Introduction

This article delves into the psychology of likeability, reviewing strategies to enhance engagement and foster better relationships. Drawing upon the latest research in social psychology, it explores how subconscious factors influence perceptions, the nuances of engaging in small talk, and the essence of a captivating presence. Discover how likeability can transform your personal and professional life.

The Psychology of Likeability

Understanding the essence of likeability can significantly alter our interactions both personally and professionally. Psychology unveils subconscious triggers that influence our perception of others. By grasping these mechanisms, we can refine our approachability and establish stronger bonds.

Subconscious Triggers

Our brains evaluate individuals based on subtle cues, such as body language and tone of voice. Maintaining eye contact, mirroring body movements, and displaying a warm, genuine smile are traits that foster trust and comfort. These actions shape our perceptions and increase likeability.

Mastering Small Talk

Engaging in seamless small talk is crucial for building rapport. Effective small talk hinges on active listening, asking open-ended questions, finding common ground, and using positive body language. These strategies foster trust and create meaningful connections.

The Power of Storytelling

Storytelling, a timeless art, has the remarkable ability to engage and persuade. By crafting compelling narratives, you can engage with your audience’s emotions, fostering a profound connection. Improve your storytelling by drawing from personal anecdotes, incorporating vivid imagery, and featuring relatable characters. This approach can transform a straightforward message into an indelible experience.

The capacity to develop and refine charisma and magnetic presence is a skill that evolves with practice. By integrating the subtleties of body language with the art of storytelling, you can unveil a level of charm and influence that will resonate with those around you.

“Charisma is not in the words you say, but in the way you say them.”

Unknown

| Charismatic Presence Techniques | Benefits |

| Mastering Body Language | Boosts likeability, trustworthiness, and approachability |

| Crafting Captivating Stories | Connects with the audience on an emotional level |

| Projecting Confidence and Composure | Inspires others to follow your lead |

Likeability in the Professional Realm

In the competitive arena of career advancement, the quality of professional likeability emerges as a crucial asset. It significantly enhances your ability to forge robust workplace relationships and cultivates a favourable professional image. This, in turn, paves the way for new opportunities and hastens your career progression. By refining your professional likeability, you can effortlessly manoeuvre through the corporate environment, thereby achieving your professional objectives with enhanced confidence.

Initiating the cultivation of professional likeability necessitates an understanding of its underlying psychological dynamics. It is the warmth, authenticity, and a sincere interest in others that naturally attract people. By sharpening your listening skills, maintaining a positive outlook, and offering sincere compliments, you can establish a compelling presence among your colleagues and superiors.

Another pivotal element of professional likeability is the mastery of small talk. Engaging in effortless, meaningful dialogue across diverse topics facilitates rapport building and leaves a memorable impact. Staying abreast of current events, industry trends, and shared interests equips you with conversation starters, enabling you to forge deeper connections with your peers.

Furthermore, cultivating charisma and a magnetic presence is vital for professional likeability. Attention to your non-verbal cues, the art of storytelling, and exuding confidence can create an aura of likeability that distinguishes you from others.

“Likeability is not a personality trait, but a skill that can be learned and honed over time. The more you invest in developing professional likeability, the greater the dividends you’ll reap in your career.”

Embracing the essence of professional likeability empowers you to navigate the workplace with heightened confidence, establish profound connections, and position yourself for sustained career success. Remember, the capacity to forge genuine connections is a skill of immense value, propelling you towards the pinnacle of your professional ambitions.

When Likeability in Leadership Backfires

While likeability is often seen as a key trait for effective leadership, it is unwise to select leaders solely on this basis, especially if it means neglecting other crucial predictors of leadership effectiveness, such as expertise, intelligence, and integrity. Here are three reasons why likeability in leadership can backfire:

- Likability May Mask Dark Side Traits: Perceptions of likeability can sometimes hide toxic traits. Individuals with narcissistic or psychopathic tendencies can appear charming and socially skilled, which might lead to their being mistakenly perceived as likeable.

- Mindless Conformity: Likeable leaders might encourage conformity rather than innovation. True leadership often requires challenging the status quo, which may not always align with being likeable.

- Results Over Popularity: Leaders overly focused on being liked may avoid making tough decisions. Effective leadership requires balancing likeability with the ability to make difficult choices and drive results.

Conclusion

Likeability is a powerful force that can transform personal and professional interactions. By understanding and leveraging the psychology of likeability, mastering small talk, and developing a charismatic presence, individuals can significantly enhance their influence and success.

Embracing likeability involves consistent practice and application in daily interactions. It is a skill that can be developed and refined over time, leading to more fulfilling relationships and greater professional achievements.

FAQ

What are the subconscious triggers that make people like me? Subconscious triggers include mirroring body language, maintaining eye contact, and expressing warmth through facial expressions and tone of voice. These actions significantly shape how others perceive you.

How can I improve my small talk skills? Key strategies include active listening, posing open-ended questions, sharing pertinent personal stories, and maintaining a positive, engaged attitude during conversations.

What are the secrets to projecting a charismatic presence? Projecting a charismatic presence involves mastering both verbal and non-verbal communication, such as confident posture, expressive hand gestures, and engaging storytelling.

How can I leverage likeability to enhance my professional success? Enhancing professional likeability involves active listening, offering sincere praise, fostering a positive work environment, and engaging in meaningful small talk.

What are the key benefits of developing greater likeability? Benefits include cultivating deeper relationships, expanding social and professional opportunities, and increasing influence and impact on those around you.

By mastering the art of likeability, individuals can unlock their full potential, becoming more respected, admired, and successful in their personal and professional lives.

More on Charisma

Introverts, extroverts and leadership with Karl Moore – Podcast

Dealing with Imposter Syndrome

Introduction

In 2005, David Foster Wallace, the celebrated author renowned for his lofty, intellectual style and profound, often humorously contempful explorations of the human experience (not to mention his trademark bandana), delivered a now-iconic commencement speech to the graduating class at Kenyon College. His speech was titled “This is Water” [1]. That title, seemingly banal, delivers a profound, even life-changing message (if the YouTube comments are to be believed, at least).

Wallace urges graduates to cultivate a deliberate awareness of the seemingly obvious, the everyday realities that often slip by unnoticed. He does so through a short and simple anecdote.

There are these two young fish…

Foster Wallace tells the story of two young fish swimming merrily along. On their journey, they encounter an older fish swimming in the opposite direction. The older fish nods and says, “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” The two young fish swim on for a bit before one turns to the other and asks, “What the hell is water?”

“The point of the fish story,” Foster Wallace explains, “is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about. Stated as an English sentence, of course, this is just a banal platitude, but the fact is that in the day to day trenches of adult existence, banal platitudes can have a life or death importance, or so I wish to suggest to you on this dry and lovely morning.” [2]

Modern water

The anecdote of the fish in water poignantly illustrates our tendency to take the fundamental aspects of our existence for granted. We live immersed in the water of our daily routines, oblivious to its very existence until someone points it out. The “water” in our lives could be anything –– the ability to have a meaningful conversation, the beauty of a sunrise, the simple act of breathing, all these cosmically miraculous aspects of the human experience that we steadfastly fail to recognise.

Foster Wallace goes into great detail in the speech laying out just how difficult it is to spot the water around us. And that was in 2005. In the subsequent years, the water, if at all possible, has grown more transparent and undetectable still. We live amongst an attention-sapping multimedia environment explicitly designed to absorb us. Smartphones and social media make it not just impossible to notice our settings but to acknowledge that we’re swimming at all. Our attention, the aspect of ourselves Foster Wallace goes to great lengths to say we should prize, protect and treasure, is a currency traded amongst Silicon Valley power brokers. Our attention is bought and sold behind our backs, often for all too cheap. And that is just one of the battles currently facing us.

We are also battling the cult of false positivity, staring blankly at a curated reality social media drip feeds us, feasting on slideshows and highlight reels of other lives we deem better than our own. We are repeatedly thrust into the twin states of feeling inadequate while simultaneously burning with a need to curate our own false reality online too. We must play along with the great lie or else allow our lives to appear lesser, mundane, forgettable. Pretty soon everything is distorted.

