Introduction

Sport and business may not seem like natural bedfellows, but just as the former has grown into a fully fledged corporate entity with time, so too has the sporting mindset seeped its way into boardrooms across the western world. The fact that people talk about ‘high performance’ or ‘marginal gains’ is testament to the increased merging of the two.

And it’s not surprising. After all, a lot of the building blocks that will take you far in one are equally applicable to the other. Determination, ambition, work ethic, innovation, the ability to bounce back…list them out like that and there’s no saying which of the two realms you’re referring to. As such, this article will feature some cherry-picked sporting stars and occasions and point to the lessons we in the business world can learn from them.

Mohammad Ali

Where else could we start but with the greatest? In the (extremely unlikely) event that any readers have not heard of Mohammad Ali (formerly Cassius Clay), he was the first boxer to win the world heavyweight championship on three separate occasions. In 1999, Sports Illustrated named him Sportsman of the Century while the BBC named him Sports Personality of the Century. He is arguably the greatest boxer to ever live and certainly the most notorious. As such, we’ll take not one but two lessons from him.

Lesson #1: Sometimes you have to take the hits

In 1974, Ali came up against the unbeaten George Foreman –– to this day the hardest-hitting puncher the sport has ever produced. In what was marketed as ‘The Rumble in the Jungle’, the two fought in the sweltering heat of the Democratic Republic of Congo, lending weight to the autocratic regime of Joseph-Désiré Mobuto in what can be considered an early example of the sportwashing culture that permeates today’s society. Ali was 32. His body could no longer back up his once-defining mantra: float like a butterfly, sting like a bee. People worried for his safety. Foreman could hurt you beyond just defeat.

In a feat of brilliance, Ali did the one thing everyone hoped he wouldn’t: he let Foreman hit him. He hung on the ropes, pulling what we now call the ‘rope-a-dope’, and let the biggest hitter in boxing land blow after blow on his body, over and over again. All Ali guarded was his face while taking endless punishment to the torso. Hit after agonising hit. Pain like you couldn’t imagine. But Ali took it all. Until, eventually, the tactic worked, Foreman tired. In the eighth round, Ali sprung from the ropes and with a left and right to a visibly knackered Foreman’s face shocked the world to regain the Heavyweight title.

There are times in business and in life where things will be hard. They will be painful. So painful that throwing in the towel feels like the easiest option. But it’s not. Sometimes all you have to do through the tough times is hold on, tolerate the pain, knowing that it’s your only chance of making it out the other side victorious. The likelihood is you won’t have planned for that pain –– Ali didn’t; it was something he decided to do in the ring on the night; his coach was as surprised as anyone. But if you’re brave enough to choose to take it, and strong enough to tolerate it, then great things can be born of suffering.

Lesson #2: Principles matter

On June 20, 1967, Muhammad Ali was convicted in Houston for refusing induction in the U.S. armed forces. His accompanying quote when the government attempted to draft him to the fledgling war effort in Vietnam instantly passed into legend: “Man, I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.”

It didn’t take long for Ali to be stripped of his titles and banned from fighting. He lost more than three years of his career protesting a war that history has come to condemn. “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs?” he asked.

Ali was an icon for his career in the ring. But his refusal to renounce his principles, even amongst endless slander in the press and the loss of his livelihood, is an example to all. Principles matter. Character matters. It can be easy to go with the prevailing wind, but figures who have values that they’re willing to live and die by are rightly the most respected. It’s something businesses could do with remembering.

Bazball

Lesson #3: It’s about mentality

Bazball is the term given to the England cricket team’s style of play under head coach Brendon ‘Baz’ McCullum and captain Ben Stokes. It is defined by aggression and positivity. England teams under Bazball do not consider the draw. They play to win, even and especially when it means they risk losing.

A key aspect of Bazball revolves around relieving mental pressure –– rather than condemning players if they get out in a reckless way, they are praised all the same and given freedom to play as themselves. It is about instilling a mindset that as long as players are having fun and entertaining the crowd then they are doing their job. Get caught out on the boundary playing a big shot when you could have just blocked the ball? No worries, next time go even bigger.

It’s proved effective. In the 15-month span before McCullum’s appointment, England had played seventeen Tests, winning one, drawing five, and losing eleven. In the Stokes-McCullum era, they have played twenty-two Tests, winning fourteen, losing seven, and drawing one. England also score their runs significantly faster than any team in Test history.

Looking at those stats, one would think that some large overhaul of personnel must have taken place. But it has not. It is almost exactly the same players as before. The only difference is mentality. By prioritising positivity, aggression and freedom, and most of all by removing judgement and fear of failure, the self-same players are drastically outperforming old versions of themselves. Any business would do well to learn from this approach.

Pep Guardiola

Lesson #4 –– Have a vision, bring it to life

Pep Guardiola is one of the greatest football managers to ever live. Arguably the greatest. His Barcelona team of Messi and co. is widely considered the best to ever play the game. Meanwhile, his Manchester City team have won six out of the last seven Premier League titles and won the treble (Premier League, FA Cup, Champions League) in 2023. So, what can businesses learn from the Catalan?

Pep Guardiola is a control freak. That can be a negative in business, so it helps that he is also a genius. What marks him out, though, and makes him the most emulated manager of modern times, is that he has a vision of how he wants his teams to play and then does everything he can to bring that vision to life. Sometimes that means ruthlessly removing any cog –– no matter how effective has proven itself in the past –– that doesn’t meet his singular vision.

An obvious example would be the former England goalkeeper Joe Hart. When Pep Guardiola arrived at Manchester City, Hart was the keeper for his national team and had won back-to-back Premier League Golden Glove awards (the award for conceding the least goals in the league), having helped the team to two Premier League titles. That didn’t matter to Pep. He wanted a goalkeeper who was good with his feet and could be relied upon in possession. Hart was a mere shot-stopper. As such, he was ousted without ceremony or contrition. It was ruthless. But the subsequent success of City suggests it was the right call.

Guardiola plays a certain style of football that, like him, is based on control. His team dictates the flow of the game. It is not about individual brilliance, though of course that helps. Hart is just one example of a player ousted for not meeting his standards. Others have had to mould their game to his style in order to stay in favour. It’s a binary choice: play his way or don’t play. It sounds dictatorial but it is more team-oriented than that. Pep plays a system. If one player breaks out of that system to do his own thing, he leaves his teammates exposed. It is all carefully orchestrated so that all the distinct parts are working together to form a greater whole.

Herein lies the lesson. All companies have a structure. It’s important that all departments are working towards the same goal, that they are aligned and willing to do what’s best for the system to work rather than putting themselves or their department ahead of the team. Have a vision, stick to it. If you can see something doesn’t fit, remove it. It may be tough at the time, but it’s for the greater good.

Roger Federer

Lesson #5: Stay calm, make your opponent sweat

Roger Federer was the embodiment of grace. He moved balletically, floating across the court, and struck the ball with a rare poetic beauty. It was this inimitable style as much as his litany of Grand Slam titles that endeared him to the public, and brought tennis dizzying popular appeal.

The thing that amazed people most of all was his disposition. He didn’t shout, didn’t grimace, didn’t frown or moan; it seemed like he didn’t even sweat. He possessed a serenity that unsettled his opponents. On the occasions he was losing, which were rare in those early days, he seemed totally unphased by the score. Opponents hoping to rattle him ended up rattled themselves by their inability to breach his mental fortress. But it wasn’t always like that.

It’s no secret that a young Roger Federer was not simply less serene but an outright tantrum-merchant. One can see footage of his adolescent days online as he berates umpires and shatters rackets against the ground. No one thought this young hothead would go on to redefine the game he so loved.

Federer sought the help of a psychologist for his rage issues and one can only hope they were well compensated because they changed the trajectory of his career. A measured, unflappable disposition is easy to crave and hard to achieve. But entirely worthwhile if you can get it.

Any good leader will possess a level of calm and judgement. And just like you never realised quite how resilient Federer’s temperament was until he was losing, you can’t know the mental strength or fragility of your boss until things get tough. There are many things that make a good leader, but handling a bad day or difficult situation with grace and amenability is an important one. Both leaders and workers would do well to channel their inner Federer and not allow themselves to be phased by the situation around them. It doesn’t help you. It only helps those who wish you to lose. Don’t give them the satisfaction.

