation, companies need to build and evaluate social skills among potential leaders systematically.

Current practices, such as rotating through various departments, geographical postings, or executive development programs, aren’t enough. Firms need to design a comprehensive approach to building social skills, even prioritising them over technical skills. High-potential leaders should be placed in roles that require extensive interaction with varied employee populations and external constituencies, and their performance should be closely monitored.

Assessing social skills calls for innovative methods beyond the traditional criteria of work history, technical qualifications, and career trajectory. New tools are needed to provide an objective basis for evaluating and comparing people’s abilities in this domain. While some progress is being made with the use of AI and custom tools for lower-level job seekers, there is a need for further innovation in top-level searches.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the role of the CEO is more multifaceted than ever. The modern world demands executives to possess exceptional social skills, including effective communication, empathetic interaction, and proactive inclusion. Companies need to recognise this change and adapt their leadership development programs accordingly to cultivate CEOs who can effectively lead in the 21st century.

In order to thrive, workplaces need to build cohesive teams that are intrinsically motivated. In this insight piece we address ways of approaching, obtaining, optimising and sustaining performance.

Every working environment is made up of four core layers:

Organisation

Leadership

Team

Personal

Within those layers exist both complementary and competing factors that can contribute to organisational growth. Some of these factors are in our control and can be strengthened directly, such as maintaining an active, healthy team and prioritising people development. Others are outside our scope, such as employee disengagement born of a change in personal priorities.

Linking each layer is a daily demand. Organisational design, positive leadership intent, a disciplined feedback loop and dedicated culture of growth must work in tandem. Improving and aligning each layer is pivotal.

- Every organisation needs to set out their strategic vision. Typically this outlines who the organisation is, what they stand for, their strengths, recent and notable successes, people development programmes and how to capitalise on future market opportunities.

Get right: Generate trust with a clear understanding of the journey ahead

Research shows that when it comes to maximising performance, trust is pivotal. An abundance of academic and anecdotal evidence points to trust’s long-term strategic value. Benefits include increased collaboration, vulnerability, communication and idea generation.

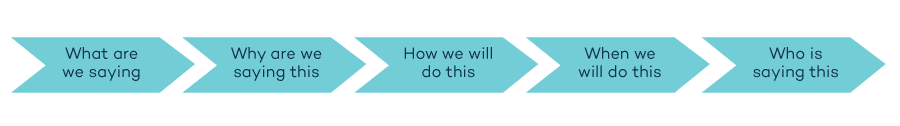

Communicating a coherent strategic vision requires a thoughtful engagement plan. Some important points include:

- An organisation’s strategy should flow downward and outward. For a strategy to successfully capitalise on opportunities, the leadership team needs to be aligned.

Get right: Leaders and leadership teams need to work on themselves first

Leadership teams are too often misaligned, leading to a lack of conviction in critical areas such as providing direction, communication (verbal and non-verbal) and role modelling positive behaviours. Obtaining a high standard of performance relies on resolute leadership alignment.

- A coherent strategic vision and aligned leadership group is a positive start. However, if mishandled, competing projects, team dynamics and internal politics can quickly hamper an organisation’s growth.

Get right: Ensure your teams provide consistent space for professionals to grow

Teams can better optimise their potential through an embedded performance professional (internal or external). Their fundamental role is to work with a team to provide objective feedback and help cultivate or better maintain high performance behaviours, all while keeping an eye on the wider professional context and the organisation’s long-term aims.

- Everyone has the potential to be a high performer. The necessary skills can be practised and honed. Curiosity to learn, a strong work ethic and leadership skills (such as a commitment to bettering others as well as oneself) are all indications of an individual primed for long-term sustainable performance.

Get right: Provide your people with the support to truly grow

Many traditional ‘off the shelf’ options are available for employees. Research suggests that organisations should actively focus on bespoke people development areas such as performance coaching. Shifting from a learning and development platform to a learning development experience is paramount to sustainable performance.

Interested in a further conversation about personal, team or leadership performance?

The persistent pulse of inquiry in history

Throughout history, our innate curiosity has been the heartbeat of progress, driving us from basic questions about nature, like “Why does it rain?” to profound existential inquiries, such as “Do we have free will?”. In today’s fast-paced world, the art of asking questions feels somewhat overshadowed by the avalanche of information available. Yet, recognising what we don’t know often serves as the true essence of wisdom.

One lasting method of exploring knowledge through questioning is the Socratic method, a tool from ancient Greece that aids critical thinking, helps unearth solutions, and fosters informed decisions. Its endurance for over 2,500 years stands as a testament to its potency. Plato, a student of Socrates, immortalised his teachings through dialogues or discourses. In these, he delved deep into the nature of justice in the “Republic”, examining the fabric of ideal societies and the character of the just individual.

Questions have not only transformed philosophy but also propelled innovations in various fields. Take, for instance, Alexander Graham Bell, whose inquiries led to the invention of the telephone or the challenges to traditional beliefs during the Renaissance that led to breakthroughs in art, science, and philosophy. With their profound questions about existence and knowledge, the likes of Kant and Descartes have shaped the philosophical narratives we discuss today.

Critical questioning has upended accepted norms in the scientific realm, leading to paradigm shifts. For example, Galileo’s scepticism of the geocentric model paved the way for ground-breaking discoveries by figures such as Aristarchus, Pythagoras, Copernicus, Newton, and Einstein. At its core, every scientific revolution was birthed from a fundamental question.

On the educational front, the importance of questioning is backed by modern research. Historically, educators have utilised questions to evaluate knowledge, enhance understanding, and cultivate critical thinking. Rather than simply prompting students to recall facts, effective questions stimulate deeper contemplation, urging students to analyse and evaluate concepts. This enriches classroom experiences and deepens understanding in experiential learning settings.

By embracing this age-old method and recognising the power of inquiry, we can better navigate the complexities of our contemporary world.

Questions through the ages: an enduring pursuit of truth

Throughout the annals of time, the act of questioning has permeated our shared human experience. While ancient civilisations like the Greeks laid intellectual foundations with their spirited debates and dialogues, their inquiries’ sheer depth and diversity stood out. These questions spanned from the cosmos’ intricate designs to the inner workings of the human soul.

Historical literature consistently echoed this thirst for understanding, whether in the East or West. It wasn’t just about obtaining answers; it celebrated the journey of arriving at them. The process, probing, introspection, and subsequent revelations hold a revered spot in our collective memory. The reverence with which we’ve held questions, as seen through the words of philosophers, poets, and thinkers, showcases the ceaseless human spirit in its quest for knowledge.

In today’s interconnected world, the legacy of these inquiries remains ever-pertinent. We live in an era of information, a double-edged sword presenting knowledge and misinformation. As we grapple with this deluge, the skills of discernment and critical inquiry, inherited from our ancestors, are invaluable. It’s no longer just about seeking answers but about discerning the truths among many voices.

With the current rise in misinformation and fake news, a sharpened sense of questioning becomes our compass, guiding us through the mazes of contemporary challenges. By honouring the traditions of the past and adapting them to our present, we continue our timeless pursuit of truth, ensuring that the pulse of inquiry beats strongly within us.

Understanding the Socratic Method

Having recognised the age-old reverence for inquiry, it becomes imperative to explore one of its most pivotal techniques: the Socratic method. Socrates, widely regarded as a paragon of wisdom, believed that life’s true essence lies in perpetual self-examination and introspection. His approach was unique in its time, as he dared to challenge societal norms and assumptions. When proclaimed the wisest man in Greece, he responded not with complacency but with probing inquiry.