We are battling the fear of missing out, confronted with an endless need to stay connected, to check back in online for fear that we will be alienated and out of step with those around us if we fail to. It’s hard to be fully present in the moment when all the while you’re in it, you wish you were in another one.

We are battling our brains, most specifically the default mode network. This is our brain’s natural mode of operation that kicks in when we’re not actively engaged in a task. This mode often leads to ruminating on the past or worrying about the future, further pulling us away from the present moment.

In the context of such a society, Foster Wallace’s message about cherishing the ordinary becomes even more relevant. These factors combined create a constant undercurrent of distraction, making cultivating sustained awareness feel nigh on impossible. But it is doable. It just requires effort.

The benefits of making that effort are numerous.

The benefits of awareness

A recent study published in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine found that those who completed a mindfulness awareness program experienced less insomnia, fatigue, and depression after six weeks than those who received sleep education [3]. A study that was presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2022 reported that after participating in an eight-week mindfulness behaviour program, adults who had elevated blood pressure at the beginning of the program had significantly lower blood pressure and reduced sedentary time at their six-month follow-up. [4]

In the UK, it is estimated that as many as 30% of GPs refer patients to mindfulness training [5]. That’s because the benefits are well-documented and because in theory it’s simple (though as anyone who has tried focusing on the breath will tell you, it’s difficult to believe how quickly the mind drifts away).

By becoming more aware of our own thoughts and feelings, we can develop a deeper understanding of those around us. When we pay attention to the everyday details, we can cultivate a genuine appreciation for the beauty and wonder of the world. Being present allows us to make more conscious choices, rather than acting on autopilot, and can reduce the amount of time we waste ruminating on the past and worrying about the future.

As Foster Wallace puts it, “Learning how to think really means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience” [6]. The simple act of acknowledging the “water” of our lives can lead to a more meaningful and fulfilling existence.

Cultivating Awareness

Being aware of one’s surroundings does not just happen. It is a conscious act, and a challenging one. As Foster Wallace puts it, “People who can adjust their natural default setting this way are often described as being “well-adjusted”, which I suggest to you is not an accidental term” [7]. So how does one become well-adjusted? How does one find a way to spot the water around them in a world designed to distract us?

As previously noted, one option is mindfulness. The availability of mindfulness apps makes it easy to get started. Incorporating just ten minutes a day into your daily routine can change your perspective in monumental ways.

Another option is gratitude exercises. Taking time each day to reflect on things you’re grateful for can shift your focus to the positive aspects of your life. It’s a useful countermeasure against negative thinking.

If your distraction is not just internal but external –– ie you are overly occupied by your phone and digital spaces –– it could be worth attempting a digital break. You don’t have to go cold turkey. You could start small by saying “I’m not going to use my phone for half an hour before bed.” Then extend that period out or add further half-hour breaks to your day, during lunch or after work for example. A useful tip is to put your phone in another room during any detox to remove the temptation. Out of sight really is out of mind.

Try focusing on your senses. This is a step that will be recommended to you in mindfulness practices but you can do any place, any time, by yourself. Simply make the choice to notice what surrounds you –– sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures. This simple act can anchor you in the present moment.

Make a conscious effort to engage in activities that require focus. Activities like reading, spending time in nature, or creating art can demand your full attention, fostering a state of mindfulness or even flow state. It’s time better spent than scrolling.

Observe your thoughts rather than judging them. This too is a pillar of mindfulness practice but something you can do alone. Every thought you’ve ever had has passed away, the one you’re currently lost in will too. Try to notice your thoughts as a passive bystander rather than lending them overdue creed, and do the same with people too. When interacting with others, try to observe them without judgement. It can lead to deeper connections and a better understanding of the people around you.

That’s a lot of examples but, as noted, most of them can be practised even for just a few moments throughout the day –– it’s just about breaking the spell of thought and noticing what’s around you. Still, it’s recommended you start small. Don’t try to overhaul your life overnight. Begin with easy, manageable changes, like taking a few mindful breaths throughout the day.

None of these strategies are a one-time fix, rather a lifelong practice. By incorporating any or all of them into your daily routine, you can cultivate a greater sense of awareness and begin to truly appreciate the “water” of your existence. At the risk of sounding guru-adjacent, it can help set you free from the prison of your mind. As Foster Wallace says, “The really important kind of freedom involves attention and awareness and discipline, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.” [8]

This is water

David Foster Wallace’s “This is Water” speech serves as a powerful reminder to appreciate the seemingly mundane aspects of life. In a world overflowing with distractions, cultivating awareness requires conscious effort. It is difficult. But the rewards are substantial.

By adopting the practices outlined above, we can embark on a lifelong journey of self-discovery, increased appreciation, and a deeper connection with ourselves and the world around us. The “water” of our lives is always there, waiting to be acknowledged. It’s up to us to become the “older fish” who can see it, savour it, and appreciate the profound beauty in the ordinary.

More on Mindfulness

Stress Management and Leadership Through Mindfulness

Breathing, Cold Exposure, and Mindfulness with Níall Ó Murchú

Mindfulness, Meditation and Compassion in the Workplace and in Life with Scott Shute – Podcast

Sources

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DCbGM4mqEVw

[2] https://fs.blog/david-foster-wallace-this-is-water/

[6] https://fs.blog/david-foster-wallace-this-is-water/

[7] https://fs.blog/david-foster-wallace-this-is-water/

[8] https://fs.blog/david-foster-wallace-this-is-water/

Introduction

Capitalism has been around for decades. The field of research which seeks to understand the concept of capitalism, has often been defined as the field of comparative political economy as a result of the focus on differences in institutional settings which determine economic outcomes (Regini, 2014). These differences are frequently seen not as products of business decisions but as legacies from various historical contexts. Today, notable differences remain in the industrial relations systems of several countries globally (McLaughlin and Wright, 2018).

Defining Capitalism

Definitions of capitalism have varied over the years since the 19th century. It has been used to characterise the emerging shape of the modern economy and the transformation of society as a whole. Capitalism is an economic system in which private individuals own property and operate according to their own interests, with supply and demand freely determining market prices in a way that can best serve society (Fund, 2017). In the twentieth century, the term “capitalism” became more frequently used to express political perspectives on the desirability and permanence of capitalism as opposed to socialism (Delanty, 2019).

Liberal Market Economies & Coordinated Market Economies

Liberal Market Economies (LME) and Coordinated Market Economies (CME) are two forms of capitalism that can be applied to both past and present theories of capitalism (Crouch, 2005). The concept of a liberal market economy, originally defined by Hall and Soskice, is characterised by the adoption of market mechanisms and agreements to manage relationships among suppliers and buyers. Additionally, they identify coordinated market economies, which are characterised by bargaining-based labour relations and arrangements that reflect employees’ longer-term commitments (Lansbury and Bamber, 2020). LME economies rely on labour markets that set wages through competition and typically have less regulation to protect employees and provide them with security (Crouch, 2005).

Social & National Factors in Relation to Market Economies

The developed world is often divided into liberal market economies (LMEs), such as the UK and USA, and coordinated market economies (CMEs), such as Japan and Scandinavian countries (Dibben and Williams, 2012). However, it is important to recognise that these approaches to capitalism have limitations and often do not account for differences in the social or political makeup of each country. Lansbury and Bamber (2020) highlighted that the institutional bases on which German and Japanese corporate governance arrangements are built, as well as the historical events that formed them, differ despite generating similar outcomes. This illustrates the importance of considering social and national influences on industrial relations based on the country in question. Despite pressures for convergence in industrial relations systems, Europe has maintained distinct national industrial relations systems (Black, 2005). Social and national factors are ultimately what must be taken into consideration when analysing national industrial relations systems (Lansbury and Bamber, 2020).