Lessons from sport

These are just five useful lessons but there are any number of other sports stars we could have included. For now though, if you want to succeed in business, make sure you’re willing to take some hits, have principles you’ll stick to, imbue yourself and those around you with a positive mentality, have a vision that you can help bring to life, and stay calm; if that young Swiss hothead could change his ways you can too.

Introduction

Founded by Jeff Bezos in 1995, Amazon has revolutionised the book market and significantly influenced the electronics and technology sectors. Bezos, recognised for his innovative leadership and named Fortune’s Businessperson of the Year (Gradinaru et al., 2020; Amazon, 2020), led Amazon through a substantial revenue surge during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite facing government scrutiny and workplace culture challenges, Bezos’s adaptive leadership style was pivotal (Gradinaru et al., 2020).

In 2021, Bezos transitioned from CEO to Executive Chair, marking a significant shift in Amazon’s leadership, with Andy Jassy taking over as CEO (Amazon, 2020). This article applies Transformational Leadership Theory, initially conceptualised by Burns and expanded by Bass, to explore Bezos’s leadership at Amazon. This analysis will consider the broader implications of his leadership in the tech and retail sectors (Burns, 1978; Bass, 1985; Botha et al., 2014; Gradinaru et al., 2020; Stewart, 2006).

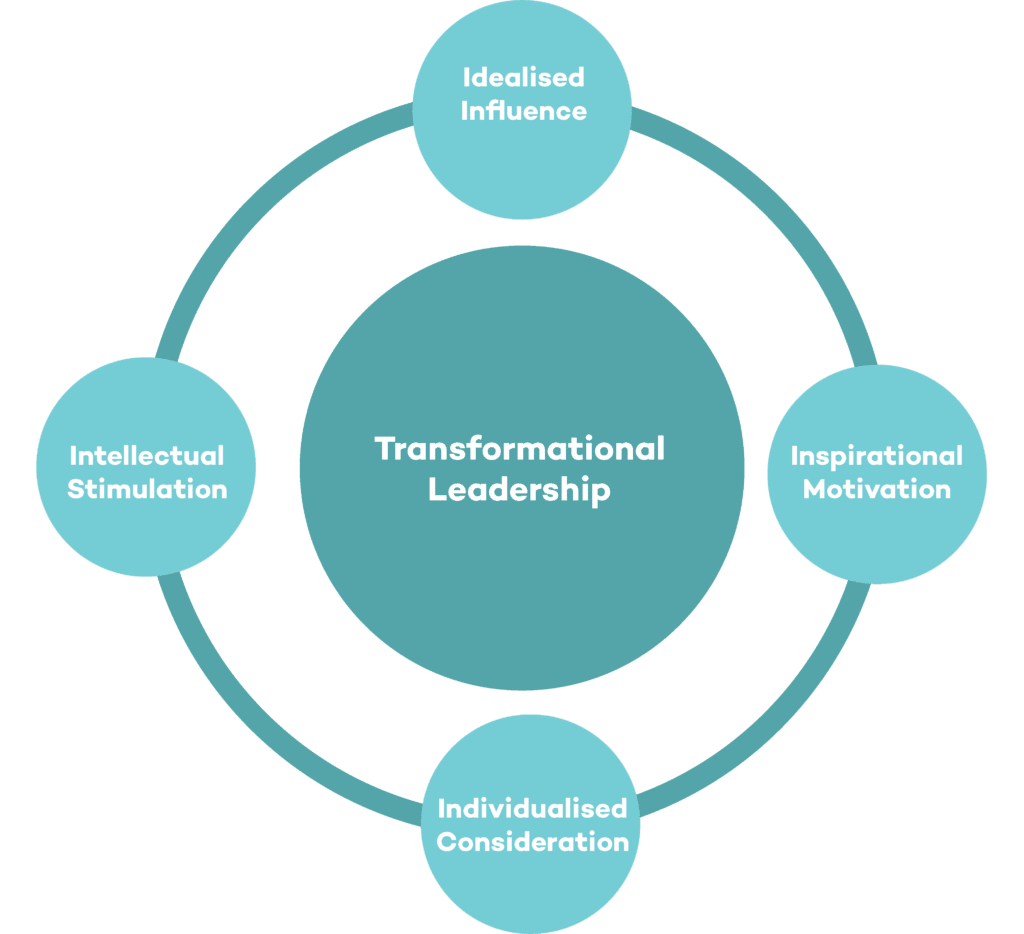

Transformational Leadership Theory and Jeff Bezos

Inspirational Motivation: Jeff Bezos’s tenure at Amazon is a testament to Inspirational Motivation, one of the pillars of Transformational Leadership Theory. His ability to cast a strategic vision has transformed Amazon from an emerging online bookstore into a global leader in e-commerce and cloud computing and redefined retail and technology industries. Bezos’s launch of Amazon Prime and the development of Amazon Web Services (AWS) serve as benchmarks of his capacity for long-term vision and strategic agility, which have been instrumental in rallying employees and stakeholders around a shared, ambitious goal (Densten, 2002; Stone, 2013; Denning, 2018).

Intellectual Stimulation: Under Bezos’s leadership, Amazon became a centre of innovative activity, embodying the Intellectual Stimulation component of Transformational Leadership. Bezos cultivated an environment ripe for critical thinking and creative problem-solving, leading to pioneering ventures such as Kindle, Echo, and the expansion into AI through Alexa. Amazon’s expansion into space exploration with Blue Origin underscores Bezos’s commitment to exploring and investing in new frontiers of technology and space (Peng et al., 2016; Rivet, 2017).

Individualised Consideration: The principle of Individualised Consideration reflects a leader’s attention to fostering the development and growth of their followers. Through Bezos’s implementation of leadership principles and the ‘Day 1’ philosophy, he aimed to empower employees to act as owners, fostering a culture of innovation at Amazon. However, balancing the drive for innovation with the well-being of employees at Amazon’s fulfilment centres has been challenging, evidenced by reports of demanding working conditions that raise questions about the application of this leadership component in practice (Khalil & Sahibzadah, 2021; Bal & Lub, 2015).

Idealised Influence: Bezos’s adherence to high ethical standards and relentless focus on customer satisfaction has solidified his status as a role model, displaying Idealised Influence. However, despite the customer-centric nature of Amazon’s mission, the company has faced criticism regarding its treatment of employees, suggesting a discrepancy between the values professed and those practised within different echelons of the organisation (Grădinaru et al., 2020; Enciso et al., 2017).

Critical Application to Bezos’s Leadership: While Bezos’s strategies at Amazon indicate transformational leadership, the tension between the company’s aspirational objectives and the operational realities of its workforce indicates a complex application of Individualised Consideration and Idealised Influence. Notably, the dichotomy between Amazon’s innovation-driven culture and its warehouse operations points to the potential oversights in aligning transformational leadership principles with the day-to-day experiences of all employees (Briken & Taylor, 2018).

Impact Analysis: Amazon’s remarkable growth trajectory under Bezos, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, is a clear indicator of the effectiveness of his transformational leadership approach. Nevertheless, the company’s agility and resilience during this period were occasionally marred by publicised accounts of its workplace practices, suggesting a need for a more balanced application of transformational leadership principles that consider the workforce’s well-being.

Comparative Insights: Bezos’s approach, marked by a relentless pursuit of customer satisfaction and a vision for the future, sets him apart from the distributed leadership models prevalent in smaller organisations, where shared decision-making and collective autonomy are more common (Solanki, 2019; Ghez, 2019; Cope et al., 2011).

Broader implications and critical evaluation

Bezos’s transformative leadership has undeniably established a new paradigm in business, demonstrating how a leader’s vision can lead to unprecedented success. However, the complexity and scale of Amazon have revealed that such a leadership approach may have limitations, particularly in ensuring ethical labour practices across all levels of the organisation. As Amazon continues to grow, the balance between innovation and the ethical treatment of employees remains a pivotal area for leadership attention.

In evaluating Jeff Bezos’s leadership through the lens of Transformational Leadership Theory, it is evident that while there is a strong alignment with the theory’s principles, the application in the context of Amazon’s operational realities has its challenges. The insights from Bezos’s leadership journey at Amazon offer valuable lessons for future leaders, emphasising the importance of balancing visionary goals with a commitment to ethical and responsible management.