The Socratic method transcends a mere question-answer paradigm. Instead, it becomes a catalyst, prompting deep reflection. This dialectical technique fosters enlightenment, not by spoon-feeding answers but by kindling the flames of critical thinking and understanding. The beauty of this method rests not solely in the answers it might yield, but in the journey of introspection and dialogue it necessitates.

Beyond philosophical discourses, this method resonates powerfully in contemporary educational spheres. It underscores that genuine knowledge transcends rote memorisation, emphasising comprehension and enlightenment. This reverence for knowledge stresses the imperative of recognising our limitations fostering an ethos where learning is ceaseless and dynamic.

In our information-saturated age, the Socratic method’s principles are not just philosophical musings but indispensable. According to Statistica, only about 26% of Americans feel adept at discerning fake news, while a concerning 90% inadvertently propagate misinformation. Herein lies the true power of the Socratic approach. It teaches us discernment, evaluation, and the courage to seek clarity continuously. By integrating this method into our lives, we are better equipped to navigate our intricate world, fostering lives marked by clarity, purpose, and profound understanding.

Why the question often surpasses the answer

Having delved into the rich tapestry of historical inquiry and the transformative power of the Socratic method, one may wonder: Why such an emphasis on the question rather than the answer?

We are often trained to seek definite conclusions throughout our educational journey and societal conditioning. Yet, as Socrates demonstrated through his dialogues, there’s profound wisdom in embracing the exploration inherent in questioning. His discussions rarely aimed for definitive answers, suggesting that the reflective process, rather than the conclusion, held deeper significance.

Imagine a complex puzzle. While the completed picture might offer satisfaction, aligning each piece, understanding its intricacies, and appreciating its nuances truly enriches the experience. Similarly, questions, even those without clear-cut resolutions, can expand our horizons, provoke self-assessment, and challenge our preconceived notions. This process broadens our perspectives and fosters a more holistic understanding of our surroundings.

By valuing the act of questioning, we equip ourselves with the tools to navigate ambiguity, confront our limitations, and engage with the world more thoughtfully and profoundly.

The Socratic Method in contemporary frameworks

Socratic questioning involves a disciplined and thoughtful dialogue between two or more people, and its methodologies, rooted in ancient philosophy, remain instrumental in today’s diverse contexts. In the realm of academia, especially within higher education, this collaborative form of questioning is a cornerstone. Educators don’t merely transfer information; they challenge students with introspective questions, compelling them to reflect, engage, and critically evaluate the content presented.

Beyond the classroom, the applicability of the Socratic method stretches wide. Business environments, such as boardrooms and innovation brainstorming sessions, harness the power of Socratic dialogue, pushing participants to confront and rethink assumptions. Professionals employ this method in therapeutic and counselling to guide clients in introspective exploration, encouraging clarity and self-awareness.

Through its emphasis on continuous dialogue, deep reflection, and the mutual pursuit of understanding, this age-old method remains a beacon, guiding us as we navigate the ever-evolving complexities of our modern world.

Conclusion: the timeless art of inquiry

From the cobbled streets of ancient Athens to contemporary classrooms, boardrooms, and counselling sessions, the enduring legacy of the Socratic method attests to the potent force of inquiry. By valuing the exploratory process as much as, if not more than, the final insight, we pave a path towards richer understanding, intellectual evolution, and the limitless possibilities of human achievement.

In today’s deluge of data and information, the allure of swift answers is undeniable. Yet, Socrates’ practice reminds us of the transformative power held in the act of questioning. Adopting such a mindset, as this iconic philosopher once did, extends an open invitation to a life punctuated by curiosity, wonder, and unending discovery.

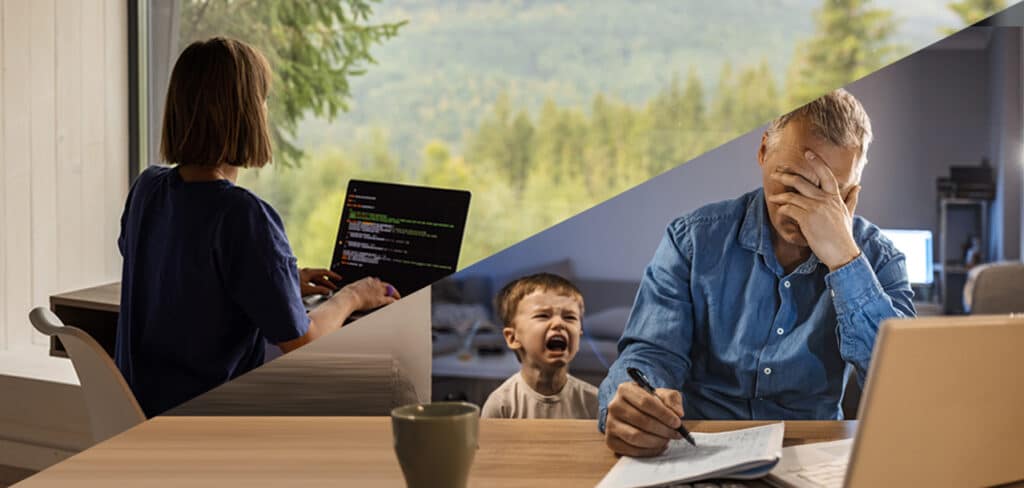

Depending on who you listen to working from home is either proof of a declining work ethic – evidence of and contributor to a global malaise that is hampering productivity, decimating work culture and amplifying isolation and laziness – or it’s a much-needed break from overzealous corporate control, finally giving workers the autonomy to do their jobs when, where and how they want to, with some added benefits to well-being, job satisfaction and quality of work baked in.

Three years on from the pandemic that made WFH models ubiquitous, the practice’s status is oddly divisive. CEOs malign it. Workers love it. Like most statements around WFH, that analysis is over simplistic. So what’s the actual truth: is WFH good, bad or somewhere in between?

The numbers

Before the pandemic Americans spent 5% of their working time at home. By spring 2020 the figure was 60% [1]. Over the following year, it declined to 35% and is currently stabilised at just over 25% [2]. A 2022 McKinsey survey found that 58% of employed respondents have the option to work from home for all or part of the week [3].

In the UK, according to data released by the Office for National Statistics in February, between September 2022 and January 2023, 16% of the workforce still worked solely from home, while 28% were hybrid workers who split their time between home and the office [4]. Meanwhile, back in 1981, only 1.5% of those in employment reported working mainly from home [5].

The trend is clear. Over the latter part of the 20th century and earliest part of the 21st, homeworking increased – not surprising given the advancements to technology over this period – but the increase wasn’t drastic. With Covid, it surged, necessarily, and proved itself functional and convenient enough that there was limited appetite to put it back in the box once the worst of the crisis was over.

The sceptics

Working from home “does not work for younger people, it doesn’t work for those who want to hustle, it doesn’t work in terms of spontaneous idea generation” and “it doesn’t work for culture.” That’s according to JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon [6]. People who work from home are “phoning it in” according to Elon Musk [7]. In-person engineers “get more done,” says Mark Zuckerberg, and “nothing can replace the ability to connect, observe, and create with peers that comes from being physically together,” says Disney CEO Bob Iger [8].

Meanwhile, 85% of employees who were working from home in 2021 said they wanted a hybrid approach of both home and office working in future [9]. It seems there’s a clash, then, between the wants of workers and the wants of their employers.

Brian Elliott, who previously led Slack’s Future Forum research consortium and now advises executive teams on flexible work arrangements, puts the disdain for WFH from major CEOs down to “executive nostalgia” [10].