The Effect of External Forces on the Economy

Prices and wages typically take a while to adjust to the forces of supply and demand, with demand playing the largest role in determining economic growth (Hackemy 2017). The economy can transition between major phases of development and contraction through boom-and-bust cycles, which are a feature of economic growth (Hakemy, 2017). Today many multinational corporations are faced with the western style model of capitalism (Werhane, 2000). Businesses can pursue their ambitions competitively without the hassle of restrictions and undue regulations surrounding labour restrictions which can result in growth and economic good in every country (Werhane, 2000). It is important to remember that in this context, capitalist economies and industrial relations systems cannot be generalised for globally. The perception of what is good and beneficial to the employee and multinational corporations will vary from country to country based on the social and cultural norms (Werhane, 2000).

Conclusion

Capitalism can be useful in understanding the inner mechanisms of an economy. LME’s & CME’s illustrate than capitalism can be organised and function in many ways. Ultimately it is essential to consider the multitude of factors which can contribute to a successful economy including social, national and historical context.

Sources

Baran, P.A. (1963) ‘Review of Capitalism and Freedom’, Journal of Political Economy

Black, B. (2001) ‘National Culture and Industrial Relations and Pay Structures’, LABOUR, 15, pp. 257–277. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9914.00164.

Black, B. (2005) ‘Comparative industrial relations theory: the role of national culture’, The International Journal of Human Resource Management Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190500143980.

Calayton S. Rose and Rebecca Henderson (2018) Note on Comparative Capitalism – Technical Note – Faculty & Research – Harvard Business School, Harvard Business School. Available at: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=48459 (Accessed: 7 May 2023).

Crouch, C. (2005) ‘Models of capitalism’, New Political Economy, 10(4), pp. 439–456. Available at: hTps://doi.org/10.1080/13563460500344336.

Crouch, C., Schröder, M. and Voelzkow, H. (2009) ‘Regional and sectoral varieties of capitalism’, Economy and Society, 38(4), pp. 654–678. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140903190383.

Delanty, G. (2019) ‘The future of capitalism: Trends, scenarios and prospects for the future’, Journal of Classical Sociology, 19(1), pp. 10–26. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1468795X18810569.

Denis, A. (2004) ‘Two rhetorical strategies of laissez-faire’, Journal of Economic Methodology, 11(3), pp. 341–357. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1350178042000252983.

Dibben, P. and Williams, C.C. (2012) ‘Varieties of Capitalism and Employment Relations: Informally Dominated Market Economies’, Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 51(s1), pp. 563–582. Available at: hTps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468- 232X.2012.00690.x.

Feldmann, M. (2019) ‘Global Varieties of Capitalism’, World Politics, 71(1), pp. 162–196. Available at: hTps://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887118000230.

Fund, I.M. (2017) Back to Basics: Economic Concepts Explained. International Monetary Fund.

Gollan, P. and Patmore, G. (2013) ‘Perspectives of legal regulation and employment relations at the workplace: Limits and challenges for employee voice’, Journal of Industrial Relations, 55, pp. 488–506. Available at: hTps://doi.org/10.1177/0022185613489392.

Hakemy, S. (2017) An Analysis of Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom. CRC Press. Hancké, B. (2009) Debating Varieties of Capitalism: A Reader. OUP Oxford.

Hughes, S. (2005) ‘The International Labour Organisation, New Political Economy, 10(3), pp. 413–425. Available at: hTps://doi.org/10.1080/13563460500204324.

Kano, L., Tsang, E.W.K. and Yeung, H.W. (2020) ‘Global value chains: A review of the multi- disciplinary literature’, Journal of International Business Studies, 51(4), pp. 577–622. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00304-2.

Kollmeyer, C. (2021) ‘Post-industrial capitalism and trade union decline in affluent democracies’, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 62(6), pp. 466–487. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/00207152221086876.

Lansbury, R.D. and Bamber, G.J. (eds) (2020) International and Comparative Employment Relations: National regulation, global changes. 6th edn. London: Routledge. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003116158.

McLaughlin, C. and Wright, C.F. (2018) ‘The Role of Ideas in Understanding Industrial Relations Policy Change in Liberal Market Economies’, Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 57(4), pp. 568–610. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12218.

Regini, M. (2014) ‘Models of Capitalism and the Crisis’, Standing, G. (2008) ‘The ILO: An Agency for Globalisation?’, Development and Change, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2008.00484.x.

Werhane, P.H. (2000) ‘Exploring Mental Models: Global Capitalism in the 21st Century’, Business Ethics Quarterly, 10(1), pp. 353–362. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/3857720.

Yang, I. (2015) ‘Positive effects of laissez-faire leadership: conceptual exploration’, Journal of Management Development, 34(10), pp. 1246–1261. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-02-2015-0016.

Introduction

A new boss taking over can be difficult. Change often is. For employees, the promise of fresh perspectives and strategic shifts can be exciting. But the uncertainty surrounding changing dynamics and expectations can also be unsettling, for seasoned staff and recent hires alike. For those who liked their old boss, the new one is a daunting prospect. And even those that didn’t face an element of “the devil you know.” At such a juncture, all employees will be sat around the office contemplating what a change of leadership means for their futures.

Successfully navigating a leadership transition requires a proactive approach to ensure continued productivity and career satisfaction. How do you build a relationship with a new leader? How do you help ensure a smooth transition? In the worst case scenario, how do you spot a leader who isn’t going to serve you and what can you do to counter that?

Understanding the new leader

It’s natural for employees to want to know as much as possible about their new leader as quickly as possible. This is the person whose expectations they will now need to be meeting; they’ll want to know what those expectations are. Equally, given there is such a wide variety of leadership styles, they may wish to adjust their temperament or approach accordingly.

In the modern world, employees can often get a decent sense of their new boss’s approach and values in advance of their arrival through their online presence. Most people have a LinkedIn profile through which their new employees can evaluate their posts to get a sense of their leadership style, past successes and communication preferences. Even just a look at their employment history can provide a sense of their trajectory and offer hints as to their approach.

Equally, employees may be able to track down their boss’s personal social media accounts by way of Instagram, X (Twitter) or Facebook. Wise leaders will make these accounts as difficult to track down as possible. And wise employees may not want to risk exposing themselves as having perused their new boss’s personal account in advance of their arrival.

Following the new leader’s commencement comes the bedding in period, which depending on the leader and company in question can be a matter of weeks or months (one would hope not years). This period can be awkward and overly formal, with employees tip-toeing around the new boss and vice versa, everyone trying to figure the other out, fearful of earning themselves a spot in the bad books. Conversely, they can be overly contested, with a new leader looking to establish a foothold through shows of strength, maybe even ruthlessness. Meanwhile their more fiery underlings will either push back directly or raise dissent amongst their cohorts at every opportunity.

Neither of these approaches is ideal, though the first is obviously preferable. It’s only natural that things begin tentatively. Employees should try to make use of that early period to establish an amiable rapport with their new boss and to work out what kind of leader they are. Gather information, observe closely, and ask questions during initial meetings and interactions. How do they communicate? Are they direct and concise or more collaborative and open-ended? Do they favour quick decisions or encourage team input? Actively listen to their vision for the company and their priorities. Don’t hesitate to schedule a one-on-one meeting to clarify expectations or gain a better understanding of their vision for the department or company as a whole.

Building a positive working relationship

To state the obvious, you want to impress your new boss. And you want to do so at the earliest opportunity you can.

“Recognize that people do draw some impressions about you pretty quickly,” says Karen Dillon, coauthor of Competing Against Luck and the HBR Guide to Office Politics [1]. But how do you make sure those first impressions are positive?

Michael Watkins, chair of Genesis Advisors and author of The First 90 Days, advises you put yourself in your new boss’s shoes. “Keep asking yourself, ‘How can I help them get up to speed faster?’” [2]

Writing in Harvard Business Review, Carolyn O’Hara offers some practical advice as to how to build a strong rapport from day one [3]. She suggests (1) looking for common ground (2) being empathetic to your new boss’s situation (3) not laying it on too thick (or thin) (4) helping them achieve early wins, and (5) coming armed with solutions, rather than problems.