Conclusion

Jeff Bezos’s leadership of Amazon showcases the transformative power of visionary leadership as outlined by Transformational Leadership Theory. His journey from creating a pioneering online bookstore to leading a tech empire exemplifies Inspirational Motivation and Intellectual Stimulation. However, the complexities of Individualised Consideration and Idealised Influence within Amazon’s expansive operations reveal the challenges of applying this theory in practice, particularly regarding employee well-being and workplace culture.

While Bezos’s approach has undoubtedly shaped Amazon’s success, it also highlights the necessity of balancing innovative ambitions with the responsibility of ethical leadership. The insights from Bezos’s leadership style offer valuable lessons for aspiring leaders, emphasising the need to adapt and evolve while remaining committed to ethical practices and employee empowerment.

In summary, Bezos’s legacy at Amazon aligns with the core tenets of Transformational Leadership Theory. However, it also underscores the importance of addressing the nuanced demands of leading a diverse and complex workforce. Future leaders can draw from this case study the importance of harmonising a clear vision with the conscientious treatment of employees to navigate the challenges of modern corporate leadership effectively.

References

Amazon. (2020). How we operate. Available at: https://www.aboutamazon.co.uk/uk-investment/our-principles-for-how-we-operate [Accessed 16 December 2023].

Bal, P. M., & Lub, X. D. (2015). Individualisation of work arrangements. In Current Issues in Work and Organisational Psychology. Psychology Press.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press.

Botha, A., Kourie, D., & Snyman, R. (2014). Coping with continuous change in the business environment: knowledge management and knowledge management technology. Chandos Publishing.

Briken, K., & Taylor, P. (2018). Fulfilling the ‘British way’: Beyond constrained choice—Amazon workers’ lived experiences of workfare. Industrial Relations Journal, 49(5-6), 438-458. https://doi.org/10.1111/irj.12230

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. Harper & Row.

Cope, J., Kempster, S., & Parry, K. (2011). Exploring distributed leadership in the small business context. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(3), 270-285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00307.x

Denning, S. (2018). The role of the C-suite in agile transformation: the case of Amazon. Strategy & Leadership, 46(6), 3-8. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-05-2018-0037

Densten, I. L. (2002). Clarifying inspirational motivation and its relationship to extra effort. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 23(1), 40-44. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730210414595

Eisenbach, R.J., Watson, K., & Pillai, R. (1999). Transformational leadership in the context of organisational change. Journal of Organisational Change Management, 12, 80-89.

Enciso, S., Milikin, C., & O’Rourke, J. S. (2017). Corporate culture and ethics: from words to actions. Journal of Business Strategy, 38, 69-79. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBS-11-2016-0142

Ghez, J., & Ghez, J. (2019). Case study: Strategizing at Amazon when globalisation comes under pressure. In Architects of Change: Designing Strategies for a Turbulent Business Environment (pp. 111-125).

Grădinaru, C., Toma, S.-G., Catană, Ș., & Andrișan, G. (2020). A view on transformational leadership: The case of Jeff Bezos. Manager Journal, 31, 93-100.

Khalil, D. S., & Sahibzadah, S. (2021). Leaders’ individualised consideration and employees’ job satisfaction. Journal of Business & Tourism, 7, 1-10.

Peng, A. C., Lin, H. E., Schaubroeck, J., McDonough, E. F., Hu, B., & Zhang, A. (2016). CEO intellectual stimulation and employee work meaningfulness: The moderating role of organisational context. Group & Organization Management, 41(2), 203-231. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601115617086

Rivet, D. J. (2017). Amazon’s superior innovation: A study of Amazon’s corporate structure, CEO, and reasons behind why it has become the most innovative company in today’s market.

Solanki, K. (2019). To what extent does Amazon.com, Inc success be accredited to its organisational culture and Jeff Bezos’s leadership style? Archives of Business Research, 7(11), 21-40. https://doi.org/10.14738/abr.711.6969

Stewart, J. (2006). Transformational Leadership: An Evolving Concept Examined through the Works of Burns, Bass, Avolio, and Leithwood. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy.

Stone, B. E. (2013). The everything store: Jeff Bezos and the age of Amazon. Little, Brown and Company.

Introduction

The EU’s Network and Information Systems Directive (NIS2) is scheduled to come into effect across member states on October 18th, 2024. Businesses that fail to put the right measures in place by that date are at risk of facing serious regulatory problems, including the potential suspension of C-suite executives and fines of up to €10 million.

A worrying number of businesses in Ireland are either unaware of NIS2 or ill-prepared for its implementation. Companies wishing to comply with the directive need to be aware of the many updates they must make to their business before the rapidly approaching deadline. This article will explain what NIS2 is, who it affects, why it’s important, and what companies can do to prepare themselves for its enforcement.

What is NIS2?

The NIS2 Directive is the EU-wide legislation on cybersecurity. It’s focused on enhancing cybersecurity and boosting digital resilience across Europe. It could impact more than 180,000 organisations across member states including 4,000 in Ireland, from sole traders through to large-scale enterprises, in industries from finance to transportation to healthcare. [1]

In March, Microsoft Ireland’s national technology officer, Kieran McCorry, summarised NIS2’s key requirements in Tech Central, writing: “A key feature of NIS2 is the requirement to implement a benchmark of minimum cybersecurity measures including risk assessments, policies and procedures for cryptography, security procedures for employees with access to sensitive data, multi-factor authentication, and cyber security training.” [2]

He goes on, “The legislation also includes an emphasis on the need for cyber security in supply chains and prioritises the relationship between companies and direct suppliers. Additionally, NIS2 aims to harmonise cybersecurity requirements and enforcement across EU member states, while directing companies to create a plan for handling security incidents and managing business operations during and after a security incident.”

What that means in practice is that companies will be required to address risk management through the implementation of basic cyber hygiene procedures and cybersecurity training, regular software updates, access restrictions, encryption technologies, and monitoring of IT systems [3]. Risk management differs from company to company, depending on size and industry, but most companies will have to implement some version of those policies, if not more.

Affected companies will also have to register with national authorities. By recording and monitoring relevant companies, the EU is hoping to improve safety standards and cooperation in the event of safety incidents. Companies will be required to report significant security incidents to the authorities without delay, providing the nature of the incident, its impact, and the countermeasures taken. In some cases, information obligations to customers also exist. [4]

Companies classified as “particularly important companies” will have to provide evidence that they have implemented these required safety measures or face sanctions.

Speaking to the Irish Examiner, Neil Redmond, director of risk and regulation at PwC Ireland, explained how companies can figure out their classification status.

“Entities are classified as either ‘essential’ or ‘important’ based on their size, the sector they operate in and their importance to the public interest,” he says. “Large and Medium enterprises may be considered ‘essential entities’. These are organisations in sectors of high criticality with in excess of 250 employees and in excess €50m in annual revenue.” [5]

“Some of the ‘essential entities’ covered by NIS2 include those in sectors like energy, transport, health, banking and public administration while ‘important entities’ include waste management as a principle economic activity and postal services among others,” he adds.

What happens if you don’t act?

Ireland’s national competent authority for public sector bodies, the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), will have the remit to impose more stringent penalties for non-compliance under NIS2. [6]

For those entities deemed “essential”, the maximum fine is €10 million or 2% of global annual revenue, whichever is higher. This is reduced slightly for “important” entities but remains significant at €7 million of 1.4% of global annual revenue.

NIS2 introduces a momentous shift in cybersecurity accountability. Security teams will no longer be held solely responsible for non-compliance. Instead, management and executives can be found personally liable if gross negligence is found following a cybersecurity incident. Chief executives may be suspended from their duties over a significant breach.

That’s not to mention the reputational damage companies can suffer if they are found to not be complying with the new regulations. It can result in a loss in investor and customer confidence, most especially if a C-suite figure ends up being suspended.

Why is it important?