Whatever the cause, and whether merited or not, feelings are strong – on both sides. Jonathan Levav, a Stanford Graduate School of Business professor who co-authored a widely cited paper finding that videoconferencing hampers idea generation, received furious responses from advocates of remote-work. “It’s become a religious belief rather than a thoughtful discussion,” he says [11].

In polarised times, it seems every issue becomes black or white and we must each choose a side to buy into dogmatically. Given the divide seems to exist between those at the upper end of the corporate ladder and those below, it’s especially easy for the WFH debate to fall into a form of tribal class warfare.

Part of the issue is that each side can point to studies showing the evident benefits of their point of view and the evident issues with their opponents. It’s the echo-chamber effect. Some studies show working from home to be more productive. Others show it to be less. Each tribe naturally gravitates to the evidence that best suits their argument. Nuance lies dead on the roadside.

Does WFH benefit productivity?

The jury is still out.

An Owl Labs report on the state of remote work in 2021 found that of those working from home during 2021, 90% of respondents said they were at least at the same productivity level working from home compared to the office and 55% said they worked more hours remotely than they did at the office [12].

On the other end of the spectrum, a paper from Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom, which reviewed existing studies on the topic, found that fully remote workforces on average had a reduced productivity of around 10% [13].

Harvard Business School professor Raj Choudhury, looking into government patent officers who could work from anywhere but gathered in-person several times a year, championed a hybrid approach. He found that teams who worked together between 25% and 40% of the time had the most novel work output – better results than those who spent less or more time in the office. Though he said that the in-person gatherings didn’t have to be once a week. Even just a few days each month saw a positive effect [14].

It’s not just about productivity though. Working from home can have a negative impact on career prospects if bosses maintain an executive nostalgia for the old ways of working. Studies show that proximity bias – the idea that being physically near your colleagues is an advantage – persists. A survey of 800 supervisors by the Society for Human Resource Management in 2021 found that 42% percent said that when assigning tasks, they sometimes forget about remote workers [15].

Similarly, a 2010 study by UC Davis professor Kimberly Elsbach found that when people are seen in the office, even when nothing is known about the quality of their work, they are perceived as more reliable and dependable – and if they are seen off-hours, more committed and dedicated [16].

Other considerations

It’s worth noting other factors outside of productivity that can contribute to the bottom line. As Bloom states, only focusing on productivity is “like saying I’ll never buy a Toyota because a Ferrari will go faster. Well, yes, but it’s a third the price. Fully remote work may be 10% less productive, but if it’s 15% cheaper, it’s actually a very profitable thing to do” [17].

Other cost-saving benefits of a WFH or hybrid work model include potentially allowing businesses to downsize their office space and save on real estate. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) estimated that increases in remote work in 2015 saved it $38.2 million [18].

Minimising the need for commuting also helps ecologically. The USPTO estimates that in 2015 its remote workers drove 84 million fewer miles than if they had been travelling to headquarters, reducing carbon emissions by more than 44,000 tons [19].

A hybrid model

Most businesses now tend to favour a hybrid model. Productivity studies, including Bloom’s that found the 10% productivity drop from fully remote working, tend to concede there’s little to no difference in productivity between full-time office staff and hybrid workers. 47% of American workers prefer to work in a hybrid model [20]. In the UK, it’s 58% [21]. McKinsey’s American Opportunity Survey found that when given the chance to work flexibly, 87% of people take it [22].

However, as Annie Dean, whose title is “head of team anywhere” at software firm Atlassian, notes: “For whatever reason, we keep making where we work the lightning rod, when how we work is the thing that is in crisis” [23].

Choudhary backs this up, saying, “There’s good hybrid – and there’s terrible hybrid” [24]. It’s not so much about the model as the method. Institutions that put the time and effort into ensuring their home and hybrid work systems are well-defined and there’s still room for discussion, training and brainstorming – all the things that naysayers say are lost to remote working – are likely to thrive.

That said, New Yorker writer Cal Newport points out that firms that have good models in place (what he calls “agile management”) are few and far between. Putting such structures in place is beyond the capability of most organisations. “For those not benefiting from good (“Agile”) management,” he writes, “the physical office is a necessary second-best crutch to help firms get by, because they haven’t gotten around to practising good management [25].”

The future

Major CEOs may want a return to full-time office structures, but a change seems unlikely. You can’t put the genie back in the bottle. Home and hybrid working is popular with employees, especially millennials and Gen Z. As of 2022 millennials were the largest generation in the workforce [26]; their needs matter.

The train is only moving in one direction – no amount of executive nostalgia is going to get it to turn back. It seems a hybrid model is the future, and a healthy enough compromise.

References

[1] https://www.economist.com/special-report/2021/04/08/the-rise-of-working-from-home

[2] https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2023/03/29/why-working-from-home-is-here-to-stay/

[3] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/real-estate/our-insights/americans-are-embracing-flexible-work-and-they-want-more-of-it

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/feb/14/working-from-home-revolution-hybrid-working-inequalities

[5] https://wiserd.ac.uk/publication/homeworking-in-the-uk-before-and-during-the-2020-lockdown/

[6] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenamcgregor/2023/08/19/the-war-over-work-from-home-the-data-ceos-and-workers-need-to-know/

[7] https://hbr.org/2023/07/tension-is-rising-around-remote-work

[8] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenamcgregor/2023/08/19/the-war-over-work-from-home-the-data-ceos-and-workers-need-to-know/

[9] https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/businessandindividualattitudestowardsthefutureofhomeworkinguk/apriltomay2021

[10]

https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenamcgregor/2023/08/19/the-war-over-work-from-home-the-data-ceos-and-workers-need-to-know/

[11] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenamcgregor/2023/08/19/the-war-over-work-from-home-the-data-ceos-and-workers-need-to-know/

[12] https://owllabs.com/state-of-remote-work/2021/

[13] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenamcgregor/2023/08/19/the-war-over-work-from-home-the-data-ceos-and-workers-need-to-know/

[14] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenamcgregor/2023/08/19/the-war-over-work-from-home-the-data-ceos-and-workers-need-to-know/

[15] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenamcgregor/2023/08/19/the-war-over-work-from-home-the-data-ceos-and-workers-need-to-know/

[16] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenamcgregor/2023/08/19/the-war-over-work-from-home-the-data-ceos-and-workers-need-to-know/

[17]

https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenamcgregor/2023/08/19/the-war-over-work-from-home-the-data-ceos-and-workers-need-to-know/

[18] https://hbr.org/2020/11/our-work-from-anywhere-future#:~:text=Benefits%20and%20Challenges,of%20enhanced%20productivity%20and%20engagement

[19] https://hbr.org/2020/11/our-work-from-anywhere-future#:~:text=Benefits%20and%20Challenges,of%20enhanced%20productivity%20and%20engagement.

[20] https://siepr.stanford.edu/publications/policy-brief/hybrid-future-work#:~:text=Hybrid%20is%20the%20future%20of%20work%20Key%20Takeaways,implications%20of%20how%20and%20when%20employees%20work%20remotely.

[21] https://mycreditsummit.com/work-from-home-statistics/

[22] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/real-estate/our-insights/americans-are-embracing-flexible-work-and-they-want-more-of-it

[23] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenamcgregor/2023/08/19/the-war-over-work-from-home-the-data-ceos-and-workers-need-to-know/

[24] https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenamcgregor/2023/08/19/the-war-over-work-from-home-the-data-ceos-and-workers-need-to-know/

[25] https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2023/03/29/why-working-from-home-is-here-to-stay/

[26] https://www.forbes.com/sites/theyec/2023/01/10/whats-the-future-of-remote-work-in-2023/

Introduction

Originally published in 2013, Ichiro Kishimi and Fumitake Koga’s The Courage to be Disliked quickly became a sensation in its authors’ native Japan. Its English language translation followed suit with more than 3.5 million copies sold worldwide.