Equally, experts recommend discerning your new boss’s communication style early. “The sooner you get a sense of how they prefer to be communicated with, the better,” says Watkins [4]. Do they prefer email, calls, texts, or in-person discussions? Do they like to weigh all of the pros and cons before making a decision, or do they want to hear what you’d suggest? Knowing this information will help you avoid misunderstandings that could complicate your work or put you in a difficult situation.

Dillon says the best way to discern this information is simply to outright ask. “Even if they don’t have a great answer because they’re still figuring it out,” she says, “they know that you’re open to it and that you’re approaching them with the attitude, ‘I want to be effective for you.’” [5]

Onboarding a new manager

If you’re a long-serving member of your company, or if your new boss has previously worked in other fields and is less familiar with their new territory, they may be reliant on you to get them up to speed as to how the company functions. This onboarding process is pivotal. If you help your new boss hit the ground running, they’ll be indebted for you going forward. If you make life tricky, the opposite is likely to be the case.

According to research from Egon Zehnder, there are three main reasons why new leaders derail: 1) They fail to understand how the organisation works; 2) They don’t fit with the organisational culture; and 3) They struggle to forge alliances with peers [6]. A helpful, ambitious employee can see to it that their new leader doesn’t fall into any of those trappings.

In Harvard Business Review, Rose Hollister and Michael D. Watkins write that their research shows that those challenges were not dissimilar whether said new boss was an external hire or had received an internal promotion. Leaders they surveyed “said internal promotions were 70% as difficult as coming in from the outside.” [7]

Hollister and Watkins diagnose three fundamental types of learning when starting a new role: technical, cultural, and political [8].

They say that technical learning is about understanding what it takes to succeed in the job. In other words, getting up to speed with the specifics of the organisation’s roles, goals, capabilities, KPIs, and performance, as well as any key products, technologies, systems or customers. Cultural learning is about understanding the key behavioural norms that govern company norms, if there is a certain in-house style or process, for example. Political learning is about identifying the key stakeholders and internal relationships or hierarchies, and clarifying the decision-making processes.

When to be worried

While adjusting to a new leader requires flexibility and patience, certain situations may warrant concern. It could be that your new leader starts showing signs of misalignment with the company culture, or quite simply that they’re not a good leader or person. The impact of that will obviously be felt around the office and could negatively affect your career. So, what kind of signs should you be looking out for?

An obvious indicator that your new boss is not the right fit is if they display unethical behaviour. Some of that may be obvious and easily dealt with –– someone who openly partakes in harrassment, bullying or discrimination should be swiftly dealt with in the modern world. But equally look out for other more nebulous traits such as favouritism, a punitive streak, unpredictable moods or microaggressions.

If you notice these traits but sense they are down to a misunderstanding, it could be worth raising your concerns with the individual in question. If the signs are more pernicious, it may be time to report your concerns to human resources. If they fail to act, start looking elsewhere; anyone who works for a long period of time under a bad boss in a toxic environment tends to bear the scars. It’s not worth it.

Navigating new leadership

The arrival of a new leader presents a unique opportunity for both the individual and the organisation. While initial uncertainty is natural, a proactive approach can transform this transition into a springboard for growth and success. By understanding your new leader’s style, building a positive working relationship, and consistently demonstrating your value, you can position yourself for continued success within the changing landscape.

Remember, your career growth is ultimately your responsibility. If the new leadership creates an environment that hinders your professional development or well-being, don’t be afraid to explore new opportunities that better align with your career goals. The skills you develop during this transition, such as effective communication, adaptability, and a willingness to learn, will serve you well throughout your career.

More on Change Management

Mastering Change and Complexity: Strategic Leadership in an Uncertain Business World

Pioneering Change : A Case Study of Jeff Bezos Transformational Leadership at Amazon

Sources

[1] https://hbr.org/2016/10/how-to-build-a-strong-relationship-with-a-new-boss

[2] https://hbr.org/2016/10/how-to-build-a-strong-relationship-with-a-new-boss

[3] https://hbr.org/2016/10/how-to-build-a-strong-relationship-with-a-new-boss

[4] https://hbr.org/2016/10/how-to-build-a-strong-relationship-with-a-new-boss

[5] https://hbr.org/2016/10/how-to-build-a-strong-relationship-with-a-new-boss

[7] https://hbr.org/2023/02/how-to-onboard-your-new-boss

[8] https://hbr.org/2023/02/how-to-onboard-your-new-boss

Introduction

It’s a painful moment. You’ve gone from the sun and shore, waves crashing against the sand while you sip on a fruity cocktail, to the harshly lit office, two screens in front of you, a litany of meetings in the diary and a seemingly bottomless email intray. It’s the return to work from holiday, and for a lot of people it’s hell.

Re-entry shock, holiday hangover, call it what you will. For a lot of us it’s hard to not be overwhelmed by the stark transition, harder still to actually hit the ground running. These return periods often result in a drop in productivity, a slump in mood, and a sense of disconnection.

But there are ways to avoid the negative spiral a return to work can bring. With a well-planned post-holiday transition, you can turn this potentially stressful time into an opportunity for rejuvenation and renewed focus. By implementing strategic measures, both employees and businesses can benefit from a smoother, more productive return to work.

The need for holiday

Sometimes during this draining return period we think, “why did I even take that holiday at all?” We convince ourselves it wasn’t worth the stress and that it would have been better to keep stubbornly plodding along without a break than face such a contrasting yin and yang.

As an example, senior advisor and executive coach Darin Rowell, EdD, quotes his client “Leslie” in Harvard Business Review. “Coming back from vacation almost makes [it] seem not worth it. For me, it’s like psychologically accelerating from a cruising pace of 30 mph to a speed of 80 so I can get through my inbox, catch up on all the meetings I missed, and reconnect with my neglected clients. And that’s on top of the guilt I’ve been feeling about overburdening my team while they’ve been covering for me.” [1]

Leslie’s thinking is common, but misplaced. Holidays are worth the pain of returning, even if you’re overwhelmed. Rest is vital, not optional. Refusal to commit to proper R&R can have profoundly negative consequences.

As Rowell writes, “research shows that those who don’t take the opportunity to rest, recharge, and recover are at higher risk of exhaustion, low motivation, poor performance, and burnout, while those who engage in regular periods of work recovery enjoy better sleep, higher job satisfaction, more engagement, and higher job performance.” [2]

Meanwhile, studies have shown that women tend to be less likely to use all of their allotted holiday days as compared with men. [3]

“In general, women tend to experience more guilt and are less confident than men, so that may hold women back from feeling like they can ask for and have permission to take time off,” says Fiona Murden, founder of Aroka, an organisational psychology consultancy, and author of Defining You. [4]

Given that studies show that workers who use their vacation days may be more productive and creative, as well as more likely to get a raise and receive higher performance reviews, it’s vital that all workers take proper time off [5]. But especially important women feel free to, or else we risk expanding an already too large gender divide.

Why do we slump?

It’s all too easy upon our return to lay the blame for our disconnection at our own feet –– we didn’t plan well enough, we didn’t check our emails or properly delegate, we had too much fun away from the office and are now reaping what we sewed. This melodramatic self-flagellation serves no one, and is fundamentally misplaced.

It’s only natural for the return to work life to be difficult. Holidays disrupt our biological rhythms and cognitive functions. Jet lag from travel, irregular sleep patterns, and changes in daily routines can all affect our ability to reintegrate into work. For instance, altered sleep cycles can impact our circadian rhythms, leading to fatigue and decreased cognitive function. Additionally, the pleasure of holiday activities boosts dopamine levels, creating a stark contrast when returning to routine tasks.

Additionally, our brains quite literally exaggerate the realities of day-to-day life, making the return to the mundane seem disproportionately more anxiety-inducing and depressing than it actually is. Indeed, according to Dr. Melissa Weinberg, a research consultant and psychologist specialising in well-being and performance psychology, this exaggeration of the brain that exacerbates our post-holiday blues is actually a sign of healthy psychological functioning.