According to Microsoft’s ‘Cybersecurity Trends in Ireland 2023’ report, more than 70% of leaders were either unaware or unprepared for compliance with NIS2. Of those who were aware of NIS2, 20% felt they were currently compliant with the legislation and 20% believed they were not compliant. While 60% of all respondents were unsure if they are or not. Positively, 31% of organisations were planning to invest in their strategy to achieve compliance with NIS2 and 29% had a roadmap in place to achieve this. [7]

The need for increased cybersecurity is pronounced. According to the same report, 46% of respondents had faced cyber incidents in the last three years, with 30% experiencing data breaches. Only 14% reported incidents to regulatory bodies, 44% performed risk assessments and 38% employed a multi-layered defence strategy. As already noted, these will all be requirements from October.

Ireland is no stranger to cybersecurity attacks. The HSE attack of 2021 lives long in the memory. It remains the largest known attack against a health service computer system in history. Fears linger over future attacks on a similar scale.

PwC’s recent Irish CEO survey revealed that 90% of Irish business leaders are concerned about their organisation’s exposure to cyber risks. Meanwhile, their Digital Trust survey revealed that 53% of Irish business leaders expect GenAI to lead to catastrophic cyber attacks in the year ahead [8]. The NIS2 directive is nothing if not timely.

What can companies do to prepare?

Writing in the Irish Times, Carol Murphy, an EY partner and head of technology risk, suggests companies start by assessing if and how NIS2 will impact them [9]. They should work out their designation then work to understand what additional demands the new directive is expecting them to implement.

She advises leaders that they “need to understand that this is not purely a cyber, technical, or regulatory issue to be solved – it is a mandatory enterprise imperative that will demand appropriate governance and resourcing from the highest levels.” Given higher-ups will be held accountable for failure, it especially behoves them to make sure the entire organisation is aware of what is expected of them.

PwC advises five key actions companies can take now to ensure they are in compliance when October rolls around. They are (1) Understand your business’s regulatory landscape (2) Assess your ability to comply (3) Proactively test incident response processes (4) Embed resilience testing (5) Develop an end-to-end threat and vulnerability management programme. [10]

We’ve addressed the first in Murphy’s suggestions. In terms of assessing ability to comply, PwC recommends adopting a cybersecurity controls framework. “Mapping specific controls in operation within your business to each NIS2 clause can help inform you of areas where the organisation cannot meet its NIS2 obligations at present.”

In order to proactively test incident response processes, they suggest using tabletop exercises and comprehensive crisis simulation activities. They also suggest, given the importance of reporting incidents to NIS2’s directive, that companies actively test their ability to communicate effectively internally and externally during and following an incident.

Regarding the embedding of resilience testing, they suggest regular testing with a risk-based approach to scope and frequency. “Organisations should define recovery time objectives (RTOs) and recovery point objectives (RPOs) for their critical systems to set the minimum expectations of the business for recovering its key digital services.”

In terms of developing an end-to-end threat and vulnerability management programme, they suggest exercises such as vulnerability scanning by manual penetration tests conducted by experienced cybersecurity professionals on key systems. They note that vulnerability testing should cover all areas relevant to cybersecurity, not just traditional IT systems. They suggest communicating the volume and criticality of open vulnerabilities within the business “to help instil cultural awareness and accountability for the organisation’s security.”

NIS2: What companies need to know

The new NIS2 directive will come into effect in October, with a number of Irish businesses still unprepared for its implementation. The directive will enhance cybersecurity and boost digital resilience across Europe. This is especially important given the growing prevalence of cyber attacks across the world, not to mention the extent to which such attacks could worsen as AI develops. Not preparing can result in major fines or even suspensions for executives.

To avoid such outcomes, businesses need to prepare now. That starts with finding out your designation, assessing your ability to comply, testing your incident response processes, embedding resilience testing, and developing threat and vulnerability management programmes. It’s down to leaders to make cybersecurity part of their company culture. Leaders that fail to do so will soon be held accountable.

More on Cybersecurity

Combatting Cybersecurity Risks

The Unsolvable Problem of AI Safety

Sources

[3] https://www.cocus.com/en/nis2-security-requirements-for-companies/

[4] https://www.cocus.com/en/nis2-security-requirements-for-companies/

[5] https://www.irishexaminer.com/business/technology/arid-41372734.html

[6] https://www.pwc.ie/services/consulting/insights/understanding-nis2-directive.html

[8] https://www.irishexaminer.com/business/technology/arid-41372734.html

[10] https://www.pwc.ie/services/consulting/insights/understanding-nis2-directive.html

Introduction

Research has shown that partaking in creative outlets creates stronger social relationships, reduces stress, and allows us to develop a deeper appreciation for the world around us [1]. It also helps boost confidence, foster innovation and develop extended social networks [2]. Not to mention improving mental health, reducing anxiety and helping to combat dementia [3].

But don’t just take our word for it. Gavin Clayton, executive director of the leading mental health and arts charity Arts and Minds, conducted research over a seven-year period in which participants experiencing stress, depression, and anxiety partook in activities such as sculpture, oil painting, and printmaking. The study found a 71% decrease in feelings of anxiety and a 73% fall in depression. Around 76% of participants said their well-being increased and 69% felt more socially included [4].

A similar study at Drexel University found that 75% of participants experienced lower cortisol levels, a marker of stress, after engaging in 45 minutes of art-making [5]. Other research has found that writing helps people manage their negative emotions in a productive way, and painting or drawing helps people express trauma or experiences that they find too difficult to put into words [6].

The healing power of art

Shereen Bar-or Becerra, Creative Arts Therapist and Founder of Art Therapy Collective in New York, says that “if variety is the spice of life, creativity is the seasoning…When we practise self expression through nonverbal means, we are able to organise and process difficult emotions and increase our capacity for frustration tolerance while inherently improving our quality of life and capacity for joy.” [7]

“The arts can bring a feeling of playfulness to places you’d not expect to find them,” says Nils Fietje, of the WHO’s regional office in Copenhagen [8]. As such, art is often used as a way of healing. Fietje was specifically speaking about the role of clown doctors when making the above statement. These doctors are from Red Noses International, working at emergency accommodation centres in Moldova following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In a similar vein Rachel Clarke-Hughes, head of engagement at the Playhouse Theatre in Derry City, works with victims and survivors of The Troubles so that they can share their personal testimonies on stage with live audiences. “It’s about truth, healing and reconciliation through arts and storytelling,” she said, speaking to the Irish Times. [9]

Wounded civilians displaced by war and survivors of intense national trauma are extreme examples of art being used to heal. But it can and does also help fix more day-to-day struggles.

Art vs workaholism

Productivity culture is at a fever pitch. We must all have a primary and side-hustle. We must be seizing the day, getting up at 5am, being the hardest worker in the room, doling out high-octane productivity mantras on LinkedIn and consuming them back triple-fold. We must work ourselves into the ground until we’re so burned out that we’re not useful to anyone, least of all ourselves.

Or, we could treat our minds and bodies with a little respect and find some balance.

“Workaholic culture insists that being successful means making big sacrifices outside of work, even at the expense of personal health, but I’ve come to believe that it’s not all or nothing,” says Kenny Mendes, Head of People and Operations at Coda, speaking to Forbes. “I urge younger workers to think about sustainable high performance over a long career — it’s a marathon, not a sprint.” [10]

Mendes sees creative outlets outside of work as pivotal to that longevity. He says that not only will it be a stress release, offering all the aforementioned benefits, but it will improve your at-work performance as well. “Finding an outlet that helps clear your mind and gets you into a different state of flow leads to better performance during your 9–5,” he says. [11]

Keeping art separate

Despite Mendes’ insistence that an outside hobby makes a positive impact on work performance, others insist it’s important to keep your creative outlet entirely separate from your working day-to-day. It’s not an additional side-hustle, it’s not a self-improvement tool –– quite the opposite, it’s a way to detach and unwind.

“For me, I like to think of leisure in its purest sense — that is, it is time away from work, not facilitating it,” said Thomas Fletcher, chairman of Leisure Studies Association and a senior lecturer at Leeds Beckett University. “Is a hobby actually leisure if we are making money from it?” [12]

Fletcher argues that in viewing our hobbies as something that can add richness to our work, we have got things entirely inside out. We should instead be using our work as a way to add more value to our life. “In thinking about the relationship between work and leisure,” he said, “I would argue that rather than thinking about how leisure can promote greater productivity at work, a more important consideration is about how work inhibits our leisure time.” [13]

Art for women

Eve Rodsky, author of Find Your Unicorn Space: Reclaim Your Creative Life in a Too-Busy World, argues that women, in particular, are in need of space to pursue a creative outlet.