The book is often shelved in the ‘self-help’ category, in large part due to its blandly overpromising subheading: How to free yourself, change your life and achieve real happiness. In truth it would be better suited to the philosophy or psychology section. The book takes the form of a discussion between a philosopher and an angsty student. The student is unhappy with his life and often with the philosopher himself, while the philosopher is a contented devotee of Adlerian psychology, the key points of which he disseminates to the student over the course of five neatly chunked conversations. His proposed principles offer sound advice for life in general but also prove useful when integrated into a business setting.

Adlerian Psychology

Alfred Adler was an Austrian born psychotherapist and one of the leading psychological minds of the 20th century. Originally a contemporary of Freud’s, the two soon drifted apart. In many ways Adler’s theories can be defined in opposition to his old contemporary; they are anti-Freudian at their core. Freud is a firm believer that our early experiences shape us. Adler is of the view that such sentiments strip us of autonomy in the here and now, seeing Freud’s ideas as a form of determinism. He instead proffers:

No experience is in itself a cause of our success or failure. We do not suffer from the shock of our experiences – the so-called trauma – but instead, we make out of them whatever suits our purposes. We are not determined by our experiences, but the meaning we give them is self-determining.

Essentially, then, the theories are reversed. Adler posits that rather than acting a certain way in the present because of something that happened in their past, people do what they do now because they chose to, and then use their past circumstances to justify the behaviour. Where Freud would make the case that a recluse doesn’t leave the house because of some traumatic childhood event, for example, Adler would argue that instead the recluse has made a decision to not leave the house (or even made it his goal not to do so) and is creating fear and anxiety in order to stay inside.

The argument comes down to aetiology vs teleology. More plainly, assessing something’s cause versus assessing its purpose. Using Adlerian theory, the philosopher in the book tells the student that: “At some stage in your life you chose to be unhappy, it’s not because you were born into unhappy circumstances or ended up in an unhappy situation, it’s that you judged the state of being unhappy to be good for you”. Adding, in line with what David Foster-Wallace referred to as the narcissism of self-loathing, that: “As long as one continues to use one’s misfortune to one’s advantage in order to be ‘special’, one will always need that misfortune.”

Adler in the workplace: teleology vs aetiology

An example of the difference in these theories in the workplace could be found by examining the sentence: “I cannot work to a high standard at this company because my boss isn’t supportive.” The viewpoint follows the cause and effect Freudian notion: your boss is not supportive therefore you cannot work well. What Adler, and in turn Kishimi and Koga, argue is that you still have a choice to make. You can work well without the support of your boss but are choosing to use their lack of support as an excuse to work poorly (which subconsciously was your aim all along).

This is the most controversial of Adler’s theories for a reason. Readers will no doubt look at the sentence and feel a prescription of blame being attributed to them. Anyone who has worked with a slovenly or uncaring boss might feel attacked and argue that their manager’s attitude most certainly did affect the quality of their work. But it’s worth embracing Adler’s view, even if just to disagree with it. Did you work as hard as you could and as well as you could under the circumstances? Or did knowing your boss was poor give you an excuse to grow slovenly too? Did it make you disinclined to give your best?

Another example in the book revolves around a young friend of the philosopher who dreams of becoming a novelist but never completes his work, citing that he’s too busy. The theory the philosopher offers is that the young writer wants to leave open the possibility that he could have been a novelist if he’d tried but he doesn’t want to face the reality that he might produce an inferior piece of writing and face rejection. Far easier to live in the realm of what could have been. He will continue making excuses until he dies because he does not want to allow for the possibility of failure that reality necessitates.

There are many people who don’t pursue careers along similar lines, staunch in the conviction that they could have thrived if only the opportunity had arisen without ever actively seeking that opportunity themselves. Even within a role it’s possible to shrug off this responsibility, saying that you’d have been better off working in X role in your company if only they had given you a shot, or that you’d be better off in a client-facing position rather than being sat behind a desk doing admin if only someone had spotted your skill sets and made use of them. But without asking for these things, without actively taking steps towards them, who does the responsibility lie with? It’s a hard truth, but a useful one to acknowledge.

Adler in the workplace: All problems are interpersonal relationship problems

Another of the key arguments in the book is that all problems are interpersonal relationship problems. What that means is that our every interaction is defined by the perception we have of ourselves versus the perception we have of whomever we are dealing with. Adler is the man who coined the term “inferiority complex”, and that factors into his thinking here. He spoke of two categories of inferiorities: objective and subjective. Objective inferiorities are things like being shorter than another person or having less money. Subjective inferiorities are those we create in our mind, and make up the vast majority. The good news is that “subjective interpretations can be altered as much as one likes…we are inhabitants of a subjective world.”

Adler is of the opinion that: “A healthy feeling of inferiority is not something that comes from comparing oneself to others; it comes from one’s comparison with one’s ideal self.” He speaks of the need to move from vertical relationships to horizontal ones. Vertical relationships are based in hierarchy. If you define your relationships vertically, you are constantly manoeuvring between interactions with those you deem above you and those you deem below you. When interacting with someone you deem above you on the hierarchical scale, you will automatically adjust your goalposts to be in line with their perceptions rather than defining success or failure on your own terms. As long as you are playing in their lane, you will always fall short. “When one is trying to be oneself, competition will inevitably get in the way.”

Of course in the workplace we do have hierarchical relationships. There are managers, there are mid-range workers, there are junior workers etc. The point is not to throw away these titles in pursuit of some newly communistic office environment. Rather it’s about attitude. If you are a boss, do you receive your underlings’ ideas as if they are your equal? Are you open to them? Or do you presume that your status as “above” automatically means anything they offer is “below”? Similarly if you are not the boss, are you trying to come up with the best ideas you can or the ones that you think will most be in-line with your boss’ pre-existing convictions? Obviously there’s a balance here – if you solely put forward wacky, irrelevant ideas that aren’t in line with your company’s ethos and have no chance of success then that’s probably not helpful, but within whatever tramlines your industry allows you can certainly get creative and trust your own taste rather than seeking to replicate someone else’s.

Pivotal to this is whether you are willing to be disagreed with and to disagree with others or are more interested in pleasing everyone, with no convictions of your own. This is where the book’s title stems from. As it notes, being disliked by someone “is proof that you are exercising your freedom and living in freedom, and a sign that you are living in accordance with your own principles…when you have gained that courage, your interpersonal relationships will all at once change into things of lightness.”

Adler in the workplace: The separation of tasks

The separation of tasks is pivotal to Adlerian theory and interpersonal relationships. It is how Adler, Kishimi and Koga suggest one avoids falling into the trap of defining oneself by another’s expectations. The question one must ask themselves at all times, they suggest, is: Whose task is this? We must focus solely on our own tasks, not letting anyone else alter them and not trying to alter anyone else’s. This is true for both literal tasks – a piece of work, for example – but also more abstract ideas. For example, how you dress is your task. What someone else thinks of how you dress is theirs. Do not make concessions to their notions (or your perceptions of what their notions might be) and do not be affected by what they think for it is not your task and therefore not yours to control.

This idea that we allow others to get on with their own tasks is crucial to Adler’s belief in how we can live rounded, fulfilling lives. The philosopher argues that the basis of our interpersonal relationships – and as such our own happiness – is confidence. When the boy asks how the philosopher defines the “confidence” of which he speaks, he answers:

It is doing without any set conditions whatsoever when believing in others. Even if one does not have sufficient objective grounds for trusting someone, one believes. One believes unconditionally without concerning oneself with such things as security. That is confidence.