“It’s just one of a series of illusions our brain fools us into believing, in the same way we think bad things are more likely to happen to others than they are to us. Somewhat ironically, the capacity to fool ourselves every single day is an indication of good mental and psychological functioning,” sh explains in The New Daily. [6]

“So, whether we did enjoy our holiday, and whether we’d rather be on vacation than back at work, our brain is wired to make us believe that we did, or that we would. In doing so, we pay the emotional cost for a well-enjoyed break, and we experience a comedown toward our baseline of well-being,” she explains.

That’s not to mention the emotional toll of time off. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, 64% of people report being affected by holiday depression, and it’s most often triggered by financial, emotional, and physical stress of the season. [7]

The stress of holiday spending, combined with the abrupt end of relaxation and leisure, can lead to post-holiday blues. Adjusting back to work routines can feel daunting, and the emotional high of the holiday season may make the return to daily responsibilities seem even more monotonous –– you’re seeing the nine to five you were accustomed to with fresh eyes. It takes some time to fall back into the routine.

Negative impact

Needless to say, the post-holiday slump impacts the business as well as the returning employee. Decreased productivity can lead to missed deadlines and a backlog of work, while disengaged employees are more likely to consider leaving their jobs, increasing turnover rates. This period can also disrupt team dynamics and project timelines, affecting overall business performance. As such, it’s important we have plans in place to ensure our reintegration to working life is as smooth as possible.

Strategies for a smooth transition: Delegate

The first step to a smooth reintegration comes well before you’ve even set off. Once those rest days are in the diary, you want to inform those around you of the timings of your absence and ensure you’ve got the right people in place to cover your assignments. How you approach that will vary depending on your seniority. A manager will need to ensure someone is there in their stead to oversee operations. For a more junior member of the team, it’s best to have your manager do the delegating for you rather than take it on your own back; they know the strengths of the team better than you do.

A lot of the stress of returning post-holiday is the mountain of work that awaits you. Having a prepared and trusted set of delegates on top of the detail alleviates that pressure. Either they’ll have covered all your work, or will have been sufficiently across the detail that they can brief you on what you’ve missed so you’re not scrambling through your inbox searching for anything urgent.

Strategies for a smooth transition: Don’t overdo it

When we first return to work, it’s tempting to want to make up for lost time. That often means we end up overdoing it during our first week or even day. It’s understandable to want to cover all that lost ground right away. As Rowell writes, “the urge to overwork stems from a well-meaning effort to relieve team members of the extra work they were covering for you, or a desire to demonstrate that even though you were away, your commitment remains high and you’re still valuable to the organisation.” [8]

But overworking “can leave you boomeranging from one extreme to the other, which increases stress and actually undermines your efforts to catch up” [9]. Rowell recommends taking at least a day to recover after your holiday before you start working again so you can mentally and physically prepare for the change in environment.

Strategies for a smooth transition: Allow yourself a catch-up day

Once back in the office, Murden recommends using that first day back as a buffer day in which you don’t schedule any calls or meetings. “Unless it’s an emergency,” she says, “use this day to get organised.” [10]

David Henzel, a member of Forbes’ Young Entrepreneur Council, agrees. He says day one should be solely for catching up and reimbursing yourself in the worklife, with zero meetings. His aim is to be at “inbox zero” aka having zero pending messages by the end of the day. He says “taking this time to catch up on the first day back results in the mental clarity to properly plan out the remainder of the week and provides the momentum to be at your peak performance as soon as possible.” [11]

Strategies for a smooth transition: Exercise healthy boundaries

Another member of the Forbes’ Young Entrepreneur Council, Carry Metkowski, advises making use of one particularly helpful word once you’re back: No. There will be meetings you don’t need to attend, tasks that can wait. Don’t take on more than you can chew. Show some judgement and put the more menial elements of your workload on the backburner.

“While saying “no” can sometimes create a little discord at the moment,” she says, “the extra emotional reserves you’ll have to take care of more important things will be well worth it.” [12]

Strategies for a smooth transition: Reestablish a routine

A lot of the discord that comes in the wake of a holiday stems from the fact that your long-established routine has been disrupted. The key to reintegrating swiftly is to find it again. That means waking up at the usual time, undertaking any external activities you usually partake in, such as exercising or meditating pre- or post-work, and generally committing to your familiar habits.

This disciplined and consistent approach is crucial to regaining focus and efficiency,” says Izabela Lundberg of the Legacy Leaders Institute, “helping you tackle work challenges with renewed energy, passion and success.” [13]

Rest isn’t optional

Perhaps Rowell’s most essential advice is that, should you find yourself in a working environment that discourages time away, or that rewards employees for excessive hours and self-sacrifice while punishing those who take their legally-mandated holiday, you leave.

“This kind of unhealthy work environment will leave you ripe for exhaustion and burnout,” he writes. “If you can’t leave right away, start creating an exit strategy” [14]. You deserve time off. Any company that fails to acknowledge that or correctly honour it isn’t worth your time.

Returning refreshed

While the initial return to work after a holiday can feel jarring, it doesn’t have to be a period of dread. By viewing this time as an opportunity for rejuvenation and renewed focus, both employees and businesses can benefit.

Rest isn’t a luxury, it’s a necessity. Businesses that prioritise employee well-being by encouraging proper time off and fostering a supportive work environment ultimately reap the rewards of a more engaged and productive workforce.

However, the responsibility doesn’t solely lie with employers. Employees must also be proactive in creating a smooth transition. This includes planning ahead, delegating tasks, and prioritising well-being during the first week back. Remember, it’s okay to say “no” to additional workload and to focus on reestablishing a healthy routine.

By following these strategies, we can transform the post-holiday period from a dreaded slump into a time for renewed energy and a successful return to work.

More on Rest

How Much Should You be Working?

Stress Management and Leadership Through Mindfulness

Sources

[3] https://www.fastcompany.com/90199683/theres-a-gender-gap-in-vacation-time-too?

[4] https://www.forbes.com/sites/shelleyzalis/2018/07/24/vacation-is-good-for-you-and-your-company/

[6] https://thenewdaily.com.au/life/wellbeing/2017/01/15/post-holiday-blues

[7] https://www.healthcentral.com/condition/depression/post-holiday-depression

[10] https://www.forbes.com/sites/shelleyzalis/2018/07/24/vacation-is-good-for-you-and-your-company/