“The expectations on women, especially after they have children, are that we will be happy and fulfilled by staying within three boxes,” she says. “(1) We’re allowed to be parents of children. (2) We’re allowed to be partners. (3) We’re allowed to make money because we have to help our household. If you want to be an acrobat, if you want to be a baker, if you want to be a mountain climber, or if you want to pursue anything for yourself, society will shame you back into one of those three boxes.” [14]

Rodsky argues that society has come to view men’s time as significantly more valuable than women’s time. “Society views men’s time as if it’s finite like diamonds, and it views and treats women’s time as if it’s infinite like sand,” she says. “And when you have that type of discrepancy it leads to internalised guilt and shame for our own time choice.” [15]

She cites the fact that even in our supposedly equal society, school nurses will always call the mother parent over the father to come collect their sick child from school. The mother’s day can be put on pause. The father’s time should not be interrupted.

Rodsky says creative time or unicorn space offers women sanctuary from the world of deadlines, expectations and other people’s demands, while also serving as inspiration for other aspects of life. It is “not just a hobby,” writes Elizabeth Pearson, profiling Rodsky in Forbes, “it’s an essential element of a woman’s life, supporting both [their] career and personal well-being.” [16]

Getting started

For those unsure how to get started in their creative outlet, Wendy Raquel Robinson, an Emmy Award-winning producer, philanthropist and actress, suggests starting with classes. “Even if it’s just online, if you’re not ready to dive into a class, you can join or even just watch a class online. Even just watching a YouTube video on how to do something to pique your interest. Start with watching, learning, taking notes, and getting a good feel for it.” [17]

Robinson also advocates journaling. “Start with writing your thoughts out every day. It’s cathartic and also, when you look back and see the growth from month to month, it’s powerful.”

Meanwhile, Bar-or Becerra says, “The best way to begin anything is to follow your feet –– lean into what makes you feel present. Self-awareness is required for active engagement so begin by noticing the moments that bring you joy or grounding. Being creative and intuitive can be as simple as learning how to create cohesion and connection with your internal and external world.” [18]

What can leaders do?

In a survey conducted by the World Economic Forum, 90% of business leaders highlighted the importance of creativity in remaining competitive [19]. As such, it behoves managers to do everything in their power to support their staff’s creative endeavours, inside the office and out.

It may seem like it’s not the manager’s place to intervene in creative matters. Speaking at a two-day colloquium at Harvard Business School, Intuit co-founder Scott Cook wondered whether management was “a net positive or a net negative” for creativity. “If there is a bottleneck in organisational creativity,” he asked, “might it be at the top of the bottle?” [20]

During the conference, leaders came to a useful realisation: One doesn’t manage creativity. One manages for creativity.

Cook told the story of an eye-opening analysis of innovations at Google: Its founders tracked the progress of ideas that they had backed versus ideas that had been executed in the ranks without support from above, and discovered a higher success rate in the latter category. Companies need to break past the “lone inventor myth” in which they’re reliant on one supposedly genius founder to innovate alone. It’s an unsustainable model.

Other suggested creativity hacks are to not allow any bureaucracy into the initial creative stages –– let creatives work freely before deciding whether or not an idea is possible. Putting a ceiling on things too early can restrict creativity. Also, leaders should make their teams diverse –– in race, gender, age and thought. Having a wide range of viewpoints helps creativity grow.

Leaders can also make sure they support staff in their creative endeavours outside the office. Ray Corral, founder of Mosaicist in Coral Gables, offers grants and space to his workers to help develop their own individual pursuits. On top of that, each year his whole team gets together to create something new unrelated to the work they do. “This annual tradition fosters personal growth and satisfaction and injects a fresh, innovative spirit into our workplace,” he says. [21]

Why you need a creative outlet

Creative outlets offer an endless list of benefits: improved mental health, less stress, greater productivity, inspiration, a way to unwind and disconnect, a way to forge new communities, and a way to combat workaholism. Its benefits can be especially helpful for women, who need time to pursue their passions free from societal pressure to adhere to some reductive norm. Classes and journaling can be a great way to start, but the truth is only you know exactly what it is you want to pursue –– follow that urge. And if you’re a manager, do everything you can to support creative outlets in your team. A workforce that is happy and creative benefits everyone.

More On Burnout

The Million-Dollar Impact of Burnout & Busyness Culture

More On Creativity

Walking, and the benefits of everyday creativity

The value of creativity with Pat Stephenson – Podcast

From Creative Visionary to World-Renowned Artist: The Inspiring Journey of Paul Hughes – Podcast

Sources

[1] https://www.mciinstitute.edu.au/wellbeing/creative-outlets

[3] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16439826

[4] https://www.mciinstitute.edu.au/wellbeing/creative-outlets

[5] https://drexel.edu/news/archive/2016/june/art_hormone_levels_lower

[6] https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/320947.php

[12] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/10/smarter-living/the-case-for-hobbies-ideas.html

[13] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/10/smarter-living/the-case-for-hobbies-ideas.html

[19] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/04/5-things-you-need-to-know-about-creativity/

[20] https://hbr.org/2008/10/creativity-and-the-role-of-the-leader

Introduction

The latest survey by GOBankingRates, involving over 1,000 US adults, revealed that 57.65% are considering a career shift in the coming year [1]. Meanwhile City & Guilds Group research revealed a third of British people want to change their job. [2]

This desire for change is in part generational, with the same GOBankingRates poll finding that 83% of Gen Z consider themselves to be “job hoppers” [3]. But as Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, a professor of business psychology at University College London and Columbia University, writes in Harvard Business Review: “Contrary to what people think, career pivots are far less dependent on age than on other, organisational, psychological, and contextual factors. In other words, there is no such thing as the “ideal age” for a change; instead, other factors should be considered.” [4]

According to the US Department of Labor, the average person will change careers 5-7 times during their working life. Approximately 30% of the total workforce will change jobs every 12 months. [5].

So, what is the best approach to handling a career pivot? This article will help explain how you should decide whether you want to change careers, what might drive that change, and offer advice for how to best position yourself to transition smoothly.

Why change?

Herminia Ibarra of the London Business School divides the causes for change into two key categories: Situational drivers and personal drivers. [6]

Situational drivers, which also can be thought of as external drivers, are market forces such as the economy, the state of your industry, a restructuring in your company or emerging opportunities elsewhere. An example might be people who sense that AI will soon nullify the need for their existing job. As such, they are choosing to pivot careers now in order to not become collateral damage later.

Personal drivers, which can also be thought of as internal drivers, involve your personal experiences and preferences or network. An example might be people who chose to transition during the pandemic. While the pandemic was obviously an external event, for a lot of people it served as a wake-up call and inspired them to start pursuing a path that better aligned with their skills and passions.

Whatever your reason for pivoting, it’s first worth considering whether doing so is the right move.

Should you pivot?

Before pivoting, you should ensure that you’re certain it’s what you want to do. In Harvard Business Review, Dorie Clark, a marketing strategist who teaches at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business, suggests some easy ways to do that. [7]

First, you could transfer internally or reinvent your existing job. Turnover has been found to cost the employer up to 2x the employee’s annual salary and the number of resignations spiked in 2021 to a record 47 million voluntary departures. As such, companies are increasingly desperate to retain their talent. Before quitting for good, why not explore an internal transfer? Perhaps that will be sufficient to sate your desire for something new.

Second, be sure to validate your interests before doing anything drastic. Clark writes of a woman who always dreamed of quitting her job to become a florist. Except after spending a day shadowing a florist, she discovered that a large part of the job consisted of working in cold temperatures, which was a no-go for her. Oftentimes our grass-is-always-greener mentality means we’re assessing our idea of a job not its reality. Before pivoting, be sure to do your homework so you have a full picture of your day-to-day requirements.

Third, speak to those close to you. Your loved ones want what’s best for you. Obviously you would hope they support you, but they may be able to offer some third-party perspective that you are missing. If they raise doubts, think about those doubts and come up with a response that either nullifies them or shows that you have at least considered them, even if you’re willing to take a risk all the same.