This confidence is vital because the book’s ultimate theory is that community lies at the centre of everything. The awareness that “I am of use to someone” both allows one to act with confidence in their own life, have confidence in others, and to not be reliant on the praise of others. The reverse is true too. As Kishimi and Koga state, “A person who is obsessed with the desire for recognition does not have any community feeling yet, and has not managed to engage in self-acceptance, confidence in others, or contribution to others.” Once one possesses these things, the need for external recognition will naturally diminish.

For high-level employees, then, it’s important to set a tone in the workplace that allows colleagues to feel that they are of use. But as the book dictates, do not do this by fake praise – all that will do is foster further need for recognition (“Being praised essentially means that one is receiving judgement from another person as ‘good.’”) Instead, foster this atmosphere by trusting them, showing confidence.

The courage to be disliked

The Courage to be Disliked is at odds with many of the accepted wisdoms of the day. Modern cultural milieu suggests that we should be at all times accepting and validating others’ trauma as well as our own. Many may even find solace in this approach and find that it suits them best. But there is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to fostering a successful workplace and even less so when it comes to leading a fulfilling life. For anyone who feels confined by the idea that there are parameters around what they can achieve and are capable of because of some past event or some subjective inferiority that has been harboured too long, perhaps look at those interpersonal relationships, perhaps find the courage to be disliked, and in doing so hope to find a community that you’re willing to support as much as it supports you. There is no need to be shackled to whatever mythos you’ve internally created.

As the book states: “Your life is not something that someone gives you, but something you choose yourself, and you are the one who decides how you live…No matter what has occurred in your life up to this point, it should have no bearing at all on how you live from now on.”

References

Kishimi, Ichiro & Koga, Fumitake. The Courage to Be Disliked: How to Free Yourself, Change your Life and Achieve Real Happiness. Bolinda Publishing Pty Ltd. 2013.

Introduction

Consider a simple yet profound question: What does your work mean to you? Is it merely a task to be completed, or does it resonate with a deeper purpose in your life?

Viktor Frankl, a prominent Austrian psychiatrist and philosopher, grappled with these very questions, evolving them into a broader exploration of life’s meaning. Drawing from his harrowing experiences in Nazi concentration camps, he developed logotherapy—a form of psychotherapy that centres around the search for meaning and purpose. Through logotherapy, Frankl illuminated the idea that life’s essence can be found not just in joyous moments but also in love, work, and our attitude towards inevitable suffering. This pioneering approach underscores personal responsibility and has offered countless individuals a renewed perspective on fulfilment, even in the face of daunting challenges.

In this piece, we delve into the intricacies of Frankl’s teachings, exploring the symbiotic relationship he identified between work and our quest for meaning.

A Holistic Approach to Life and Work

In his seminal work, ‘Man’s Search for Meaning,’ Viktor Frankl delved deeply into the multifaceted nature of human existence. He eloquently described the myriad pathways through which individuals uncover meaning. For Frankl, while work or ‘doing’ is undoubtedly a significant avenue for deriving meaning, it isn’t the only one. He emphasised the value of love, relationships, and our responses to inevitable suffering. Through this lens, he offered a panoramic view of life, advocating for a holistic perspective where meaning is not strictly tethered to our work but is intricately woven through all our experiences and interactions.

Progressing in his exploration, Frankl sounded a note of caution about the perils of letting work become an all-consuming end in itself. He drew attention to the risks of burnout and existential exhaustion when one’s sense of purpose is confined solely to one’s occupation or the relentless chase for wealth. To Frankl, an overemphasis on materialistic achievements could inadvertently lead individuals into what he termed an ‘existential vacuum’ – a state where life seems starkly devoid of purpose. He argued that in our quest for success, we must continually seek a deeper, more intrinsic purpose. Otherwise, we risk being blinded by life’s profound significance and richness beyond material gains.

Delving deeper into the realm of employment, Frankl confronted the psychological and existential challenges of unemployment. He noted that without the inherent structure and purpose provided by work, many individuals grapple with a profound sense of meaninglessness. This emotional and existential void often manifests in a diminishing sense of significance towards time, leading to dwindling motivation to engage wholeheartedly with the world. The ‘existential vacuum’ emerges again, casting its shadow and enveloping individuals in feelings of purposelessness.

Yet, Frankl’s observations were not merely confined to the challenges. He beautifully illuminated the resilience and fortitude of certain individuals, even in the face of unemployment. He showcased how, instead of linking paid work directly with purpose, some found profound meaning in alternative avenues such as volunteer work, creative arts, education, and community participation.

Frankl firmly believed that the essence of life’s meaning often lies outside the traditional realms of employment. To drive home this perspective, he recounted poignant stories, such as that of a desolate young man who unearthed profound purpose and reaffirmed his belief in his intrinsic value by preventing a distressed girl from taking her life. Such acts, as illustrated by Frankl, highlight the boundless potential for a meaningful existence, often discovered in genuine moments of human connection.

Work as an Avenue for Meaning and Identity

Viktor Frankl’s discourse on work transcended the common notions of duty and obligation. For him, work was more than a mere means to an end; it was a potent avenue to unearth meaning and articulate one’s identity. Frankl posited that when individuals align their work with their intrinsic identity—encompassing all its nuances and dimensions—they move beyond merely working to make a living. Instead, they find themselves working with a purpose.

This profound idea stems from his unwavering belief that our work provides us with a unique opportunity. Through it, we can harness our individual strengths and talents, channelling them to create a meaningful and lasting impact on the world around us.

In line with modern philosophical thought, which views work as a primary canvas for self-expression and self-realisation, Frankl also recognised its significance. He believed that work could serve as a pure channel, finely tuned to our unique skills, passions, and aspirations. This deep sense of accomplishment and fulfilment from one’s chosen profession, he asserted, is invaluable. However, Frankl also emphasised the importance of seeing the broader picture. While careers undeniably play a significant role in our lives, they are but a single facet in our ongoing quest for meaning.

Frankl reminds us that while our careers are integral to our lives, the quest for meaning isn’t imprisoned within their boundaries. He believed the core of true meaning emerges from our deep relationships, our natural capacity for empathy, and our virtues. These treasures of life, he asserted, can be manifested both within the confines of our workplace and beyond.

The True Measure of Meaning Through Work

For Viktor Frankl, our professional lives brim with potential for fulfilment. Yet, fulfilment wasn’t solely defined by accolades. Instead, it was about aligning our work with our deepest values and desires. It wasn’t just the milestones that mattered but how they resonated with our core beliefs.

Frankl’s logotherapy reshapes our perception of work, emphasising that even mundane tasks can hold significance when approached with intent. With the right mindset, every job becomes a step in our journey for meaning.

In Frankl’s writings, he weaves together tales of profound significance—a young man’s transformative act of kindness, a narrative not strictly tethered to work’s traditional realm. Yet, these stories anchor a timeless truth: In every endeavour, whether grand or humble, lies the potential for unparalleled meaning. Here, work isn’t just about designated roles—it becomes an evocative stage where profound moments play out. Beyond job titles and tasks, the depth, sincerity, and fervour we infuse into each act truly capture the essence of meaningful work.

Finding Fulfilment in Every Facet

Viktor Frankl’s profound insights into the human pursuit of meaning provide a distinctive lens through which we can evaluate both our daily tasks and life’s most pivotal moments. Through his exploration—whether addressing the ordinariness of daily life or the extremities of crisis—Frankl illuminated the profound interconnectedness of work and personal identity. He posited that our professions, while significant, are fragments of a vast tapestry that constitute human existence.