Introduction

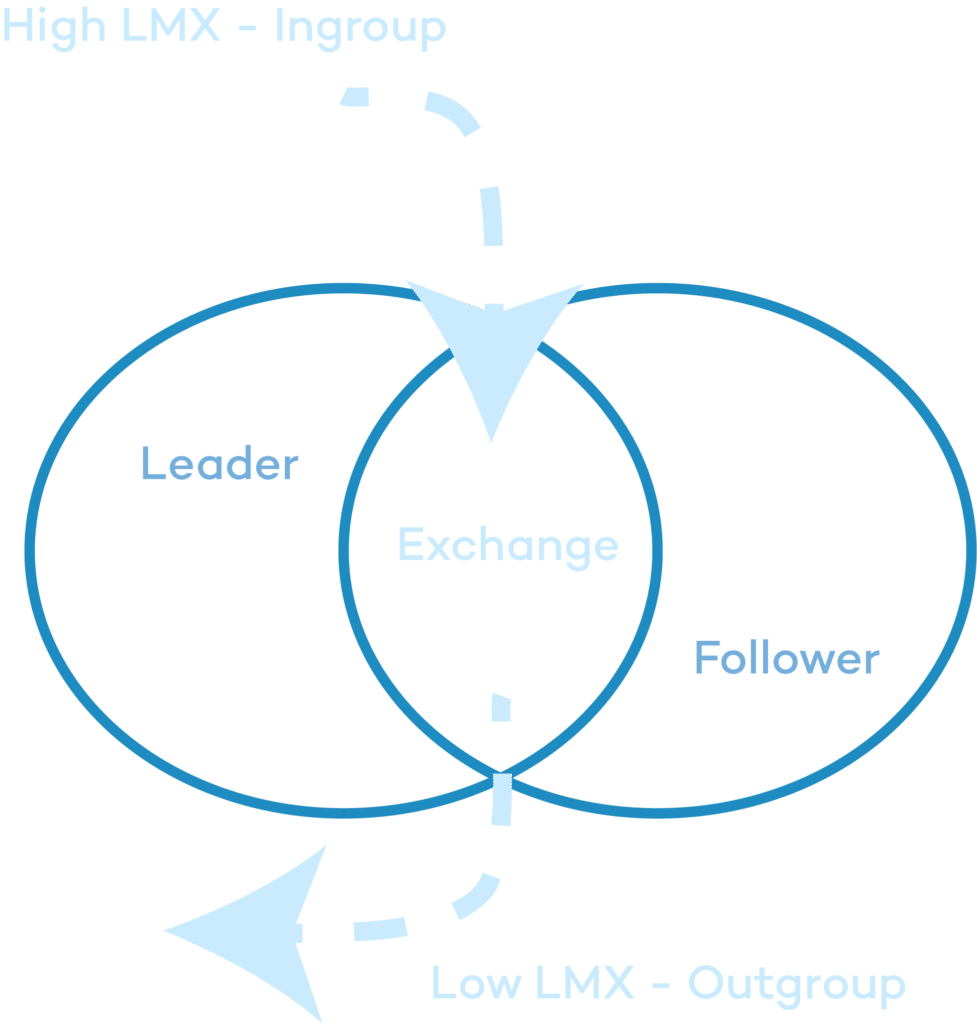

Leader Member Exchange (LMX) is a theory which focuses on the quality of the relationship between superior (leader) and subordinate (employee). The theory supports an ingroup, midgroup and outgroup (Horan et al., 2013). Employees within the ingroup may experience higher levels of LMX which is linked to increased confidence and positive relations; whilst outgroup interactions are characterised by low trust and minimal support (Horan et al., 2013).

Outgroups V Ingroups

In circumstances where employees do not develop a positive reciprocal relationship with their leader, they are said to belong to the outgroup. The outgroup refers to subordinates who are subjected to negative reinforcements from the leader and do not benefit from a rich relationship with their leader (Farr-Wharton et al., 2018). Due to the leaders’ time constraints, these relationships quickly form and range in quality from lower to higher exchanges (Deluga, 1998).

Leaders typically use their formal authority within organisations to communicate and instill shared values among their employees (Deluga.,1998). In exchange, employees work hard to fulfill the criteria of their clearly specified roles. There are several interpersonal factors present in these dealings, including mutual trust, loyalty, and close communication (Deluga.,1998).

Influence of High LMX on Employee Motivation

According to Farr-Wharton, Brunetto, and Shacklock (2012), the ideal situation with LMX is for employees to have high quality relationships, which will then yield the greatest benefits for both parties. LMX requires a perception of trustworthiness from the employee based on their leader in order for a high quality relationship to be facilitated (Chen et al.,2012). Emphasising the significance of superior LMX is crucial for leaders, as it has been associated with enhanced levels of competence and autonomy, consequently fostering heightened intrinsic motivation (Xie et al., 2020).

In relation to the LMX model, leaders should make use of a framework of social exchange in which connections are built with employees and knowledge is shared (Kim et al., 2017). Trust & social exchanges which occur as a result of high LMX can provide the leader with an insight into the employees thought processes with regard to their level of knowledge (Whisnant and Khasawneh, 2014). This can also help leaders navigate the areas in which employees require further support and guidance. From a leadership standpoint this is a valuable perspective as it identifies areas where employees require support which in turn fosters increased motivation and a sense of value within the organisation.

More on Trust & Autonomy

Why You Should Delegate – And How To Do It Effectively

Leadership in Focus: Foundations and the Path Forward

Sources

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1998-02680-005

https://www.jstor.org/stable/26536455

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7655925/

https://academicjournals.org/journal/AJBM/article-full-text-pdf/042449669944

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2012.00198.x

Introduction

According to PwC’s financial wellness survey of 2023, 60% of full-time employees are stressed about their finances. That figure is even worse than it was during the pandemic. The situation is so bad that 47% of employees earning $100,000 or more a year answered that they, too, were stressed about their finances [1].

44% of full-time employees say inflation has had a major or severe impact on their financial situation over the past year, 49% find it difficult to meet household expenses on time each month, and among employees carrying credit card balances, 44% say they struggle to make minimum payments on time each month [2].

The numbers are startling, and not just in the US. In Ireland, 81% of employees say they find money matters stressful [3].

It’s the paradox of money. It makes the world go round, is utterly pivotal to our ability to live with dignity, and yet it’s forever been a taboo. We should not talk about money. It’s poor etiquette socially – perhaps understandable – but even in our work environments the general consensus is that our employer gives us a salary, which every year or so we may renegotiate, but outside of that the topic should be avoided.

But to resuscitate financial health from its current flatline, that needs to change. Research commissioned by Bank of Ireland revealed that 88% of young people learn financial literacy and money management skills predominantly from their parents. Only 57% said they learned from teachers and 25% from online resources [4].

The disadvantages of that are obvious. If one’s parents – who likely were not given a financial education themselves – are not financially literate, their flaws will be passed down.

Ireland’s financial literacy score sits at 54%, well below neighbours and allies like the UK, Germany and Denmark. Troublingly, the 18-34 bracket scored lowest on financial literacy (48%), with over 65s scoring highest (58%) [5]. Sure, part of that boils down to life experience, but it also signals that this is an issue that is not going to resolve itself any time soon.

Cause for concern, too, is that women’s financial literacy scores were almost 10% lower than men, figures which are reflected internationally. A Swedish survey raised the issue of “stereotype threat”, meaning that as a result of women believing that their gender was worse at handling money, they in turn made worse financial decisions. The survey showed that amongst girls aged 13 to 15, financial literacy deteriorated as stereotype strength increased [6]. It takes active steps to reverse the trend.

Financial wellness programmes

Liz Davidson, Financial Finesse founder and CEO, says that, “Employee financial stress is at the greatest level it’s been since the Great Recession” [7].

She suggests the only way to combat this is for companies to adopt employer-sponsored financial wellness programmes. They’re no longer simply nice to have, she says. They’ve become an “imperative.”

The BrightPlan Wellness Survey of 2022 found that financial wellness programmes were now the number one most-wanted benefit among employees, more so than mental health initiatives or time-off programming [8].

And yet, a Transamerica Institute report found that while 77% of workers view financial wellness programmes as an important benefit, only 28% of employers offer them [9].

One positive is that the stigma around such programmes seems to be dampening. PwC notes that when it started its annual financial wellness survey in 2012, only 51% of workers whose employer offered financial wellness services had used them. By the 2023 survey that number had risen to 68% [10]. Just 33% of employees now find it embarrassing to ask for guidance or advice regarding their finances, compared with 42% in 2019 [11].

Among workers who have even attempted to estimate how much money they will need to save in order to retire, a recent report found that 45% simply “guessed” the amount and only 29% have a written plan for how to achieve it [12]. The situation can’t be fixed fast enough.

How to approach financial wellness programmes

Elements of financial education that companies should be focusing on include budget and savings planning, how to create attainable financial goals, property advice and mortgage options, retirement projections and planning, investment education and debt management [13].

Billy Hensley, CEO of The National Endowment for Financial Education (NEFE), argues that it is pivotal employers offer a “personal finance ecosystem” [14].

“Single, tactical solutions cannot work by themselves,” he says. “If it was just about more money or more education, we would’ve solved the problem already.”

The ecosystem approach means that rather than adopting a blanket approach for all employees, employers take the time to consider each of their employees’ unique circumstances – their financial knowledge, cultural influences, socioeconomic status, mindset, overall physical health, where they live etc. – and then tailor the advice accordingly.

Speaking to the Irish Times, Stephen McCormack, senior director and head of financial planning at WTW, agrees. “It can be far more beneficial for employers to provide one-to-one advice sessions with an external adviser to allow employees to discuss their personal situation, confidentially, to get to the core of their financial distress,” he says [15].