The final suggestion Clark makes is to “stretch your time horizon.” In practice, that means asking yourself whether your pivot requires you to quit your job right away. If you’re going to another industry, perhaps you would be better placed if you dedicated a certain amount of time to bolstering your skills in that new industry around your current work first. You could undertake an evening or weekend course, network, or study on your own time. That way you won’t take a financial hit but can still move on when you’re good and ready. If doing so, be sure to make a schedule for your new learning that you can stick to, be it two hours twice a week, all day Saturday, whatever. Without a rigidly adhered to schedule, it could recede into just another dream.

Professional identities

We’ve already mentioned Herminia Ibarra’s notion of personal drivers. Chamorro-Premuzic expands on that idea. To him, these pivots all boil down to our ‘professional identity’.

“Our identity is influenced not just by our past work experiences,” he writes, “but also by our projected ones. When we feel that we are headed in a direction that is not congruent with our self-concept, such that our perceived “actual self” is out of sync with our “ideal self,” we are motivated to take action and change.” [8]

We can offer practical advice for how to handle a pivot but realistically whether you should or not comes down to your own intuition, that feeling in your gut. Most of us have experienced it at some point or other, be it in work or a personal relationship. If you’re feeling deep down that you’re on the wrong path, it probably is time for a change.

A shift in mindset

Writing in the Financial Times, Elizabeth Uviebinene, author of The Reset: Ideas to Change How We Work and Live, writes of her pivot from a banker to a writer and brand strategist. She says the secret to a successful pivot is to adopt a student mindset and let go of ego.

Adopting a student mindset makes your pivot more exciting and less daunting. Uviebinene found that “starting from a place of, “what do you want to learn?”, allows you to consider opportunities you may not have thought of, in fields that do not immediately translate as a good fit.” [9] Maintaining that approach allows her to keep learning and growing rather than acting as if there is some grand end destination.

Making the pivot

Once you’ve decided that a pivot is what you want, there are a number of tips that can help you get ahead.

Elizabeth Grace Saunders, a time-management coach and author of How to Invest Your Time Like Money, advocates four key principles: (1) Accept the time commitment (2) Pick your focus (3) Layer in learning (4) Designate time. [10]

Accepting the time commitment is the start. Making a successful pivot will require sacrifices. You may see less of your friends and family, or lose your weekends. If you’re constantly battling the urge to maintain the life structure you had before with your new ambitions, you will find the process frustrating. It’s better to accept that, at least for a time, things will be different.

Once you’ve made the commitment, pick your focus. Research what is required to thrive in your new field. Do you need to go back to school or complete a certification course? If so, focus on that. Perhaps you can self-teach the necessary basics. If so, do that. If networking is key, put the time into finding out who could help you and reaching out, as well as finding networking events you can attend.

Layering in learning is the process of transforming activities you already undertake into opportunities for growth. If you always listen to a podcast on your hour-long commute, listen to a podcast or audiobook that is related to your new field.

Designating time is key. It’s also vital to ensuring the first step works. You don’t want your whole life to become a sacrificial act, never seeing friends, becoming isolated from your family. Designating time both helps ensure you have structure for learning and that you have a life outside of it. It could be two hours after work twice a week, or four hours on weekends; the specifics will depend on your requirements. But try to make sure it’s the same every week so that it becomes habit. That way you won’t feel guilty when you’re seeing friends or family outside of those structured hours.

Writing in Forbes, Cheryl Robinson, author of The Happy Habits Club, also suggests crafting a narrative for your pivot [11]. You will have transferable skills from whatever previous roles you’ve filled. And if you’re undertaking the steps above then you’re also on a path to developing the necessary new ones. But potential employers will want to know why they should choose you over someone whose experience already lies in this field. By crafting a narrative about your move –– why it matters to you, why this area is your passion –– you can help alleviate any doubts that this is just an impulsive decision. Your CV and Cover Letters are a great place to push this narrative.

Courses in Ireland

Ireland offers a number of adult learning services that can help workers make a transition. The Irish Times notes that, “Within the State sector, education and training boards (ETBs) have a dedicated adult education guidance service staffed by guidance counsellors and information officers, who offer support to those with the greatest need as well as those seeking support to change career direction.” [12]

The etbi.ie website provides a link to all adult guidance services offered throughout ETBs nationwide.

Meanwhile, last June, Taoiseach Simon Harris, then Minister for Further and Higher Education, launched more than 11,000 free or subsidised places on college courses “aimed at those who may have taken a degree in a specific discipline but who wish to change direction within their general area of expertise to one with very good employment potential.” [13] The government funds 90% of the course fee. The other 10% is paid by the participants.

How to approach a career pivot

Whether it’s down to situational drivers or personal drivers, career shifts are becoming increasingly normal. The advent of AI will no doubt create further need in the coming years, while the attitude of Gen Z and younger millennials suggest the trend is likely to continue.

Once you’ve decided that a career pivot is right for you, it’s time to adopt a shift in mindset. It may be difficult to return to a student attitude, especially for those who have already had a successful career in another field. But a desire to keep learning is necessary to maintain excitement about the switch and alleviate some of the more daunting aspects. It also allows one to continuously grow rather than getting complacent or stagnant.

A successful pivot comes from accepting the time commitment, picking your focus, layering in learning to your existing activities, and designating time so you have a solid schedule and can maintain a work-life balance. It can feel scary to start again. But the likelihood is you already know deep down whether it’s something you want to do.

More on Change

What is the “Fresh Start Effect” and how can we use it to our Advantage?

Sources

[1] https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/over-half-of-americans-are-planning-for-major-job-changes-in-2024

[2] https://www.ft.com/content/76800ee9-6442-4c18-9615-68ac4ac41b61

[3] https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/over-half-of-americans-are-planning-for-major-job-changes-in-2024

[4] https://hbr.org/2023/08/what-to-ask-yourself-before-a-career-pivot

[6] https://flora.insead.edu/fichiersti_wp/inseadwp2004/2004-97.pdf

[7] https://hbr.org/2023/02/how-to-make-a-career-pivot-without-taking-a-pay-cut

[8] https://hbr.org/2023/08/what-to-ask-yourself-before-a-career-pivot

[9] https://www.ft.com/content/76800ee9-6442-4c18-9615-68ac4ac41b61

Introduction

Loyalty is not what it was. As with everything in the modern world, the pace has upped and the foundations have grown a little shaky. It’s less and less common for someone to stay at the same company all their life. The expectations of employees have changed and the expectations of companies too.

So, what does workplace loyalty look like in 2024? This article will assess the benefits of loyalty, how it has changed with differing generational ideals, the downsides of having too much, and how to garner it in an increasingly transactional world.

The benefits of being loyal

Management experts say staff who are loyal to their employer are inclined to invest more time and effort in their jobs [1]. Unsurprisingly, this increased engagement tends to lead to better performance, which in turn makes loyal workers more likely to gain promotions and higher pay. Being loyal to an employer is also found to reduce job-related stress [2]. Loyal employees feel like they belong at their company and are more likely to actually fulfill that standardised CV promise of ‘going the extra mile’.

The downside of being loyal

While loyalty is of course generally a good thing, it can go too far. Overly loyal employers can be liable to commit unethical acts to either prove their loyalty or as a result of it. Equally, overly loyal employees can be taken advantage of by employers.

In terms of the former, examples are rife. At the Toshiba headquarters in Japan, leaders led employees to believe that they would receive a near lifetime appointment if they demonstrated commitment to the organisation, its goals, and its people. The carefully cultivated loyalty of staff allowed senior managers to get away with an accounting scandal for a prolonged period of time. Employees knew about the scandal but didn’t speak out. In the west, the Enron debacle is another obvious example.

Research backs up the theory that too much loyalty can lead to ethical breaches. A study conducted by the University of California, Berkeley and Harvard Business School found that “loyal” fraternity students were less likely to cheat on a puzzle-solving task than their less loyal counterparts. That is, until they were told the task was competitive, with the importance of beating rival houses to win a cash prize stressed. Suddenly, the loyal students became far more likely to cheat than their less loyal counterparts, even without being explicitly told to break the rules. [3]

Research published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology has found that the more loyal an employee is, the more likely they are to be targeted for exploitative practices by their manager. Employers expect a level of self-sacrifice from these employees. They feel comfortable asking them to work late or while on holiday, or to undertake tasks unrelated to their job duties without extra reward or pay.