Navigating the journey of life requires continual adjustments to our perceptions of success and meaning. While our careers and professional achievements are significant, true fulfilment goes beyond these confines. It’s woven into our human experiences, the bonds we nurture, the challenges we face, and the joys we hold dear.

Frankl’s pioneering work in logotherapy urges us to approach life with intention and purpose. He beckons us to see the value in every moment, task, and human connection. As we delve into our careers and strive for success, aligning not just with outward accomplishments but with the very essence of who we are is vital.

Introduction

Coaching has long been viewed as a premium service, frequently offered only to the upper echelons of organisations, the C-suite executives. The potential benefits of coaching in enhancing leadership skills, strategic thinking, and overall effectiveness are well-documented (Gawande, 2011; Coutu & Kauffman, 2009). However, current research also underscores its broader utility across all tiers of an organisation, promoting it as an indispensable instrument for comprehensive personal and professional development (Grover & Furnham, 2016; Wang, Qing, et al., 2021).

Contemplating a world where coaching benefits could be accessed by every individual within an organisation, irrespective of their position, is invigorating. Envision a Chief Coaching Officer (CCO) guiding this transformation, meticulously integrating coaching into every facet of the organisational structure. Such progressive thinking could trigger a paradigm shift in the corporate landscape.

Coaching is now in the top three tools for modern organisations. There are a number of global organisations who are actively utilising coaching – those that are show marked individual and team improvements.

Coaching Beyond Conventional Domains

Atul Gawande’s (2011) illuminating article “Personal Best” and Ted Talk narrates how the power of coaching can transcend beyond traditional spaces into unexpected realms like the operating theatre. He invites a retired colleague to observe his surgical techniques and offer coaching, effectively bridging the coaching principles of sports or performing arts with the medical field. This compelling narrative is a testament to the universality of coaching, emphasising its potential for ongoing self-improvement across various professional disciplines.

Dispelling Misconceptions Around Coaching

To achieve an effective rollout of a comprehensive coaching strategy, we need to challenge the pre-existing association of coaching with performance improvement or the resolution of performance issues, particularly outside the C-suite. Coaching should be viewed as something other than a remedial measure but as a proactive tool for fostering personal and professional growth. This proactive view promotes an organisational culture where coaching becomes a regular aspect of professional development rather than a response to performance deficiencies.

Expanding the Horizon of Coaching

Consider an early career employee mastering technical skills while being coached to negotiate broader career challenges. Or a mid-level manager augmenting their leadership prowess through a customised development journey. The utility of coaching extends beyond conventional confines, offering numerous benefits, including amplified self-awareness, goal attainment, and improved stress management (Grant, 2013; Bozer & Sarros, 2014).

Introducing the Chief Coaching Officer

The advent of a Chief Coaching Officer (CCO) could revolutionise coaching. By nurturing a coaching culture within the organisation, a CCO can make coaching accessible to all, from entry-level professionals to senior executives. The CCO’s responsibilities would include overseeing the execution of coaching programmes, designing an overarching coaching strategy, and ensuring effective resource allocation. Crucially, the CCO would assess the impact of these initiatives on individual and organisational performance, thereby validating the effectiveness of the coaching interventions.

Addressing Potential Hurdles

The transition towards a coaching culture does not come without its challenges. These range from financial constraints and identifying apt coaches to the potential discomfort of professionals who may be reluctant to expose themselves to scrutiny. Nevertheless, these hurdles are not insurmountable. Retirement, for instance, need not symbolise the end of one’s career; the wealth of experience accumulated by retirees could be channelled into coaching roles. Furthermore, investing in coaching can yield significant returns, not just in the form of avoided mistakes but also through augmented performance (Gawande, 2011).

The Final Word

In our ever-competitive and rapidly evolving world, organisations must recognise the potential benefits of expanding the scope of coaching. Empirical evidence supports its effectiveness as a developmental intervention (Grover & Furnham, 2016; Sharma, 2017; Wang, Qing, et al., 2021). Adopting an organisation-wide approach to coaching can catalyse individual potential and drive company-wide growth. The appointment of a Chief Coaching Officer can be a strategic move towards fostering a culture of continuous learning and improvement. Ultimately, the goal is to enable every professional to achieve their personal best, regardless of their position or field.

References

Coutu, D., & Kauffman, C. (2009). What can coaches do for you? Harvard Business Review, 87(1), 92–97.

Gawande, A. (2011). Personal best. The New Yorker, October, 3.

Grover, S., & Furnham, A. (2016). Coaching as a developmental intervention in organisations: A systematic review of its effectiveness and the mechanisms underlying it. PloS one, 11(7), e0159137.

Bozer, G., & Sarros, J. C. (2012). Examining the effectiveness of executive coaching on coachees’ performance in the Israeli context. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 10(1), 14-32.

Grant, A. M. (2013). The efficacy of executive coaching in times of organisational change. Journal of Change Management, 13(4), 411-429.

Sharma, P. (2017). How coaching adds value in organisations-The role of individual level outcomes. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching & Mentoring, 15.

Wang, Q., Lai, Y., Xu, X., & McDowall, A. (2021). The effectiveness of workplace coaching: a meta-analysis of contemporary psychologically informed coaching approaches. Journal of Work-Applied Management.

Introduction

Clusters, as conceptualised by Michael Porter (1990), have been central in economic theory. Geographically concentrated interconnected companies within similar industries have spurred economic growth and driven innovation. Silicon Valley’s technology hub, Wall Street’s finance focus, and Milan’s fashion hotspot are just a few instances of this clustering phenomenon.

Although economic and geographical clustering offers intriguing insights, I’m particularly interested in applying this concept to the microcosm of individual organisations – their teams. Could the “cluster” effect potentially apply to the human aspects of businesses?

What is a team cluster?

Based on principles of organisational psychology, a “team cluster” is a group of people with unique strengths who work together to create an environment that fosters innovation and high performance, according to Sundstrom et al. (2000). This approach differs from the traditional “superstar” model, which relies on one exceptionally talented individual to drive success. Instead, it suggests that a team made up of consistently above-average members is more likely to achieve optimal performance.

The way a team works together is very important in this model (Forsyth, 2018). Adding a superstar could upset the balance of the team and cause conflicts or hard feelings. However, a team that is well-balanced will work well together and have better relationships, leading to better performance. The Galáctico project in Real Madrid which was cancelled in 2007, is an example of this (although there is a new one in development by all accounts).

The power of a strong team can be seen in historical examples, such as Walt Disney Studios’ ‘Nine Old Men’, a group of animators who worked together to create beloved films like ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’ and ‘Bambi’. This shows how a team with a balance of talent can be more effective than relying on one exceptional individual.

Social loafing

According to a theory called social loafing (Latane et al., 1979), people often put in less effort when they are part of a group, especially if they think that someone else in the group is responsible for most of the success. However, having a well-balanced team ensures that every member’s input is valuable, which decreases the chances of social loafing and leads to better overall performance.

The ground-breaking development of penicillin by Howard Florey, Ernst Boris Chain, and their colleagues at Oxford University exemplifies the power of such a team cluster (Ligon, 2004). Each individual played a vital role in the process, validating the potency of a balanced, collective effort in accomplishing a shared goal.