“This will enable them to identify the issues, put a plan in place, specific to their needs and objectives, and monitor the progress on an ongoing basis.”

TIAA’s financial wellness survey from 2022 found that employees who have participated in an employer financial wellness programme are twice as likely to have a high financial-wellness rating than those who are not offered the resources or do not participate [16].

54% or participants of such programmes were confident they would retire when they want, compared to 32% of nonparticipants. While 50% of participants were confident they will not run out of money, compared to 29% of nonparticipants [17].

The benefits for employees, then, are stark. But employers, too, gain massively from ensuring their staff are financially literate.

Employer benefits

According to a 2018 Financial Health Network Survey, almost three-quarters of workers with high financial stress said it distracts them at work [18].

56% of employees who suffer distraction at work due to financial stress say they spend three or more work hours a week dealing with or thinking about issues related to their personal finances [19].

A TIAA Institute and the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center (GFLEC) report from 2023 found similar results, saying that employees spend an average of eight hours a week dealing with financial issues, with four of those hours occurring at work [20].

This level of stress and distraction costs employers money.

A 2023 study in the Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing found that a well-designed financial education programme can remove at least one hour per week of worry and financial distress for each employee who participates in that programme [21]. Assuming a minimum wage of $15 per hour, at a company with 30 minimum-wage employees, a good programme can recover at least $22,500 of value per year [22].

“Organisations have every reason to want their employees to be financially aware. A well designed employee financial wellness programme can help employers reduce a key barrier to productivity and motivation in the workplace,” says McCormack [23].

Not only does keeping employees financially literate eliminate a key distraction and increase staff productivity, but it aids massively with retention.

Only 54% of employees who are financially stressed feel there is a promising future for them at their employer, compared to 69% of employees who are not stressed about their finances. Financially stressed employees are also twice as likely to be looking for a new job as their unstressed colleagues (36% versus 18%). And 73% of financially stressed employees say they would be attracted to another employer that cares more about their financial well-being [24].

The aforementioned Financial Health Network Survey from 2018 found that 60% of people said they’d be more likely to stay at a job if their employer offered financial-wellness benefits [25]. Such initiatives shouldn’t be viewed as “charity” from an employer standpoint, says Annamaria Lusardi, a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) and founder and academic director of GFLEC. Instead, they should view it as a way to “retain and attract workers and make them more financially healthy and productive” [26].

Employers are often reluctant to engage in such initiatives because they’re viewing these programmes purely through the lens of taking cash out the tin. But the return on investment is clear. On average, employee benefits cost employers between 30–40% of the average worker’s base salary [27]. It’s worth investing the time and money to make sure that cost is contributing to your business.

Moving forward

Money is an awkward subject. The adopted wisdom is that it’s best not to talk about it. We inherit certain financial skills from our parents and just have to hope that we’re lucky enough that that will prove sufficient. But it’s not. Employers have an obligation to ensure their staff are financially literate. That means teaching them about key areas in which they can make improvements, such as budget and savings planning, financial goals, property advice, retirement projections, investment education and debt management – and tailoring that advice according to each individual’s circumstances. Not only is it the right thing to do, but it offers benefits to the employer in terms of staff productivity and garnering company loyalty.

The stigma around money is shifting. It’s time for employers to play their part in helping the pendulum swing.

More on Employer Benefits

Addressing High Housing Costs in Ireland: Strategies for Employers

How Much Should You be Working?

References

[7] https://hbr.org/2024/01/its-time-to-prioritize-employees-financial-health?ab=HP-hero-featured-text-1

[12] https://hbr.org/2024/01/its-time-to-prioritize-employees-financial-health?ab=HP-hero-featured-text-1

[14] https://hbr.org/2024/01/its-time-to-prioritize-employees-financial-health?ab=HP-hero-featured-text-1

[20] https://hbr.org/2024/01/its-time-to-prioritize-employees-financial-health?ab=HP-hero-featured-text-1

[21] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0278425423000212

[22] https://hbr.org/2024/01/its-time-to-prioritize-employees-financial-health?ab=HP-hero-featured-text-1

[26] https://hbr.org/2024/01/its-time-to-prioritize-employees-financial-health?ab=HP-hero-featured-text-1

[27] https://hbr.org/2024/01/its-time-to-prioritize-employees-financial-health?ab=HP-hero-featured-text-1

Introduction

January is not only a reset of the calendar. For many of us, it is a reset of our goals and ambitions. We look back on what we achieved in the past year, what we want to achieve this year, and enter a period of reflection.

We evaluate our progress – professionally, personally – and in a flurry of excitement and/or existential panic, commit ourselves to the task of betterment. We scribble down goals for the year ahead. We’re going to learn French, and maybe Spanish too. We’re going to lose not just that Christmas weight but a further stone on top of it. We’re going to get the promotion, travel to that beach paradise, eat healthier, take more photos, and just generally, finally become the rich/pretty/happy/smart/loved/well-read version of ourselves we were always meant to be.

Until after about three days of pursuing this idealised final form, we collapse in a heap and decide Netflix and a takeaway sounds like a better idea.

Like Icarus, we flew too close to the sun, got burned, and crashed back to Earth before the New Year’s hangover had even fully evacuated our system. Because the problem with “New year, new me” is it can only ever be half-true.

Which isn’t to say we shouldn’t pursue new goals – we can always strive for more. Rather that we should do so intelligently. Setting objectives is not just doable but recommended. It helps keep us on track, steadies our progress, and offers clarity and motivation.

There’s a story educators often cite that backs this up.

Many years ago, a survey was taken of students in their senior year at Yale University. Researchers asked the students if they had any goals for their future, and if any of them had written these goals down. 3% had. The rest, in much more relatable fashion, had not. Twenty years later, the researchers tracked down this same group of students and found that the 3% who had written down their goals had out-achieved their peers who hadn’t done so financially and professionally, while also being happier and more self-confident [1].

Now, does this story demonstrate the undeniable power of writing down one’s goals and prove that if you wish to be successful that there is a sure-fire way to do so? No, because the story is almost certainly untrue. A low-rent parable that gets wheeled out by educators all the same because, like all tales that pass into folklore, the heart of its lie speaks to an accepted truth: setting goals leads to progress.

While that specific story may be false, studies have shown that appropriate goal setting, along with timely and specific feedback, can lead to higher achievement, better performance, a high level of self-efficacy, and self-regulation [2]. And yet, when asked “Were you taught how to set goals in school?” 85% of individuals responded “no” [3].

In other words, we believe in the power of setting goals, we just have no idea how to do it.

The courage to want

Writing in Forbes, Life Performance Coach Julien Fortuit notes that, “Fear is probably the most common impediment to goal setting, even though many people may not admit it. Fear of failure – that you’ll set a goal, but not be able to achieve it, and suffer embarrassment, shame and disappointment in the process – underlies so much foot-dragging about setting and achieving goals” [4].

Fortuit acknowledges, too, that oftentimes we don’t just fear failure, but success. Applying for that new job, promotion etc. is often accompanied by a sudden spike of dread: What if I actually get this? Will I be able to do it? What will it mean for my life? What if I don’t like it? Is this the right move? It suddenly seems so much easier to put our dreams back in our pocket and settle for what we have.

Some people even fear speaking their goals out loud, or fear admitting to having any in the first place – they deny themselves the evaluation required to know what it is that they want. Fortuit writes that, “Many people are afraid of setting goals “just” for themselves. They fall into a common mental trap of believing that the desire for attainment or advancement is inherently narcissistic, and that settling and being content where you are is somehow ideal” [5].

All these impediments are self-created: fear of failure, of success, of daring to dream in the first place. And while feeling these things may be totally normal, allowing them to stop you from pursuing a goal is foolhardy.

So, before setting out toward your goal, first examine yourself and decide what it is you really want – to work in a new sphere? A new country? To earn more money? To start your own business? Once you’ve taken the requisite time to self-analyse and understand where it is you want to be, only then can you take the first steps to getting there.