“Employers take advantage of loyal and passionate workers because they believe that for [them], the work itself is its own reward,” says Neil Lewis, an associate professor of communication and social behaviour at Cornell University and author of a 2021 paper that also found employers likely to exploit overly loyal employees. [4]

“It’s a double-edged sword: loyalty has benefits for both employees and firms, but it can also keep us from seeing and doing things that need to change…It is useful to periodically step back and reflect on why we are loyal to particular people, things, or ideas.”

The changing landscape

Bruce Tulgan, author of It’s Okay to Be the Boss and The Art of Being Indispensable at Work, writes in Forbes that “loyalty isn’t dead –– it’s just changing” [5]. He notes that with the rapid-pace changes brought by globalisation and drastic technological advancements, younger generations have grown up in a state of flux.

“Gen Zers are comfortable in this rapidly changing web of variables,” he writes. “Uncertainty is their natural habitat: they’ve never known the world any other way.”

The pandemic obviously exacerbated the sense of instability for a number of young workers. The data for their yearning for meaningful work was borne out in the Great Resignation and Quiet Quitting phenomena. Unlike workers of old, millennials and Gen Z do not hand over their loyalty to their employers unquestioningly because they’ve come to see that they are unlikely to receive it in return.

Gallup’s latest state of the workplace report showed that half of the 122,416 employees who took part in a global survey were looking out for new work [6]. Amongst global turbulence and a side-hustle culture, it’s hardly surprising that workers are unwilling to put all their eggs in one basket. “No job is risk-free today, so it’s imperative you are intentional about how you actively manage that risk,” says Christina Wallace, senior lecturer at Harvard Business School and author of The Portfolio Life. [7]

Tulgan points out the misdiagnosis often given to younger employees by their older cohorts. “For a lot of leaders and managers, the takeaway is that young people today are less loyal. But loyalty shouldn’t be confused with blind obedience. Instead, they offer the kind of loyalty you get in a free market –– that is, transactional loyalty. This is the same kind of loyalty you extend to your customers and clients.” [8]

Amidst the understanding that their careers are going to have to be more dynamic than the generations that came before, younger workers want something in exchange for their loyalty. “Gen Zers are not about to do tasks outside the scope of their position in exchange for vague, long-term promises of rewards that vest in the deep distant future,” Tulgan continues. Mainly because they’ve seen all their adult lives that the long-term doesn’t exist anymore; the future is far too fragile to put their faith in.

As attitudes of workers have changed, the attitudes of those hiring have too. As such, showing loyalty by staying in a job for a long time can actually be seen as a negative.

“If you’ve only been in one industry, in one business, it can make you a little bit one-dimensional,” says Jamie McLaughlin, CEO of New York-based recruiting company Monday Talent in an interview with the BBC. “You might look at that [longevity] and go, how motivated is this person? Why haven’t they wanted to move? It can signal that professional development has stalled, or that workers have a smaller network.” [9]

Christina Wallace agrees. “I do think staying at a company too long is risky,” she says. “You start getting comfortable. Maybe you slow down on networking or stop looking at what your market rate might be elsewhere. You don’t keep up with how job descriptions in your industry are changing and whether you’re doing what you can to stay current.” [10]

With young people criticised for moving too much and overly loyal employees being exploited and thought to lack ambition, the modern climate can feel like a lose-lose. But work trends expert Samantha Ettus suggests there is a happy medium. “These days company loyalty is a rarity, so when I see someone who has stayed at their previous company for three-plus years, it’s meaningful,” she says. [11]

Though she also warns against staying much longer. “If you are at a company for more than seven years, it flags a potential lack of ambition,” she says.

Cultivating loyalty

Employees may be uncertain as to how loyal they should be to their company given the ever-changing landscape and the potential drawbacks of over-investing themselves. But employers will always want loyal employees. As noted earlier, it leads to better performance and creates a better atmosphere. So how can employers work to earn loyalty from their staff?

Obvious answers are promotions and pay rises. But these are not always possible and, let’s face it, most of the time businesses would rather avoid doling out more cash if they can help it. Thankfully there are other techniques too.

Writing in Harvard Business Review, Stephen Trzeciak, chief of medicine at Cooper University Health Care, Anthony Mazzarelli, co-president/CEO of Cooper University Health Care, and Emma Seppälä, a faculty member at the Yale School of Management, argue that the key consideration must be compassion. They define compassion as empathy plus action.

“Contrary to what many employers currently believe, the recent wave of employee attrition has less to do with economics and more to do with relationships (or lack thereof),” they write. “The data support that employees’ decisions to stay in a job largely come from a sense of belonging, feeling valued by their leaders, and having caring and trusting colleagues. Conversely, employees are more likely to quit when their work relationships are merely transactional.” [12]

They note that neuroimaging research shows people’s brains respond more positively to leaders who show compassion, while a compassionate culture has been linked with lower employee emotional exhaustion and less absenteeism.

They provide a slew of evidence-based advice as to how to be a compassionate leader, broken down below:

- To start small: A Johns Hopkins study found that giving just 40 seconds of compassion can lower another person’s anxiety in a measurable way.

- To be thankful: Meta-analytic research shows that gratitude makes us more others-focused and motivates us to serve others.

- To be purposeful: When you see an employee is struggling, instead of asking yes or no questions like “Do you need help?”, ask “What can I do to be helpful to you today?” or “What can I take off your plate today?”

- To find common ground: When we focus our empathy on just “our people”, it can reduce our compassionate behaviour on balance overall. Try expanding your empathy and compassion further afield.

- See it: When an employee goes “above and beyond” to help someone else, let people know.

- Elevate: Elevation is the positive state we experience after witnessing another person’s compassion, moral excellence, or heroism. Research shows both compassion and rudeness are contagious.

- Know your power: Imagine if compassion was your superpower. What possibilities would that open up in your career and life?

Workplace loyalty in 2024

Loyalty in the workplace has changed. Workers are unlikely to stay at one company all their lives and are perhaps ill-advised to do so. Doing so might lead their company to exploit them or cause other potential employers to perceive them as unambitious. Equally, barring rare exceptions, workers cannot expect their workplace to show unwavering dedication to them.

A lot of people blame young workers for their lack of loyalty, but it’s simply that their loyalty is different. Having grown up with and become accustomed to instability, a transactional form of loyalty suits them better. It helps ensure they’re not putting all their eggs in one wobbly basket. For employers looking to foster loyalty in their staff, pay rises and promotions are the obvious answer. But compassion must also play a role. We are all human at the end of the day. Sometimes all we need is to be seen and treated as such.

More on Employee Retention

Employee Retention: the Hows and Whys

Creating and fostering cultures of meaning

The Role of Empathy in the Workplace: Impact and Implications

Sources

[1] https://iaap-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1464-0597.00020

[2] https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0021-9010.78.4.552

[3] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32868412/

[4] https://www.ft.com/content/be583262-8bc7-4ad0-884c-792656093c22

[6] https://www.ft.com/content/be583262-8bc7-4ad0-884c-792656093c22

[12] https://hbr.org/2023/02/leading-with-compassion-has-research-backed-benefits

Introduction

We’re all aware of the inherent dangers in taking risks. We’re generally less aware of the dangers in playing it safe. In a business context, that’s because there used to be some merit to playing it safe –– to having ambition but pacing oneself, choosing a slow, incremental trajectory over a fast, steep one. As Doug Sundheim, author of Taking Smart Risks: How Sharp Leaders Win When Stakes are High, writes in Harvard Business Review: “The dangers of playing it safe aren’t sudden, obvious, and dramatic. They don’t make headlines. They…are hidden, silent killers.” [1]

Without risks we wouldn’t have put planes in the sky or man on the moon, nor have any of the everyday innovations we take for granted. But for each of history’s bold risk-takers, there were many more steady, risk-averse contemporaries sitting on the sidelines. And for a long time there was nothing wrong with that. As Steve Dennis, a strategic advisor and author of Leaders Leap: Transforming Your Company at the Speed of Disruption and Remarkable Retail, writes: “A heavy focus on business optimization and continuous improvement was eminently sensible. Until it wasn’t.” [2]

Things have changed.