Training and collaboration

Developing the skills and relationships of team members can strengthen the effectiveness of team clusters. This involves training and development to promote shared understanding, mutual respect, and collaboration within the team, as stated by Salas et al. in 2008. A prime example of this is the COVID-19 vaccine development teams, like the one behind the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, who utilised their diverse skills and knowledge to successfully develop a vaccine through collective effort and collaboration.

Team cluster dynamics

The success of the ENIAC team in history underscores the significance of diversity and equality in teams. The “ENIAC Girls,” a group of six female mathematicians who were among the earliest computer programmers, played a crucial role in the creation of ENIAC, one of the earliest general-purpose computers. This demonstrates the value of utilising various skills and viewpoints, as well as the power of inclusiveness in optimising team performance.

The concept of the team cluster model can be applied in different fields, including sports. However, the dynamics may differ due to the unique nature of athletic performance. Nevertheless, the idea remains valid that a team with a good balance of contributions from each member often performs better than a team focused on one superstar, as proven by Fransen et al. in 2015.

Leadership’s role in team clusters

Creating effective team clusters requires intentional development and management. Encouraging self-development and peer-to-peer learning can raise the team’s overall competency level (Decuyper et al., 2010). Additionally, it’s important to nurture an environment where team members feel valued and understand their contribution to the overall goal. Leadership plays a crucial role in creating a culture that values collaboration, continuous learning, and collective success over individual brilliance.

Conclusion

In conclusion, team clusters are effective because they bring together a diverse range of skills, encourage collaboration, and promote continuous learning and development. By combining these elements, organisations can use team clusters to improve innovation and performance. In short, the team cluster model shows that working together can achieve more than working alone.

References

Decuyper, S., Dochy, F., & Van den Bossche, P. (2010). Grasping the dynamic complexity of team learning: An integrative model for effective team learning in organisations. Educational Research Review, 5(2), 111-133.

Fransen, K., Vanbeselaere, N., De Cuyper, B., Vande Broek, G., & Boen, F. (2015). The myth of the team captain as principal leader: extending the athlete leadership classification within sport teams. Journal of sports sciences, 33(14), 1377-1387.

Forsyth, D. R. (2018). Group Dynamics. Cengage Learning.

Latane, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. (1979). Many Hands Make Light the Work: The Causes and Consequences of Social Loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(6), 822-832.

Ligon, B. L. (2004). Penicillin: Its Discovery and Early Development. Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 15(1), 52-57.

Porter, M. E. (1990). The Competitive Advantage of Nations. Free Press.

Salas, E., Cooke, N. J., & Rosen, M. A. (2008). On teams, teamwork, and team performance: discoveries and developments. Human Factors, 50(3), 540-547.

Sundstrom, E., McIntyre, M., Halfhill, T., & Richards, H. (2000). Work Groups: From the Hawthorne Studies to Work Teams of the 1990s and Beyond. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4(1), 44-67.

Job satisfaction is something we all strive for but by no means all attain. There are various reasons for us to slip into feelings of apathy around our work. We may feel that we are being overlooked and that our skillsets are not being put to good use; we may feel that we are overworked and burnt out or maybe overwhelmed with stress; perhaps a lack of proper work-life balance is impacting our relationship with our friends and family; maybe we don’t fit in with our colleagues or are not contributing as effectively as those around us; or perhaps we even feel that we followed the wrong career path altogether – that the rung of the ladder is less of the issue than the ladder itself. Dissatisfaction is likely to come to all workers at some point. Oftentimes it passes, proving itself to be no more than a tough project or bad day at the office. But if the problem is consistent and/or stifling, action may need to be taken. For those who don’t think the job itself is the problem so much as how they’re handling it, a potential solution is work crafting.

What is work crafting?

Tims et al. (2012)1 define crafting as “the changes employees may make to balance their job demands and job resources with their personal abilities and needs.” The ultimate aim of doing this is to inject work with greater meaning and make it more engaging2. Essentially, without changing our job in any tangible sense – title, deliverables etc. – we ‘craft’ a new, more personalised version of our existing role to make it one that we can better love and thrive in, one “where we still can satisfy and excel in our functions, but which is simultaneously more aligned with our strengths, motives, and passions.”3

Employers may be reading that and biting their nails, but fear not, job crafting is not a license for employees to entirely reconstruct their role, ignoring the aspects of their job they find tedious and unrewarding and replacing them with exclusively grand and shiny tasks that provoke feelings of fulfilment. While management of tasks does factor into work crafting, the more important aspect is based around meaning. As argued by Berg et al. (2008)4, “job crafting theory does not devalue the importance of job designs assigned by managers; it simply values the opportunities employees have to change them.”

Job crafting vs Job design

The CIPD define job design as, “the process of establishing employees’ roles and responsibilities and the systems and procedures that they should use or follow.”5 Its purpose revolves around optimising processes in the workplace to create value and maximise performance. So far, so similar to job crafting. The key difference between the two lies in who is doing the decision-making.

In job design, an employer will be setting boundaries and assigning tasks based on their best understanding of their employees, making a conscious effort to give them work that will reward them and suit their skillsets. In job crafting, it is employees taking the reins. Workers are proactive, and the approach places their wellbeing front and centre. Again, that may be ground that employers are nervous to cede, but job crafting has been linked to better performance, motivation, and employee engagement6.

The three key forms of job crafting

There are various (and varying) approaches to job crafting, but three approaches are most common.

- Task crafting

This is the aspect we have focused on so far, with employees taking a more hands-on approach to their workloads. That could refer to work location (opting to work from home or on a hybrid basis, for example), time management (choosing hours that better suit their life commitments or generally working outside of a traditional 9-5 timeframe), or the tasks themselves (adding or removing tasks from their workload).

The examples around location and working hours are increasingly uncontroversial, especially in the wake of the pandemic. It is the third (employees selecting which tasks they wish to take on) that is the most divisive. Though it should be noted that generally task crafting involves taking on additional tasks rather than removing others. For example, a chef may take it upon themselves to not just serve food but to create aesthetically pleasing plates that enhance a customer’s dining experience. Or a bus driver might decide to give helpful sightseeing advice to tourists along his route7. Potentially an employee working in an administrative capacity may wish to become more engaged with the business, so learn a new software or sales technique, or become more actively involved with clients.

- Relationship crafting

Relationship crafting, unsurprisingly, is all about relationships. Primarily, relationships in the workplace. Having poor interpersonal relationships with colleagues has been found to be a significant contributor to workplace stress8. Conversely, positive work relationships are shown to increase job satisfaction, as well as general mood. By taking a more enthusiastic approach to workplace relationships, whether in or out of office hours, employees are thought to become more engaged with the company and feel more fulfilled in their role.

- Cognitive crafting

Cognitive crafting is all about how we frame the work we do. By assigning meaning to tasks that were conceivably uninspiring or outright deflating before, we can reshape our outlook, instilling our work and lives with a greater sense of purpose, and thus fulfilment. For example, a maid reframing the idea of changing a hotel guest’s bedsheets from a chore to a way to improve someone else’s holiday. Or a customer service worker approaching their clients’ problems like they were a therapist, looking to genuinely make their life better. Framing work tasks in a more positive manner can make work a far more enriching experience, and, unsurprisingly, removing any self-made narratives that what we’re doing is pointless improves mood no end.

Autonomy

The overarching benefit of crafting is the autonomy it affords employees. By giving workers control over how they spend and approach their time, they are able to feel a sense of achievement that might otherwise be lacking. And achievement breeds motivation for more, not to mention the added confidence and sense of worth it affords. A study by Steelcase9 found that when people have greater control over their experiences in the workplace, they become more engaged, which naturally results in greater performance.