Enacting objectives

Regardless of the goal, the consensus is that if you wish to achieve it, you must make it SMART. Smart goals are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound.

Specificity is crucial. “I want to be a better employee” means nothing. “I want my sales record this year to improve by 15% compared with last year” is SMART. It is one clear objective, with a measurable area of improvement, a challenging but achievable target and a clear timeframe.

The primary issues that hold back goals are that the end desire is either too vague or too ambitious. Give yourself something tangible to focus on achieving – it doesn’t have to be an outcome, like the 15% example, rather a process. Say you want to spend 10 minutes a day studying a language rather than saying “I want to be fluent in Korean”, or “I want to run twice a week” rather than “I want to do a marathon.”

For goals that take place over a long period of time, it can be a good idea to set smaller objectives in between so that you can keep yourself on track. For example, if you want to read 30 books this year, it can be all too easy to fall behind early while convincing yourself that things will improve later in the year – that future you will pick up the slack. Except inevitably, as the first firework of December 31st fizzes into the sky, future you is left remonstrating past you for putting them under so much pressure and forcing them to end the year feeling like a failure.

A better approach would be to measure your progress by ensuring you’ve read ten by the end of April, twenty by the end of August etc. Not only does this make the goal more measurable and less daunting, but you get bursts of satisfaction through the year every time you see you’re on track.

Worth trying, too, is making your resolutions public. You will feel – rightly or wrongly – a level of scrutiny as to your progress. It is only human nature. Of course none of us want to feel like failures. But far more terrifying is the prospect of everyone else seeing us as one.

Additionally, ensure that you’ve connected a “why” to each of your ambitions. If our brain is able to link the efforts required to achieve this goal with a tangible, meaningful reward in the future, it is more likely to find the necessary motivation when things get tough. Wanting to hit sales targets so you can earn commission is fine. Wanting to hit sales targets so you can earn commission that you’re putting towards a deposit for a house for your family is better. Of course, it need not be so primal. Wanting to buy those new shoes, to feel more confident, to renew your season ticket or shop at the posh supermarket – whatever motivates you.

The benefits aren’t just in achieving goals but also in what having goals does to our psyche. A study amongst pulpwood producers in the southern United States showed that not only did productivity improve drastically amongst workers once goals were introduced, but that “within the week, employee attendance soared relative to attendance in those crews who were [not set goals]. Why? Because the psychological outcomes of setting and attaining high goals include enhanced task interest, pride in performance, a heightened sense of personal effectiveness, and, in most cases, many practical life benefits such as better jobs and higher pay” [7].

Habits

If you want to make long-term improvements, make habits your best friend.

James Clear’s Atomic Habits is the obvious guide for bringing habits into your life. He shows how micro-changes – getting 1% better every day – make all the difference. Habits take time to form, and there’s no shortcut to making them stick. It takes consistency, showing up every day. In order to do that, Clear suggests starting with a habit that is small and attainable. If you set yourself the target of running 10k three times a week, you may have a great first day, a great first week even, but sooner or later you’re going to struggle to keep it up (unless you’re built like The Hardest Geezer, in which case good for you). Clear’s advice for exercise isn’t about setting targets for runs or lifts, it’s about laying out your gym clothes before you go to bed or leaving your gym bag by the door. Truly the little things.

Writing in Harvard Business Review, Sabina Nawaz, a global CEO coach for a number of Fortune 500 corporations, says the same. “It usually takes my workshop participants between three and eight tries before they come up with something sufficiently small enough to be considered a micro habit.”

“When I tell them reading for an hour each night is too large, they then change to reading for 45 minutes, then 30 minutes, and so on. Finally, I tell them, “You will know you’ve truly reached the level of a micro habit, when you say, ‘That’s so ridiculously small, it’s not worth doing’”” [8].

It may sound ridiculous, condescending even, to say “start reading one page a night” or “start doing one pushup a day”, but building consistency is far more important than having an impressive week or month then falling off the wagon. That may mean sticking with your teeny-tiny habit longer than you’d like to, even if you think you’re capable of more. “You’ve stuck with your original micro habit long enough when you feel bored with it for at least two weeks in a row,” Nawaz says. “Then increase it only by about 10%.”

Effective goals

Every year, all over the world, people set themselves goals they have no chance of achieving. It’s a double negative – not only are they not fulfilling the goal, but they’re left feeling like failures because they fell short. To make effective goals, one must first self-evaluate and decide what you really want. You have to know where you’re going before figuring out how to get there. Once you’re set on the destination, in order to make your goals achievable, make sure they’re SMART, making use of habits, linked to a clear “why”, and focused on processes rather than just outcomes.

Resolutions don’t have to be distant dreams we’ll never achieve; they can be powerful motivators that set us on the path to success. So put last year’s missed targets behind you and set yourself goals you can actually reach and truly want to.

More on Goal Setting

How to Achieve Peak Performance

New Year’s Resolutions: How to Make Them Useful

More on Habits

Why Achievement Doesn’t Guarantee Happiness

Boosting personal and organisational performance in the digital age (Podcast)

References

[2] https://www.jstor.org/stable/41684067?read-now=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[3] https://www.jstor.org/stable/41684067?read-now=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[6] https://www.jstor.org/stable/4166132?read-now=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[7] https://hbr.org/2020/01/to-achieve-big-goals-start-with-small-habits

[8] https://hbr.org/2020/01/to-achieve-big-goals-start-with-small-habits

Introduction

Survivorship bias is a subtle yet pervasive cognitive oversight that significantly impacts our understanding of success and failure. Often going unnoticed, it affects various areas, from entrepreneurial ventures and the entertainment industry to our everyday decisions and scientific research methodologies.

This bias emerges from an emphasis on the winners—those who have surmounted the odds—while inadvertently neglecting those who did not achieve the same success. Success stories are highlighted and celebrated, leading to a skewed perception that such outcomes are more common than they are. Conversely, the experiences of those who fail are frequently overlooked, leaving a gap in the narrative of what truly contributes to achievement or failure.

In business, for instance, we hear about the few start-ups that evolve into tech giants but seldom about the many that don’t survive their early years. The spotlight shines on celebrities and star performers in entertainment while numerous struggling artists remain unseen. This selective visibility can mislead aspiring individuals about the realities and challenges of success.

Recognising survivorship bias is crucial for a more accurate and balanced understanding of the factors leading to success. It encourages a comprehensive analysis of both successful and unsuccessful cases, promoting a more realistic approach to the probabilities and potential outcomes in any field.

Survivorship Bias: The Hidden Half of Success Stories

Survivorship bias casts a long shadow over our collective narrative, favouring stories of victory. The media celebrates tales of success, featuring business leaders, cultural icons, and renowned authors. This prominence of success stories overshadows the numerous trials and errors that either lead to victory or result in obscurity. Such selective storytelling creates a skewed reality where only victors command attention, while the majority who don’t reach such heights are forgotten.

In technological innovation, for example, the few smartphone models that dominate the market and public consciousness overshadow the numerous attempts that failed to find a market or fell short on functionality. We frequently celebrate the end products of innovation, from ground-breaking apps to transformative gadgets, while neglecting the graveyard of ideas and prototypes that did not survive the market’s rigours.

In sports, every champion on a podium represents the peak of a vast pyramid of athletes who trained with fervour and dedication but did not reach the summit of elite recognition. The winners’ spotlight often ignores the dedication and sacrifice of those who compete valiantly yet do not secure the medals and accolades.

In “Fooled By Randomness,” Nassim Nicholas Taleb illustrates how our understanding is limited by what we see, causing us to neglect the fuller picture that includes the ‘invisible’ majority contributing to the narrative of progress and competition without acknowledgement. In science, for every celebrated discovery published in journals, there are numerous unreported experiments and hypotheses that were essential stepping stones despite not achieving the desired result. These instances are critical to advancing knowledge, yet they remain unrecognised.

These examples give us a clearer picture of survivorship bias and its pervasive impact across various sectors. They remind us that what is celebrated and visible is just the tip of the iceberg, with much remaining unseen beneath the surface of success.