Dennis writes of the large-scale disruption we have seen in recent years. Businesses like Airbnb, Netflix, Uber, and OpenAI did not simply emerge as major players in their respective industries. They totally reshaped how those industries functioned.

“Many brands that moved far more cautiously, or that are currently slow-walking their transformation efforts, have dramatically increased their risk of irrelevance,” Denniswrites. “Or even set themselves on a path to extinction.” [3]

Such companies tend to follow a path of what Dennis calls “infinite incrementalism”. Essentially, every year these companies would offer a slightly better version of what they had always done. That’s no longer enough. Not with the speed of change we’re accustomed to in today’s world.

Rishad Tobaccowala, the former chief digital officer of Publicis Group and author of Restoring the Soul of Business, says that in recent years we’ve moved through three distinct “Connected Ages.” [4] Each “Connected Age” changed how we connect and do business. We went from e-commerce to smart devices, to 5G, VR, the cloud, and AI.

The state of business today is unrecognisable from what it was twenty years ago. And who knows what it’s going to look like twenty years down the line? No one is quite sure and there are no guarantees. But the idea that one can just drift along at a snail’s place without being left behind feels increasingly naive. As the landscape shifts, businesses must shift with it.

Dennis concludes, “Faced with constant and accelerating change, doing what we’ve always done but just a little bit better may feel safe, but it is often the riskiest path we could possibly choose.” [5]

Rethinking our relationship to risk

To stop playing it safe, companies need to reassess their relationship with risk. Of course risk can bring failure. (As we’ve established, playing it safe can too.) But those failures don’t need to be failures. Through a shift in mindset, they can instead be viewed as opportunities for learning.

“If we are open to taking more risks, it’s more opportunity for diverse experiences and more opportunity to learn and grow as individuals,” says Jon Levy, author of The 2 AM Principle, speaking to Forbes. “It isn’t the success or failure, it’s who you become in the process.” [6]

This approach is in line with that of Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella. Nadella moved Microsoft from a “know it all” to a “learn it all” culture [7]. That meant that rather than condemning staff for taking risks that failed, he would reach out to congratulate them after a “failure”. What he understood that many don’t is that you can’t simply praise the risks that work and condemn those that don’t. You have to create an environment in which your team feels comfortable failing and doesn’t fear facing recriminations if things don’t work out. Such an approach can shift the mindset of the whole company.

Any cricket fans who witnessed the ‘Bazball’ revolution of the England team these past few years will have seen this approach in action. There was no change to personnel, just a change to messaging. If a player got caught on the boundary in the old administration they may be admonished for trying to hit a big shot. Under the new management, they were told “next time hit it even harder.” England had won just one Test from their previous seventeen prior to the change in approach. Following it, they won ten out of twelve.

Of course not all risk is good risk. There are many situations in which caution is a better option. The Silicon Valley mantra of “move fast and break things” has its uses, but it is not necessarily advisable to adopt it wholesale. As Dennisnotes, it might be better to move fast and fix things [8]. To do that, one needs to assess whether they are dealing with an actual risk or a perceived one.

Unlike actual risks, perceived risks are the ones we’ve bigged up in our minds out of a fear of the unknown. It’s not sending off that job application because you’re afraid you’ll get rejected; not trying that new strategy because you worry it might make you look stupid. Such fears are rational, human even. But they serve little purpose. As Eric Hutto, Chief Executive Officer at Diversified, writes in Forbes, “You can’t build a futuristic company when leadership has a legacy mindset that focuses on risk management over taking risks that could result in better performance.” [9]

One need only look at Amazon to see what can happen when a company takes a risk rather than settling for incrementalism. Jeff Bezos could easily have continued as a very successful online book retailer. Instead, he upscaled. The rest is history.

How to implement risk

A 2021 McKinsey study found that more than 80% of executives say innovation is among their organisation’s top three priorities, yet less than 10% say they are satisfied with their company’s performance. Meanwhile, 61% say their organisations are not adapting fast enough to stay ahead of disruption and 78% believe it is increasingly challenging to know which disruptive forces to prioritise. [10]

There is an appetite for risk. But that appetite is being outweighed by fear. The good news is that, ironically, there are ways to implement risk in a relatively risk-free way.

If you’re trying to cultivate a culture of experimentation, Dennis advocates for finding ways to “shrink the change” [11]. By that he means breaking complex and seemingly overwhelming initiatives into a series of more manageable pieces. In other words, don’t try to overhaul everything in one fell swoop. And don’t obsess over the final destination. Take it one step at a time.

Meanwhile, Sundheimrecommends creating a culture in which you question everything.

“What does this business look like in five years? What are our customers worrying about today? What will they be worrying about tomorrow? What are our employees seeing but not saying? Where are we communicating effectively? Where are we failing to communicate? What strengths aren’t we capitalizing on? What opportunities are we letting slip through our fingers? How would we try to beat ourselves if we were our competitors? What weaknesses would we exploit? And where are we settling for “good” when we should really be going for “great?”” [12]

Questioning everything helps ensure you don’t slip into a place of complacency and stagnation. As Sundheim says, it makes it “more uncomfortable to play it safe than to think critically and take risks.” [13]

Writing in Forbes, Rhett Power, CEO and Founder of Accountability Inc., recommends three risks that are usually worth taking, even for those who are generally risk-averse. They are: (1) Moving forward without substantial investor support (2) Hiring on a tight budget (3) Growing your business. [14]

Moving forward without substantial investor support forces one to focus on only the most essential components of their business –– a useful exercise for anyone. Hiring on a tight budget is important because it stops one from taking their team for granted, overloading them with work in the belief that they can pick up the slack. It might work short-term but long-term leads to burnout, resentment and lower-quality work. If you can’t afford to hire full-time, get someone part-time.

While acknowledging that growing one’s business too fast can be a nail in the coffin, Power says that “the risks associated with growth are worth the opportunity to see more success for your business and your team.” [15] To grow successfully, he recommends not conflating overheads with infrastructure and having an operational infrastructure that transcends your employees and management team.

The dangers of playing it safe

Taking risks is dangerous. But so is playing it safe. In a fast-moving global order in which the foundations that held up industries for decades can crumble almost overnight, infinite incrementalism can be a silent killer. Companies need to be open to risk.

To start embracing risk, businesses must first shift their relationship with it. Risk is not an opportunity for failure, it is an opportunity for learning. That does not mean moving recklessly. Rather, it means assessing whether a risk really could be perilous or that’s simply a perception. Companies want innovation. They need to accept that they’re going to have to take some risks to achieve it.

More on Risk

Innovation: Gains, Risks, and the Grey In Between

Sources

[1] https://hbr.org/2013/10/the-hidden-dangers-of-playing-it-safe

[2] https://hbr.org/2024/03/why-playing-it-safe-is-the-riskiest-strategic-choice?ab=HP-topics-text-28

[3] https://hbr.org/2024/03/why-playing-it-safe-is-the-riskiest-strategic-choice?ab=HP-topics-text-28

[4] https://hbr.org/2024/03/why-playing-it-safe-is-the-riskiest-strategic-choice?ab=HP-topics-text-28

[5] https://hbr.org/2024/03/why-playing-it-safe-is-the-riskiest-strategic-choice?ab=HP-topics-text-28

[6] https://www.forbes.com/video/5193863769001/why-you-should-take-more-risks/?sh=1a7db99e1351

[8] https://hbr.org/2024/03/why-playing-it-safe-is-the-riskiest-strategic-choice?ab=HP-topics-text-28

[10] https://hbr.org/2024/03/why-playing-it-safe-is-the-riskiest-strategic-choice?ab=HP-topics-text-28

[11] https://hbr.org/2024/03/why-playing-it-safe-is-the-riskiest-strategic-choice?ab=HP-topics-text-28

[12] https://hbr.org/2013/10/the-hidden-dangers-of-playing-it-safe

[13] https://hbr.org/2013/10/the-hidden-dangers-of-playing-it-safe

Introduction

In his latest book, AI: Unexplainable, Unpredictable, Uncontrollable, AI Safety expert Roman Yampolskiy highlights a core issue at the heart of our continual AI development. The problem is not that we don’t know precisely how we’re going to control AI, but that we are yet to prove that it is actually possible to control it.