Tellingly, studies on the happiness of women in the workplace10 found that there was no difference in mood across participants who worked full-time, part-time or didn’t work at all. Instead, the correlation between the women who were happiest was that they were the ones able to choose their work hours and professions. People have no problem committing to hard work, so long as it’s of their own volition, or offering them a benefit in return, even or especially if that benefit is solely personal fulfilment. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Barbara Ehrenreich, in her book Nickel and Dimed11, found that workers who had little control over the schedules found it disempowering and disabling.

Conclusion

Work-life balance is oft-discussed, and understandably so. We want to be able to enjoy our lives outside of work. This is arguably more important (and harder) now than ever as the lines continue to blur between our homes and workplaces, and our personal and professional devices. Less discussed is how we imbue our work lives with value. A healthy work-life balance should not entail misery during work hours and blissful respite when free. Rather, we should take steps to ensure that our professional days are filled with rewarding moments, whether that be because we’re performing tasks we want to be performing, framing our actions in a healthy, self-loving way, or performing those tasks with people that make it all worthwhile.

Crafting, whether of the task, relationship, or cognitive variety, offers us a way to feel more engaged and fulfilled, to improve our performance, and to take strides towards achieving professional goals we want to conquer. Lost for meaning in your professional life? Give crafting a try.

References

1 Tims, M., Bakker, A., and Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 173–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

2 https://hbr.org/2020/03/what-job-crafting-looks-like

3 Wrzesniewski, A., Berg, J. M., & Dutton, J. E. (2010). Turn the job you have into the job you

want. Harvard Business Review, June, 114-117.

4 Berg, Justin M., et al. “What Is Job Crafting and Why Does It Matter.” Retrieved Form the Website of Positive Organizational Scholarship on April, vol. 15, 2008, p. 2011.

5 https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/strategy/organisational-development/job-design-factsheet#gref

6 https://positivepsychology.com/job-crafting/

7 https://positivepsychology.com/job-crafting/

8 https://positivepsychology.com/positive-relationships-workplace/

9 https://info.steelcase.com/global-employee-engagement-workplace-comparison#key-finding-2

11 APA. Ehrenreich, B. (2010). Nickel and dimed. Granta Books.

Dublin is an inspirational setting. Past and present stories of resilience are written into the city’s fabric and carried by its people. In Merrion Square, there is a unique totem to hopefulness that stands out more than most, the Oscar Wilde memorial monument honouring one of Ireland’s lauded poets and playwrights. Memorably, in Lady Windermere’s Fan, Wilde wrote, ‘We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.’ The power of these lines goes beyond their poetics, positivity, or universality because they touch upon something more profound, the hidden strength of the human psyche.

Measuring optimism

Optimism is a source of scientific inquiry and has been studied extensively to ascertain its physical and psychological benefits. These studies are ongoing, but optimism supplements better health. Research shows that it is associated with contributive behaviours such as being physically active and not smoking (Boehm et al., 2018), a healthy diet score (Hingle et al., 2014), better sleep quality (Sims et al., 2019), and higher composite cardiovascular health scores (ibid, see also Hernandez et al., 2015, 2018). We still need to find out how and why optimism scientifically influences these diagnostics, but we know it yields clear-cut results with empirical certainty.

Other points of influence that may not affect you daily but are impacted by optimism include high capacities for surviving a disease, particularly heart disease (Tindle et al., 2009). Studies also correlate optimism with improved recovery from surgery, broader immunity, positive cancer outcomes, positive pregnancy outcomes, increased pain tolerance, and more stability amid other health concerns. In all of these metrics, those with an optimistic outlook had better results than those who were pessimistic.

Even more impressive is optimism’s association with overall health and longevity. Having a positive outlook is predictive of a greater quality of life (James et al., 2019) and a lower death rate (Rozanski et al., 2019). Optimistic people—whether by disposition, purposeful mindset, or praxis—lead healthier longer lives. Although living better or ageing gracefully does not determine success, health is essential if we approach success as a web of holistic factors related to achieving maximum performance. The evidence is unequivocal; having a positive outlook can boost your physical robustness and provide the platform from which you will most likely achieve consistent success.

What is more, optimism is blind. The data suggests that optimism is a boon regardless of demographic factors such as income level or general health. Maybe this should be less surprising since the positive thinking associated with optimism is also attributed to effective stress management. Stress may not be equal, but it is universal.

Mental health and mentality

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as a ‘state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realise their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community. It is an integral component of health and well-being that underpins our individual and collective abilities to make decisions, build relationships and shape the world we live in.’ Critically, WHO’s definition includes this addendum, ‘Mental health is more than the absence of mental disorders.’ It is more variable and directly assists our health continuum, which, by extension, aids our self-maintenance and performance.

Optimism is intersectional within the body and mind realms it inhabits. It supports psychological well-being, especially during uncertain times when the risk of deteriorating mental health rises. As recently as last year, a statement made by the American Heart Association (AHA) declared, ‘Positive psychological health is also multifaceted and may be characterised by a sense of optimism [my italics], a sense of purpose, gratitude, resilience, positive affect (i.e., positive emotion), and happiness.’

Moreover, mental health’s positive emotional and social dimensions help us foster productive relationships personally and professionally. Being aware of the many unseen components of mental health can help us generate empathetic responses to problems that arise with staff. None of this comes as intuitively as you might presuppose.

Our most recent 1% podcast with Dr Libby Sander identified some gaps in professional culture regarding expectations, an overemphasis upon certain kinds of productivity, boundary setting, burnout, the role of emotional intelligence in leadership, and even the physical space that we work in. I must reiterate Dr Sander’s points. Ultimately, everything is a possible component of our successes and our failures. It is up to us to harness them for our means rather than leave them to become something to be dealt with later.

Pushing out pessimism

Optimism’s counter-force is a balanced critical perspective, not pessimism. The AHA statement outlines that pessimism may be understood as ‘the tendency to expect negative outcomes or by the tendency to routinely explain events in a negative way.’ Just as optimism engenders varied physical and mental health benefits, pessimism is linked to unwanted outcomes such as cardiovascular risk and hopelessness (Pänkäläinen et al., 2019).

Optimism is an active process. Harvard Health Publishing explains that optimism is divided into ‘dispositional’ or ‘explanatory’ modes. Regarding the latter, being optimistic does not mean ignoring less pleasant situations. Accept them and approach unpleasantness more positively and productively. Imagine the best or at least the best possible scenario, not the worst. Be confident you can make it happen. Reconfiguring your visions to even moderately desirable outcomes is beneficial. On these terms, optimism is often a form of honest appraisal and reframing when unexpected or unwanted events occur.

Positivity often begins with self-talk. The thoughts within us can uplift or inhibit us. Much self-talk comes from logic and reason; listen to it. Equally, self-talk comes from misconceptions we create from doubt, if not fear, a lack of information, impossible or unrealistic expectations, and preconceived ideas of what will happen to or against us. These thoughts are not reasonable. Quiet them. Cynicism and downbeat steadfastness are not virtues and spread quickly in a pressurised workplace. If you tend to be pessimistic, you can still learn positive thinking skills. Optimism is part mind state, part mental practice. Identify negative thinking, and try to reduce it. Examples include filtering out what is going well and emphasising what is not, personalising setbacks or making them your fault when they are not, blaming others when it is your fault, expecting the worst possible outcome as opposed to planning for it, magnifying minor setbacks, setting impossible standards so that disappointment becomes a fait accompli, and adopting a polarising view of things as ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ whereby leaving no room for nuance. Envision what you want to happen next or understand what remains possible and focus strictly on actualising it.

Conclusion